INTRODUCTION

Variceal bleeding and hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) in advanced liver disease are its serious and life-threatening complications. Vasopressin was used as a vasoconstrictor to treat variceal bleeding and HRS in the initial period. Although vasopressin was reported to have a moderate success rate, it has been associated with an unacceptable rate of ischemic adverse effects.1 Thus, terlipressin (triglycyl lysine vasopressin, Glypressin®) with its potency and prolonged duration of action was developed and introduced in early 1990s as an arginin vasopressin analogue. Although terlipressin has also some adverse effects such as paleness, arrhythmia, abdominal pain, hypertension and headache, the incidence rate of adverse events is very low.2-4

The severe and life-threatening complications after terlipressin therapy appear to result from tissue ischemia. Herein, we report a case where a 71-year-old male with alcoholic liver cirrhosis was diagnosed as peripheral gangrene and osteomyelitis secondary to terlipressin therapy but overcame HRS. To our knowledge, this is the first report of osteomyelitis caused by terlipressin therapy in advanced liver disease, in spite of some reports about terlipressin-induced peripheral necrosis or gangrene.2-4

CASE REPORT

A 71-year-old male, who had been diagnosed as alcoholic liver cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis C (genotype 1b) 7 years previously, was admitted for change of mental status. The patient had history of old pulmonary tuberculosis, a cataract operation 10 years ago and several orthopedic surgeries for the fracture of both lower extremities due to a traffic accident 20 years ago. The patient had no diabetes, and hypertension. Familial history was unremarkable. Smoking history was 40 pack years, and the patient stopped smoking 12 years ago. He had 135 g of daily alcohol (three bottles of raw rice wine) consumption for 30 years. Alcohol intake was discontinued four years ago.

Chronic ill appearance, drowsy mental status, crusts and bruises of lower extremities, and abdominal distension without fluid wave shifting were noted on physical examinations. The patient did not complain of claudication ordinarily. His cirrhosis status was Child-Pugh B without ascites and hypersplenism-related pancytopenia. The initial vital signs were blood pressure 150/70 mmHg, heart rate 64 beats/min, respiration rate 20 breaths/min, and body temperature 36℃. The initial laboratory evaluation revealed WBC 26240 (poly: 85.6%) cells/µL, hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL, platelet 1.76×105 cells/µL, prothrombin time 14.7 seconds, international normalized ratio 1.26 (71%), ammonia 168 µmol/L, blood urea nitrogen 27.3 mg/dL, creatinine 3.16 mg/dL, albumin 2.83 g/dL, total bilirubin 2.11 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase 34 U/L, alanine aminotransferase 16 U/L, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 18 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 220 IU/L, lactate dehydrogenase 605 IU/L, Na 137 mEq/L, K 4.7 mEq/L, Cl 114 mEq/L, HCV RNA 1.9×105 copies/mL and metabolic acidosis. Urine sodium was 61 mEq/L with no proteinuria. Chest X-ray showed mild cardiomegaly and emphysematous change. Non-enhanced abdominal CT was unremarkable. Before admission, he had difficulty in defecation for 4 days. The first impression was grade III (graded with the West Haven Criteria) hepatic encephalopathy caused by constipation. Lactulose enema and administration of empirical antibiotics for infection of unknown origin related to leukocytosis were applied. And six months previously, his creatinine level was only 1.63 mg/dL. We suspected of type II hepatorenal syndrome overlapped with hepatic encephalopathy.

Although the combination therapy of fluid replacement and diuretics started, his creatinine level was elevated to 4.02 mg/dL during 10 days. The urine output for 24 hours decreased to 500 mL. The patient was diagnosed with HRS on the basis of the criteria outlined by the International Ascites Club.5

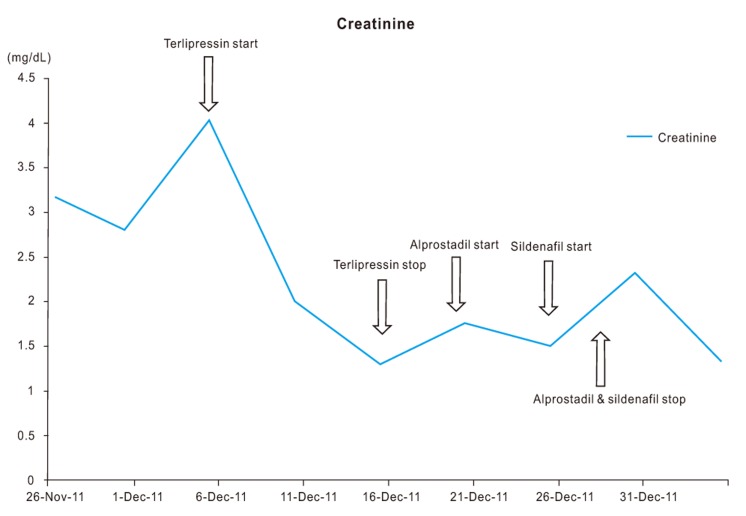

On the admission day 11, intravenous terlipressin along with albumin (20%, 100 mL) was administered for the management (1 mg q 4 hour) of HRS. He complained of severe cramping abdominal pain whenever a single injection of bolus terlipressin was administered. This complication was common, predictable, and thoroughly controlled by means of low-dose analgesics. Total urine output per 24 hours increased to 3,650 mL in 10 days when terlipressin was injected. On the admission day 22, the patient's clinical condition improved, and mentality changed to a clear state. The chemistry panel of the patient decreased: BUN to 30.63 mg/dL and creatinine to 1.29 mg/dL. However, on the day 11 after the terlipressin administration, the patient complained of severe tearing pain of both lower legs, and discoloration, necrosis, and gangrene were found in the 1st and 2nd toes of the right foot and the 1st, 2nd and 3rd toes of the left foot on physical examination. The terlipressin injection was discontinued immediately. These changes progressed to ischemia throughout the feet, accompanied by poor peripheral pulse and delayed wound healing as shown in Fig. 1.

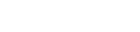

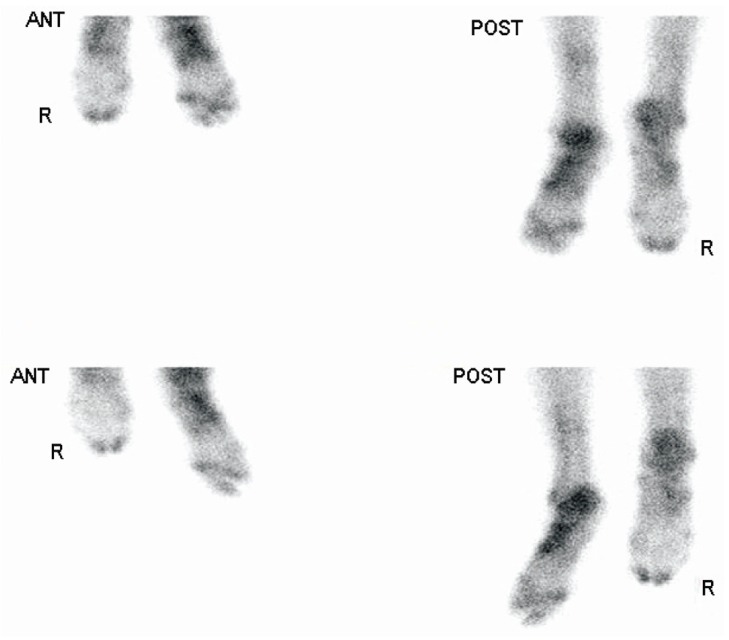

The wounds in both feet were dressed with hydrocolloid solution. The patient still complained of continuous pain in both legs. A 3-phase bone scan showed an increased tracer uptake in the right 1st and 2nd toes, and the left toes and tarsal bone. The diagnosis assumed by the bone scan was osteomyelitis with osteonecrosis of the left foot, and osteomyelitis of the right foot (Fig. 2). However, 3-dimension angiographic CT of lower extremities was not taken due to the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

For prevention of the enlargement of gangrene or necrosis and healing tissue damage, intravenous alprostadil (prostaglandin E1, 10 µg/day) was administered continuously. The patient's serum creatinine stabilized during alprostadil administration. On the 6th day after the administration of alprostadil, an oral sildenafil (cGMP-specific phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor, 50 mg q 12 hour) was added to promote the peripheral circulation. Two days later, his urine output decreased to 445 mL/24h. Serum creatinine level was elevated to 2.8 mg/dL again. The combination therapy of alprostadil and sildenafil was withdrawn promptly. Intravenous furosemide was reintroduced. One week later, the creatinine level decreased again to 1.3 mg/dL, and urine output was held at 2,000 mL/24h. The mental status and clinical condition improved well (Fig. 3).

Though the lesions of the right 1st and 2nd toes were recovered completely by vigorous dressing and medication, the left three toes with severe necrosis and osteomyelitis needed to be amputated finally (Fig. 4). On the admission day 44, a 3-dimension angiographic CT of the lower extremities was taken. It showed moderate stenosis with multifocal calcified plaques at both femoral and popliteal arteries, and mild stenosis at both anterior tibial arteries. The orthopedic surgeons' final decision was amputation of the left leg below the knee including necrotic three toes.

DISCUSSION

Terlipressin is a vasopressin analogue that is converted to lysine vasopressin after the N-triglycyl residue has been cleared by endothelial peptidases. Since its introduction in the early 1990s, it has been used broadly to manage active variceal bleeding and hepatorenal syndrome because of its relative safety and prolonged half-life (6 hour) and easy administration in intravenous boluses.2,6 Although its effect is limited to splanchnic circulation, it also has an effect on systemic circulation as vasoconstrictor.7 The relatively common adverse events that may occur from terlipressin therapy include headache, paleness, abdominal pain and bradycardia. However, few ischemic adverse events affecting the peripheral skin, distal limbs, coronary arteries, intestinal mucosa and genitalia were reported as life-threatening, serious complications.3,7-15

The frequency of ischemic complications after the terlipressin therapy for HRS was revealed to be 5%.4,16 Le Moine et al even reported that there were no ischemic complications after high dose terlipressin (1 mg q 4 hour) was administered to a patient with HRS over 2 months.17 Thus, the ischemic adverse events secondary to terlipressin therapy seem to be limited to that with some risk factors. Some experts concluded that the risk factors of cutaneous necrosis induced by terlipressin were hypovolemia, concomitantly administered pressor drugs and the mode of terlipressin administration.10 Generally, continuous intravenous infusion of terlipressin is not recommended as the mode of administration, since it causes cutaneous necrosis at the infusion site and scrotal necrosis.9 In our case, terlipressin was administered strictly as an intravenous bolus. Other study also reported that an increasing incidences of obesity and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related cirrhosis seemed to raise the ischemic complications of terlipressin.7 Obesity, venous insufficiency and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis were proposed as possible risk factors for the development of ischemic cutaneous complications.18 A recent report also proposed that obesity and hypovolemia be the risk factors associated with terlipressin-induced skin necrosis.8 Although obesity was commonly suggested as a risk factor for ischemia, the body mass index (BMI) of our patient was only 21.8 kg/m2. In present case, possible risk factors which may have caused peripheral gangrene and necrosis appear to be the previous history of several orthopedic operations on lower extremities, the long duration and the dosage of terlipressin administration, atherosclerotic change of vessels of lower extremities which revealed through CT scan, and hypovolemia. Several orthopedic surgeries and atherosclerosis of both lower extremities might have a decisive effect on the patient's vasculature. Furthermore, the deficiency of intravascular volume in advanced liver disease and cardiomegaly might have an influence on peripheral ischemia, in some way or other. Of these suspected risk factors, the duration of terlipressin administration is controversial. Some literatures reported that there was no correlation between the duration of administration and the development of ischemic skin lesions.16

The rescue therapy for ischemia secondary to terlipressin therapy has no consensus and is based on some case reports. Prostanoids (alprostadil and iloprost) are used for the treatment of patients with critical limb ischemia in whom revascularization procedure was inadequate or proved to be unsuccessful. Brodszky et al reported that alprostadil had favorable effects of rest-pain relief and ulcer healing in critical limb ischemia.19 Besides, a recent study reported that sildenafil (50 mg q 12 hour) was effective in severe peripheral ischemia induced by terlipressin, and that the wound also improved in two weeks.13 Based on these reports, intravenous alprostadil and oral sildenafil were administered to the patient in the present case. There are some similarities in adverse reactions of alprostadil and sildenafil such as flushing, arrhythmia, hypotension, heart attack, and anuria. Maybe, these two vasodilators might have an effect on re-aggravating HRS synergically. Another rescue therapy that can be considered is nitrate therapy. Other report suggested that nitrate therapy might be beneficial in ameliorating the ischemic effect caused by terlipressin.8 However, since our patient had intermittent hypotension, this therapy was not considered.

The ischemic complications secondary to terlipressin therapy have some unique distribution. The reported cases mostly showed that the development of skin necrosis is related to the particular distribution of the target receptor of terlipressin - the vasopressin receptor type 1 (V1 receptor) - which is located in smooth muscles of the blood vessels, mainly in the territory of the splanchnic circulation, kidney, myometrium, bladder, adipocytes and skin circulation.20 This fact led us to inspect whether ischemic skin manifestations emerge alongside the distribution of the V1 receptors such as the skin of thigh and abdomen. The emerging time of gangrene or necrosis after the terlipressin therapy generally occurred while the patient was under its administration, except for one case in which it occurred after its discontinuation.8 These findings make it imperative for the physician to monitor the unique distribution of skin alongside the terlipressin therapy and even after the therapy.

Osteomyelitis is known to develop and contiguously spread from the decubitus ulcer or ischemia, hematogenous, and infectious condition. In this case, development of secondary infection by soft tissue necrosis and contiguous spreading of infection seems to be a cause of osteomyelitis. Diagnosis of osteomyelitis is mainly based on radiologic results showing a lytic center with a ring of sclerosis. Culture of specimen taken from a bone biopsy is necessary to identify the specific pathogen. In our case, only radiologic diagnosis was achieved. This pathogenesis appeared to be similar to the diabetic foot in some sides. The morphologic and clinical appearances were also alike between the lesion in this case and diabetic foot. Treatment of osteomyelitis in this patient was conducted through dressing and amputation as a diabetic foot. However, the laboratory tests for diabetes were all unremarkable.

In conclusion, although the peripheral gangrene and osteomyelitis secondary to terlipressin therapy are rare, they may be life-threatening complications. The possible risk factors for ischemia caused by terlipressin therapy in this case might be previous orthopedic surgical history, the duration and the dosage of administration of terlipressin, atherosclerosis of vessels and hypovolemia. The administration of vasodilators such as alprostadil, sildenafil, and nitrate can be considered as a rescue therapy for ischemic complications, but is controversial. Thus, attention to evaluate ischemic complications of peripheral skin and bone during or after terlipressin administration should be paid, especially in patients with ischemic risk factors.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print