Coinfection of hepatitis A virus genotype IA and IIIA complicated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia, prolonged cholestasis, and false-positive immunoglobulin M anti-hepatitis E virus: a case report

Article information

Abstract

A 37-year-old male presented with fever and jaundice was diagnosed as hepatitis A complicated with progressive cholestasis and severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia. He was treated with high-dose prednisolone (1.5 mg/kg), and eventually recovered. His initial serum contained genotype IA hepatitis A virus (HAV), which was subsequently replaced by genotype IIIA HAV. Moreover, at the time of development of hemolytic anemia, he became positive for immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-hepatitis E virus (HEV). We detected HAV antigens in the liver biopsy specimen, while we detected neither HEV antigen in the liver nor HEV RNA in his serum. This is the first report of hepatitis A coinfected with two different genotypes manifesting with autoimmune hemolytic anemia, prolonged cholestasis, and false-positive IgM anti-HEV.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) remains an important causative agent of acute viral hepatitis, causing large outbreak or severe cases of fulminant hepatitis with fatal outcomes. Acute hepatitis A can be complicated by extrahepatic manifestations, including hemolytic anemia, aplastic anemia, acute renal failure, and acute reactive arthritis.1,2

Although HAV displays only a single serotype, seven HAV genotypes have been identified: four genotypes (I, II, III and VII) are of human origin, and other three (IV, V, VI) are of simian origin. HAV genotypes have unique geographic distributions; however, co-circulation of multiple genotypes or subgenotypes has been reported in some regions of world.3

This report presents a peculiar coinfection hepatitis with the HAV genotype IA and IIIA, complicated by severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia and prolonged cholestasis, along with coexistence of IgM anti-hepatitis E virus (HEV). We performed immunohistochemical staining of HAV antigen and HEV antigen in the liver biopsy specimen, and molecular detection of HAV RNA and HEV RNA in the serial serum samples obtained from the patient.

CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old male visited the emergency room on December 28, 2008 for treatment of fever (40℃), chills, and jaundice lasting for 2 days. He was a nonsmoking social drinker, and denied recent overseas travel, contact with hepatitis cases, or taking any medications. His past medical history revealed an episode of pneumonia and bronchiectasis that occurred 20 years earlier. Physical examination showed a temperature of 40℃ and mild icterus without hepatosplenomegly. Results from chest and throat examination were normal without cervical lymphadenopathy. His initial level of aspartate transaminase (AST) was 12,000 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 8,129 IU/L, total bilirubin 4.5 mg/dL, prothrombin time 23.6 second (international normalized ratio 2.06) and hemoglobin (Hb) 14.3 g/dL. IgM anti-HAV (Microparticle Enzyme immunoassay, Abbott, Wiesbaden, Germany) and IgG anti-HAV (Radio-immunoassay kit, General Biologicals corp., Taiwan) were both positive. Hepatitis B virus surface antigen, IgM anti-HBc, hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA, and anti-HCV were all negative. IgM anti-HEV (Genelabs Diganostics, Singapore) was negative. Chest X ray and CT scan of the abdomen and chest showed no remarkable findings. Under diagnosis of acute hepatitis A, the patient received supportive care showing gradual recovery, and AST/ALT levels decreased to 285/919 IU/L, with a stable hemoglobin level of 14.4 g/dL, while his total bilirubin level progressively increased up to 21.8 mg/dL at hospital discharge (January 6, 2009) suggesting a prolonged cholestatic feature.

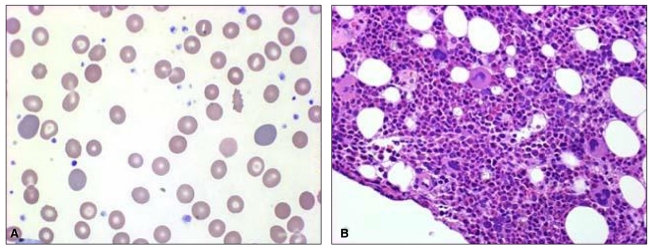

On January 12, 2009, he was readmitted for recurrent fever, general weakness, and aggravated jaundice. At this time, IgM anti-HEV was positive with persistently positive IgM anti-HAV. Total and direct bilirubin levels were 39 mg/dL and 29 mg/dL, respectively, with an alkaline phosphatase level of 374 IU/L, and Hb level was 13.4 g/dL. Until January 24, total bilirubin level increased rapidly, up to 64.1 mg/dL (direct bilirubin level of 41 mg/dL), and Hb level fell rapidly to 5.5 g/dL, despite decreasing levels of transaminase. Serial laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. Haptoglobin level was 27.3 mg/dL and direct Coombs' test was positive (anti-IgG type) with polychromasia and anisocytosis on a blood film (Fig. 1A), which was compatible with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). IgM anti-parvovirus B19 was negative.

(A) Peripheral blood smear showing marked polychromasia and anisocytosis (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×1,000). (B) Photomicrographs of a bone marrow biopsy section showing increased erythropoiesis [hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E), ×400].

Oral prednisolone therapy (1 mg/kg) was started on January 22, however, his reticulocyte count remained low (0.13%), and he received 17 units of red blood cell transfusion for 11 days. To exclude the possibility of pure red cell aplasia, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were performed, and it showed increased erythropoiesis compatible with AIHA without evidence of pure red cell aplasia (Fig. 1B). The dosage of oral prednisolone therapy was incremented to 1.5 mg/kg/day, and after 8 days of the incremental dose therapy, the patient became gradually transfusion-independent with increase of Hb level to 12.1 g/dL. Liver function tests showed AST of 22 IU/L, ALT 136 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 285 IU/L, gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) 897 IU/L, and total bilirubin of 5.4 mg/dL.

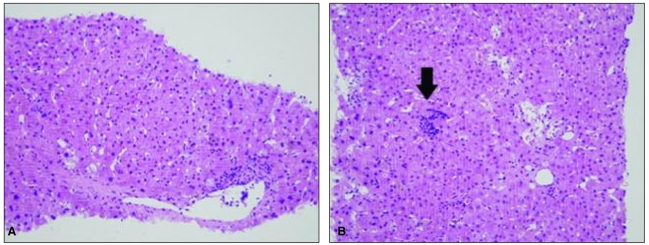

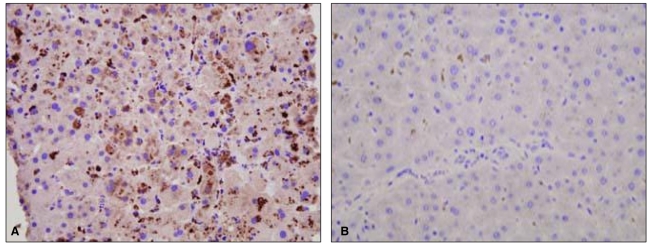

To exclude the possibility of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis associated with immunosuppressive therapy, percutaneous liver biopsy was undertaken on February 12, which revealed hepatocellular and canalicular cholestasis, hepatocyte ballooning, and lobular spotty necrosis compatible with cholestatic hepatitis and extramedullary hematopoiesis (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical staining was performed for detection of HAV antigens and HEV antigens using HAV antibody (Purified HAV, Abcam, Cambridge, UK; mouse monoclonal, 1:50) and HEV antibody (Abbiotec, CA, USA; 1:200), respectively. Strong cytoplasmic staining for HAV was noted, whereas staining was absent in specimens used for negative control (Fig. 3). In this case, there was no staining for HEV antigen (data not shown).

The liver biopsy specimen exhibited hepatocellular and canalicular cholestasis, hepatocyte ballooning, and lobular spotty necrosis, consistent with cholestatic hepatitis. Extramedullary hematopoiesis was also seen (arrow; H&E, ×200).

Immunohistochemical staining of the liver biopsy specimen. Strong cytoplasmic staining for hepatitis A virus antigen was noted in our case (A), whereas staining was absent in a case of chronic hepatitis B (B) as a negative control (A and B, ×400).

After a 2 month-period of gradual tapering of prednisolone, complete recovery of liver function was achieved at 5 months after the patient's initial admission. However, his IgM anti-HAV was positive until May 29, while both IgM anti-HEV and IgG anti-HEV (Genelabs Diganostics, Singapore) were negative.

During the course of his illness, serial serum samples were available for detection of HAV RNA and HEV RNA, according to the method described in previous studies.4 All HAV RNA-positive samples were sequenced using the BigDye Terminator (ABI Prism 377 automatic sequencer, Toroed, Norway). Interestingly, initial HAV detected on January 14, 2009 was genotype IA, which was subsequently replaced by HAV genotype IIIA during the later phase of the illness (April 22, 2009), while HEV RNA was not detected by Okamoto's method, as previously reported.5,6

DISCUSSION

This report described a case of acute viral hepatitis coinfected by HAV genotype IA and genotype IIIA complicated with severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia, prolonged cholestasis, and coexistence of IgM anti-HEV, which was successfully treated by high dose (1.5 mg/kg/day) prednisolone therapy.

There have been a few reports of severe Coombs-positive AIHA with or without pure red cell aplasia, complicating acute viral hepatitis.7 However, coinfection of HAV genotype IA and IIIA complicated with severe AIHA has not been reported. Genotype 1A HAV was a major genotype in Korea, however, during recent nationwide outbreak of hepatitis A, a rapid genotypic shift from genotype IA to IIIA has occurred.4,8 Therefore, at least two genotypes of HAV co-circulate in Korea.

Coinfection of the HAV genotype IA and IIIA was a peculiar finding in this case. From onset of symptoms to development of AIHA, HAV genotype IA was consistently detected in the patient's plasma and stool. Subsequently, during prolonged follow-up, his HAV genotype was replaced from genotype IA to IIIA. This replacement can be explained by initially mixed infection of HAV genotype IA and IIIA with a dominant population of HAV genotype IA and reciprocal inhibition of genotype IIIA. During his initial hepatitis course, vigorous immune responses may have controlled HAV genotype IA up to an undetectable level, and subsequent strong immunosuppression for the treatment of hemolytic anemia may support replication of HAV genotype IIIA, a minor population. To our knowledge, this is the first case of coinfection of hepatitis A genotype IA and IIIA documented. Coppola et al9 reported a case of acute hepatitis A complicated with prolonged cholestasis and coinfection of genotype IA and IB, and suggested that coinfection of two HAV subgenotypes may be a reason for prolonged cholestasis and viremia due to impairment of antibody production or neutralizing activity on the basis of the simultaneous antigenic stimulatory effect of the two HAV isolates. However, HAV has only one common serotype, and this finding was not supported by experimental data.

The interesting finding of this case was that IgM anti-HEV at the first manifestation was negative, which turned out to be positive at the initiation of hemolytic anemia. Afterwards, the transiently positive result for IgM anti-HEV turned out to be negative, along with a negative result for IgG anti-HEV during the follow-up period. Both hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis E virus (HEV) infection can be transmitted by the fecal-oral route with similar incubation periods and clinical presentations. Among patients with sporadic acute viral hepatitis, cases showing simultaneously positive results for immunoglobulin M (IgM) anti-HAV and IgM anti-HEV have been reported, and were regarded as coinfection of HAV and HEV.10,11 However, HEV RNA was not detected in serum and stool samples, while HAV RNA was detected and genotyped. In immunohistochemical staining of liver biopsy specimens, HAV antigens showed strongly positive staining, in contrast to no staining for HEV antigens, although we were not able to obtain adequate positive control specimens. All of these results suggested the false positive reaction of initially positive IgM anti-HEV, rather than a true coinfection of HEV along with HAV.12 Severe cell necrosis associated with HAV infection may induce autoimmune reaction such as hemolytic anemia or autoimmune hepatitis.13,14 Nonspecific induction of IgM anti-HEV during massive hepatic necrosis death in the hepatitis phase of this case may be a possibility.

In conclusion, severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia and prolonged cholestasis can be complicated with acute hepatitis co-infected by HAV genotype IA and IIIA, which was successfully treated with high-dose prednisolone therapy. The coexistence of IgM anti-HEV in the setting of hepatitis A seems to be a false positive reaction rather than a true coinfection.

Abbreviations

AIHA

autoimmune hemolytic anemia

anti-IgG

immunoglobulin G antibody

ALT

alanine aminotransferase

AST

aspartate aminotransferase

HAV

Hepatitis A virus

Hb

hemoglobin

HCV

Hepatitis C virus

HEV

Hepatitis E virus

HAV RNA

hepatitis A virus ribonucleic acid

HEV RNA

hepatitis E virus ribonucleic acid

IgM anti-HAV

immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis A virus

IgM anti-HBc

immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis B core antigen

IgM anti-HEV

immunoglobulin M antibody to hepatitis E virus

INR

international normalized ratio

γ-GT

gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase