INTRODUCTION

Primary liver cancer is the sixth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [

1,

2]. In 2020, the highest age-standardized incidence rates (ASRs) of liver cancer were observed in Eastern Asia (17.8/100,000 person-years), Northern Africa (15.2/100,000 person-years), South-Eastern Asia (13.7 /100,000 person-years), and South Korea (14.3 cases/100,000 person-years) [

1]. In South Korea, liver cancer ranked second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer-related deaths in 2016 [

3]. As liver cancer has the highest mortality rate in middle-aged Koreans (i.e., individuals aged 40ŌĆō59 years) having the highest socioeconomic productivity, there is a substantial disease burden associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Therefore, efforts have been continued to accurately investigate the incidence of liver cancer and to establish proper strategies to reduce liver cancer accordingly.

The incidence of liver cancer has been extensively investigated worldwide, but the incidence of HCC is relatively unknown. HCC is the most common primary liver cancer, comprising 75ŌĆō85% of all primary liver cancers. Most previous studies reported the incidence of all types of cancers in the liver (e.g., intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, hepatoblastoma), and thus did not discuss exclusive data about HCC [

1,

4-

6]. In addition, the main source of data for previous epidemiologic studies on HCC in Korea was the Korean Primary Liver Cancer Registry [

7-

10]. Although the data from this registry are representative of patients with HCC nationwide, the registry does not include all patients with HCC.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and liver cirrhosis are risk factors for HCC. In a cohort study concerning the Korean population conducted from 2003ŌĆō2005, the most frequently identified etiologies of HCC were HBV (62.2%), HCV (10.4%), and alcohol or an unknown etiology (27.4%) [

11]. During the past several decades, many efforts have been made to eradicate HBV, the main cause of HCC. A national project has been in place since 1995 to vaccinate young people against HBV, and patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) have been eligible to receive reimbursement for the cost of lifelong antiviral treatment since 2010 [

12]. As a result, HBV infection has decreased dramatically from 8% in the 1990s to 3% in the 2010s in Korea [

12]. However, at the same time, there is an increasing incidence of HCC caused by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) because of recent westernization of the dietary pattern in Korea [

13,

14]. The improved control of viral hepatitis and increased prevalence of metabolic liver diseases suggest that the etiology of HCC may be changing.

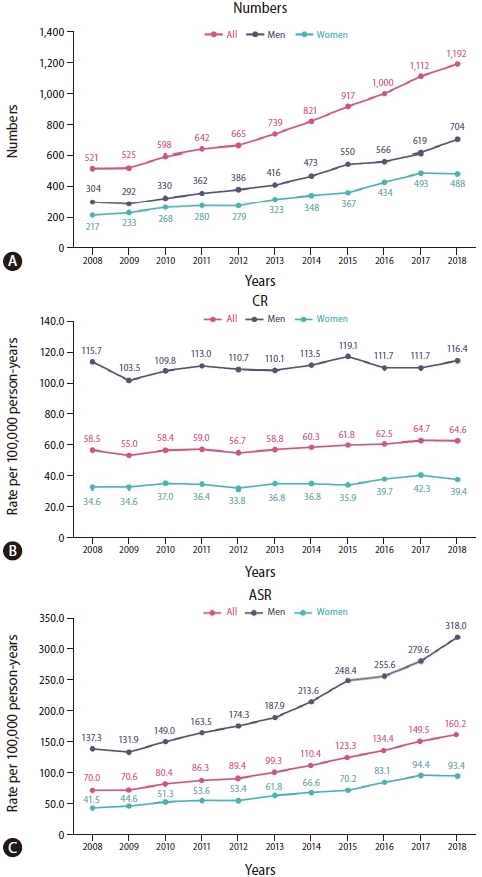

Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively analyze trends in HCC incidence and the factors that affect these trends. We aimed to analyze the trends in the incidence rates of HCC over 10 years (2008ŌĆō2018) and to predict the incidence rate of HCC in Korea for the year 2028. In addition, we aimed to study serial changes in the incidence of HCC according to age groups, economic classes, and etiologies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This retrospective cohort study used data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (KNHIS) database. Data were extracted and coded with an encrypted number, in accordance with the institutional disclosure principle after permission had been obtained from the National Health Corporation. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hanyang University, Seoul, Republic of Korea (2019-07-014).

Database characteristics

The Korean government created universal health insurance systems in 1989 and consolidated them into a single system in 2000 [

15]. The health insurance system is mandatory for all Korean citizens, and 97.2% of the Korean population has been enrolled in the system since 2018. Data are entered into the KNHIS database when Korean clinics or hospitals submit an insurance claim to the National Health Corporation for their medical services to be reimbursed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included patients from the KNHIS database who had been newly diagnosed with HCC (C220 and V193) between January 2008 and December 2018. We excluded patients if any of the following conditions were met: 1) diagnosis with HCC between 2005 and 2006 due to the low reliability of the data from that period; 2) diagnosis with HCC in the 2 years prior to index date; 3) diagnosis with malignancies other than HCC (C codes other than C220 and V193); 4) history of organ transplantation; 5) human immunodeficiency virus infection; or 6) missing patient identification information (age or sex).

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoints of this study were the change in the incidence rate of HCC over the past 10 years (2008ŌĆō2018) by age groups and the predicted incidence rate of HCC in Korea for 2028. The secondary endpoints were the changes in the HCC incidence rate according to age groups, economic classes, and etiologies of HCC.

Stratification

Patients were divided into four age groups: 0ŌĆō29 years, 30ŌĆō59 years, 60ŌĆō79 years, and Ōēź80 years. The economic classes of the study participants were determined by the premiums of their medical insurance. Medical insurance groups were classified into 20 categories (Q1 to Q20) based on their insurance premiums. The Medicare group was excluded from these categories because patients in this group were exempted from paying the insurance premiums. The 20 categories were grouped into Q1ŌĆō5, Q6ŌĆō10, Q11ŌĆō15, and Q16ŌĆō20. Patients in the Q16ŌĆō20 group paid the highest premium, and patients in the Q1ŌĆō5 group paid the lowest premium.

Definition of HCC

The operational definition of HCC included patients who had assigned both the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code of C220 and the rare incurable disease code of V193 (cancer). If a patient is diagnosed with a cancer and assigned the V193 code, the patient only pays 5% to 10% of the total medical expenses. Cancer patients covered 10% of the total cost in 2008 and 2009; the proportion decreased to 5% in December 2009. Therefore, the KNHIS requests more information at the time of HCC diagnosis, and these patients are strictly monitored by the government. The KNHIS reviewed whether HCC was diagnosed based on histology, dynamic computed tomography, and/or magnetic resonance imaging findings. The imaging findings suggestive of HCC included a liver nodule >1 cm, arterial hypervascularity of the nodule, and washout in the portal venous or delayed phase [

16].

Identification of etiologies and comorbid conditions of HCC

Etiologic diseases (CHB, chronic hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease, and NALFD) were identified if the code for the disease or prescription of its treatment was assigned in the calendar year containing the index date or within one calendar year before or after this year (3 years). When two or more etiologic factors were present, patients were classified into the class for the higher-ranked condition in the following order: HBV, HCV, alcoholic liver disease, NAFLD, and others. We have added this information to the Methods section. Comorbid conditions (liver cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, other malignancies, cardiovascular diseases, and cerebrovascular diseases) were identified if the relevant ICD codes were assigned twice during the calendar year containing the index date or within one calendar year before or after this year (3 years). Each definition and the relevant ICD codes were depicted in

Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the median (interquartile range) or frequencies with percentages, as appropriate. The 2005 Korean population covered by the KNHIS was used as the standard population for calculation of the ASR. To evaluate trends in the incidence of HCC during the past 10 years, we used the joinpoint regression method to calculate the average annual percent change (AAPC) in incidence rates. We used the Poisson regression model to predict the incidence of HCC. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and R software (version 3.6.0; http://cran.r-project.org/). Two-sided P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

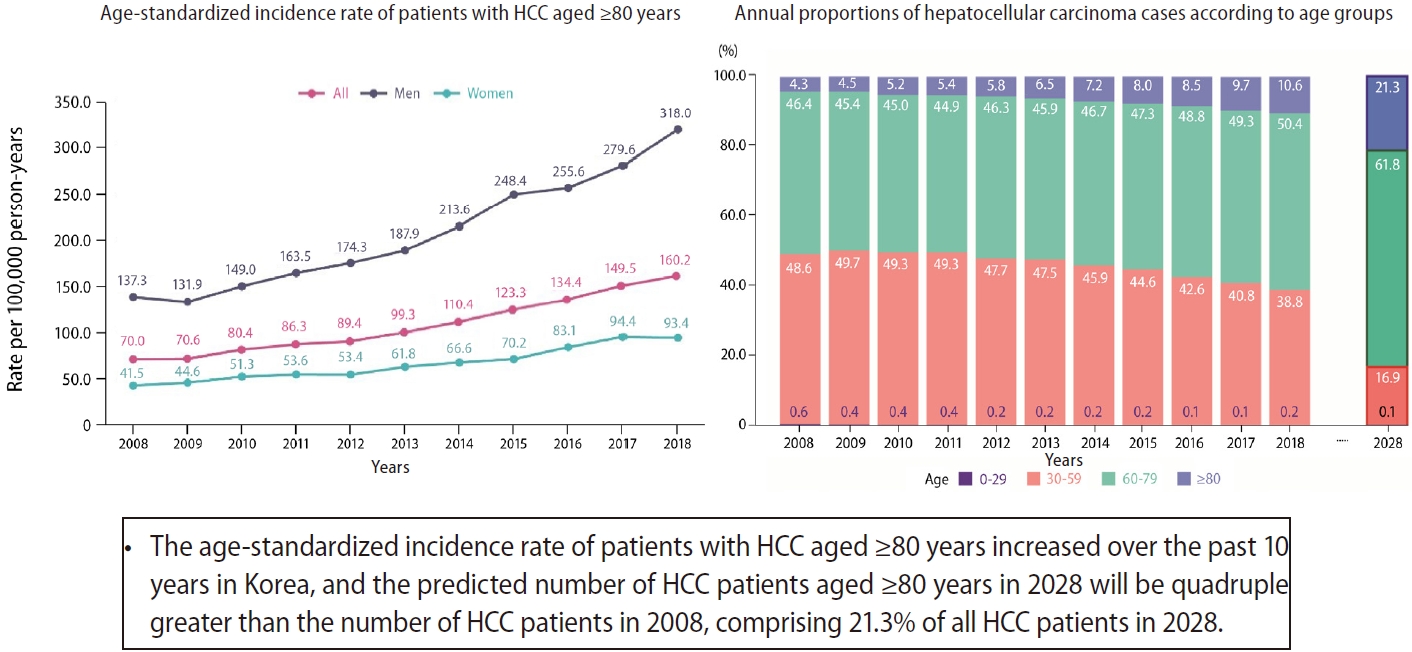

From 2008 to 2018, the numbers and ASRs of HCC significantly decreased. However, in patients aged Ōēź80 years, the ASR significantly increased by 0.96% per year; the CR of HCC also increased. By 2028, despite the estimated decrease in HCC incidence in the entire population, the incidence and the proportion of HCC patients aged Ōēź80 years are estimated to increase. To our knowledge, this study is the first to include a large number of patients (n=127,426) from the KNHIS database, which includes most Korean citizens. The inclusion of such a large number of patients has enabled a comprehensive analysis of the longitudinal trends in HCC incidence in Korea. The estimation of the current and future incidences of HCC in different age groups is important for performing an economic evaluation of the burden of HCC and for formulating an appropriate healthcare policy to control HCC.

There are several important clinical implications of this study. First, the decreasing trend in the ASR of HCC incidence in Korea is similar to the trends observed in Asians living in other countries. A recent study by Petrick et al. [

17] estimated the current and future incidences of HCC in the United States. The overall ASR of HCC increased from 2000 to 2012, and the researchers predicted that it would further increase from 2013 to 2030. In contrast, the ASR of HCC in Asians is expected to decrease from 2013 to 2030 by an average of -1.8% each year, and the ASR of HCC in 2030 is estimated to be 15.5 per 100,000 person-years. Another study from the United States reported that the ASR of HCC significantly decreased from 2007 to 2016 at a rate of -2.72% per year in patients with Asian/Pacific islander ethnicity [

18]. Similar to these two studies, the annual decrease in ASR in our study was -3.9% from 2008 to 2018, and the predicted ASR in 2028 is 9.7% per 100,000 person-years. The projected decrease in the ASR and number of patients with HCC in Korea may be a result of better control of HBV and HBV-related HCC. Although HBV remained the strongest contributing factor to HCC in 2018, the total number of patients with HCC and the proportion of cases of HBV-related HCC decreased annually from 2011 to 2018. Nationwide efforts have been made to eradicate HBV, the main cause of HCC. HBV vaccination has been a component of the national vaccination program since 1995; more than 95% of infants are currently vaccinated, which has contributed to a low positivity rate (0.2%) for hepatitis B surface antigen in children [

19]. In addition, the introduction and expansion of insurance coverage of antiviral agents for HBV have improved the control of HBV replication and prevented cirrhosis-related complications and HCC [

20].

Second, the HCC incidence trends varied noticeably among age groups. While the absolute number of HCC cases in patients aged 0ŌĆō29 years was very few, the annual decrease in the ASR was the greatest in this age group (AAPC, -13.59%), and the incidence is predicted to approach zero by 2028. From 2008 to 2018, the ASR decreased in patients aged 30ŌĆō 59 years, and it did not change in patients aged 60ŌĆō79 years. The ASR anticipated to decrease to 15.5/100,000 person-years in patients aged 30ŌĆō59 years, whereas it is predicted to increase by 103.2 person-years in patients aged 60ŌĆō79 years by 2028. Despite a gradual decrease in the ASR over time, the socioeconomic burden of HCC is expected to increase because of increasing life expectancy and a greater likelihood of HCC with increasing age in patients with chronic liver disease. Therefore, efforts should be made to control the HCC incidence in middle-aged patients with the highest socioeconomic productivity to alleviate the socioeconomic burden.

Third, it is concerning that the ASR of HCC is not declining in patients receiving Medicare. From 2008 to 2018, the ASR significantly decreased in all medical insurance groups, except the Medicare group. Conversely, there was a slight increase in the ASR from 2012 to 2018 in the Medicare group, although this difference was not statistically significant. It is unclear whether economic class directly affects HCC incidence. In a study by Anyiwe et al. [

21], patients in the lower income groups had an increased risk of HCC compared with those in the highest income group, despite adjustments for age, sex, and area of residence. Although economic class itself was not a risk factor for HCC, many risk factors for HCC were closely related to economic class. In our study, we did not find any differences in HCC etiology among medical insurance groups (

Supplementary Table 4). However, between 2008 and 2018, patients with HBV-related HCC in the Medicare group had significantly less use of antiviral treatment, than patients in the group with the highest medical insurance (Q16ŌĆō20) (

Supplementary Table 5). Further research is needed to confirm whether the reduced use of antiviral drugs in HBV-infected patients in the Medicare group is linked to uncontrolled viremia and thus affects HCC development.

Fourth, the proportions of patients developing HCC due to HBV and HCV still remained high in 2018, while the proportions of patients with HCC induced by NAFLD and alcoholic liver disease are increasing. In 2016, the World Health Organization set a goal of eliminating HBV and HCV by the year 2030 using prevention and treatment targets that aim to reduce annual deaths by 65%, increase the proportion of treated patients to 80%, and save 7.1 million lives globally [

22]. Consistent with this 2030 eradication strategy, vaccination against HBV and antiviral treatment for HBV and HCV will further reduce the incidence of HCC. However, the proportion of patients with NAFLD-related HCC increased by 2.7% annually in our study. NAFLD is the fastest growing cause of HCC in the United States and United Kingdom [

23,

24]. The prevalence of NAFLD-related HCC is likely to increase concomitantly with the increasing incidence of obesity. Therefore, management of metabolic indices through lifestyle modification is important for reducing the risk of HCC.

Finally, special attention is needed for patients with HCC aged Ōēź80 years. The absolute number, CR, and ASR of HCC in patients aged Ōēź80 years has significantly increased from 2008 to 2018, and the incidence is expected to continue increasing until 2028. An increasing trend in the ASR in the elderly population was also identified in a Taiwanese cohort [

25], and the most plausible explanation was that old age is a risk factor for HCC. The increasing incidence of HCC in older age groups is similar to that seen in other cancers. According to annual statistics from the Korean Central Cancer Registry, the proportion patients with gastric cancer aged Ōēź80 years was 7.5% and 12.7% in 2008 and 2018, respectively. The proportion patients with colon cancer aged Ōēź80 years was 9.4% in 2008 and 19.0% in 2018. Moreover, elderly patients have many comorbid conditions, such as liver cirrhosis or diabetes mellitus, which may further increase the risk of HCC. In our subgroup analysis of patients with HBV-related HCC, patients aged Ōēź80 years received significantly less antiviral treatment between 2008 and 2018 than did patients in other age groups (

P<0.001; data not shown). HBV is the most common etiology of HCC; therefore, uncontrolled HBV viremia in elderly patients can be associated with a greater incidence of HCC. This assumption requires subsequent verification in future studies. By 2028, the proportion of patients with HCC aged Ōēź80 years will increase to 21.3% of all patients with HCC. This is consistent with the report by Kim and Park [

4] that the age distribution of HCC in Korea has shifted towards the right between 2005 and 2014. When we look up the age structure of general population, the number of Koreans aged 80 years or older increased from 2008 to 2018 (number, 890,000 in 2008 to 1,845,000 in 2018; the proportion, 1.8% in 2008 to 3.1% in 2018) [

26]. Therefore, even considering that Korea is becoming an aging society, the proportion of HCC patients aged 80 years or older increased at a faster rate (4.3% in 2008 to 10.6% in 2018). Elderly patients with HCC often have additional comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and renal failure; thus, they may not receive adequate treatment because healthcare professionals are concerned about the abilities of these patients to tolerate standard HCC treatment. Conversely, using standard treatment for HCC without considering the frailty of these patients may cause toxicity or fatality. Therefore, guidelines should be formulated for customized management of elderly patients with HCC to improve the treatment and reduce the socioeconomic burden of HCC.

There were several limitations in our study. First, although we included the entire dataset from the KNHIS database in our analysis, the HCC incidence may have been underestimated because some patients with HCC may not have visited any hospital or the disease codes may have been missed. Second, we could not confirm the medical records of included patients from the hospitals; thus, there was a possibility of misclassification or under-/overestimation of HCC, etiologies of HCC, or comorbid conditions. Third, the operational definition of NAFLD-related HCC was somewhat liberal because we included patients with diabetes mellitus and without any other chronic liver diseases. However, NAFLD-related HCC accounted for only 10% of all HCC cases in our study, and this proportion was similar to a previous Korean study about the etiological distribution of HCC [

13]. Fourth, since we could not perform analysis by birth cohort, it was difficult to determine the exact timing of HCC reduction affected by expansion of HBV vaccination or antiviral treatment for HBV and HCV. Finally, prediction of future incidence assumes that past trends will continue; predictions may be inaccurate if there are various changes in the medical environment.

In conclusion, the ASR of HCC in Korea gradually declined over the past 10 years. However, the number, CR, and ASR of HCC are increasing in patients aged Ōēź80 years. In 2028, the number of HCC patients aged Ōēź80 years will be quadruple greater than the number of HCC patients in 2008, and 21.3% of all patients with HCC will be in this age group. A customized HCC management plan that considers the age and general health status of these patients is necessary. In addition, a national health strategy should be implemented to manage the economic burden of HCC.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement1

Supplement1 Print

Print