Severe ischemic bowel necrosis caused by terlipressin during treatment of hepatorenal syndrome

Article information

Abstract

Terlipressin is a vasopressin analogue that is widely used in the treatment of hepatorenal syndrome or variceal bleeding. Because it acts mainly on splanchnic vessels, terlipressin has a lower incidence of severe ischemic complications than does vasopressin. However, it can still lead to serious complications such as myocardial infarction, skin necrosis, or bowel ischemia. Herein we report a case of severe ischemic bowel necrosis in a 46-year-old cirrhotic patient treated with terlipressin. Although the patient received bowel resection, death occurred due to ongoing hypotension and metabolic acidosis. Attention should be paid to patients complaining of abdominal pain during treatment with terlipressin.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), a form of functional renal impairment, is one of the most serious complications in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis or acute liver failure. The main pathophysiology of development of HRS is reno-vascular constriction.1 In patients with advanced liver cirrhosis, the development of splanchnic vasodilatation causes a reduction in effective arterial blood volume, which leads to increased synthesis of several vasoactive mediators.2,3 Terlipressin is a synthetic analogue of vasopressin, which causes vasoconstriction of splanchnic vessels and improves impaired renal function.2,4 Terlipressin is associated with a much lower incidence of ischemic complications compared with vasopressin, but it may still cause such problems. We report a case of severe ischemic bowel necrosis that developed after use of terlipressin for HRS in a patient with liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

CASE REPORT

A 46-year-old man with underlying liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) secondary to chronic hepatitis B presented with abdominal distension. The patient had undergone hepatic segmentectomy 1 year previously due to HCC. After HCC recurrence, he had been receiving transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), and fifth TACE was done 1 month previously. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) which was taken 2 weeks after the last TACE showed no viable tumor in the liver. But, increased size of lymph nodes in the portocaval space and newly developed ascites were noted. Portal vein was patent without thrombosis.

At admission, electrocardiography was normal and there was no evidence of cardiac dysfunction. Initial serum creatinine was 1.2 mg/dL and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was 12 mg/dL. Albumin level was 3.6 g/dL, aspartate transaminase 136 IU/L, alanine transaminase 137 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase 215 IU/L and total bilirubin 3.8 mg/dL. Hemoglobin level was 14.3 g/dL and platelet count was 284,000/uL. Prothrombin time was 12.8 seconds. A moderate amount of ascites was noted, and urine output decreased. Diagnostic paracentesis and ascitic fluid analysis was done. Albumin was 2.2 g/dL, leukocyte count was 300/mm3 (neutrophil 61%, lymphocyte 10%, monocyte and macrophage 29%), lactate dehydrogenase was 541 IU/L, glucose was 101 mg/dL in ascites, and bacteria was not seen on gram stain and culture of ascites. Serum-to-ascites albumin gradient (SAAG) was 1.4, suggesting ascites from portal hypertension. There was no definite evidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Twenty mg of furosemide combined with 50 mg of spironolactone, was administered for three days.

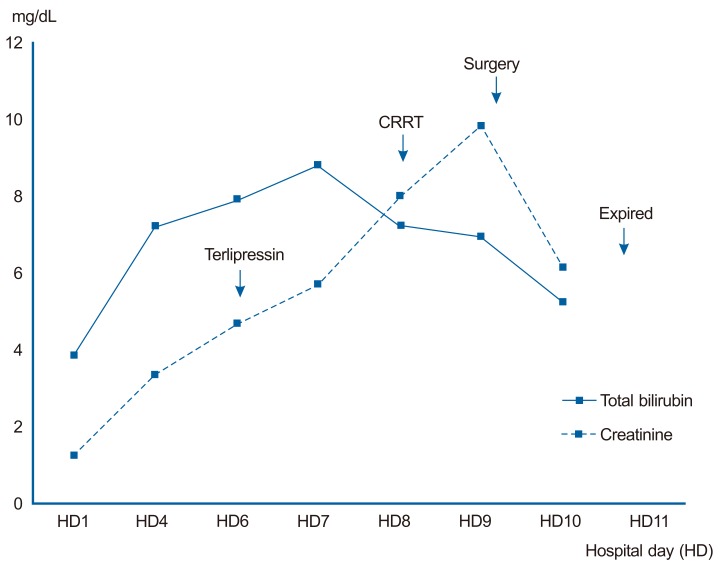

Three days after admission, serum creatinine had increased to 3.31 mg/dL and BUN had increased to 37.6 mg/dL. The fractional excretion of sodium was 0.8%. The diuretics were stopped, and a total of 80 g of albumin was administered and hydration with 1.5 L of normal saline was done for two days to rule out the possibility of pre-renal acute kidney injury. Despite such a treatment, there was no improvement of serum creatinine. No nephrotoxic drug was used and the blood pressure was generally stable. There was no evidence of parenchymal kidney disease such as marked proteinuria or hematuria. Abdominal sonography showed normal echogenicity on both kidney, and urinary tract abnormality was not noted. According to the criteria of International Ascites Club in 2007,5 we diagnosed the patient's renal failure as type I HRS. One mg of terlipressin was intravenously administrated every 6 hours. Because the patient complained of severe abdominal pain after 2 doses of terlipressin, it was stopped. Serum creatinine and BUN increased to 7.95 mg/dL and 84.4 mg/dL, respectively, and hourly urine volume became further decreased (Fig. 1). Continuous renal replace therapy was applied for supporting impaired renal function. But, the patient's abdominal pain aggravated and whole abdominal tenderness appeared. Rebound tenderness was also noted. Abdominal CT revealed that the wall of mid-ileum appeared to be thin and not enhanced with contrast. There were multiple air bubbles in the mesenteric veins and in the bowel wall, suggesting pneumatosis intestinalis (Fig. 2). Otherwise, there was no thrombus within vessel or free air in peritoneal cavity.

Clinical course of the patient according to changes in bilirubin and creatinine levels. CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy.

Abdominal CT revealed thinning of the small-intestine wall (arrowhead) and multiple air bubbles in mesenteric veins (arrow) (A). Air bubbles were also evident in the bowel wall (arrow) (B).

With these findings, the patient was diagnosed with bowel necrosis due to mesenteric ischemia induced by terlipressin. The patient received an emergency bowel resection.

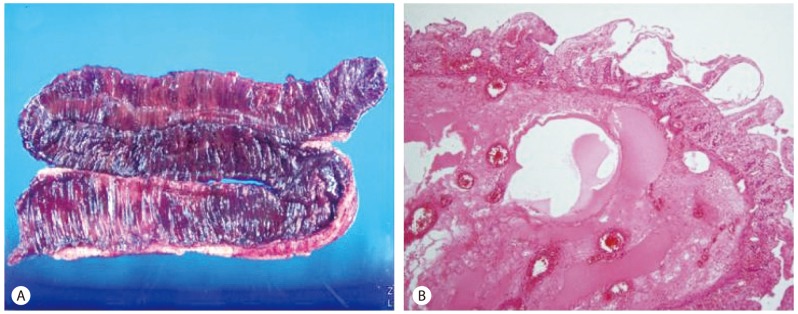

Operative findings demonstrated the small bowel segment below the Treitz ligament to be in an ischemic state. The blood flow was improved after adjusting the direction of bowel mesentery but the infarction of ileum was severe, so approximately 30 cm of it was resected. Grossly, the resected bowel also had ischemic change on serosa and mesentery, and the mucosa was atrophied and black-pigmented on the opening of the bowel lumen (Fig. 3A). Microscopically, there were necrosis and hemorrhages in the bowel wall (Fig. 3B).

Pathologic findings of the resected bowel. Grossly, the mesentery exhibited ischemic changes and the mucosa of the inner layer exhibited atrophy and black pigmentation (A), necrosis and hemorrhagic that were evident microscopically were compatible with ischemic colitis (B) (H&E stain).

There were no any immediate complications associated with surgery, but hypotension and metabolic acidosis persisted. Eventually, the patient died 2 days after operation.

DISCUSSION

Terlipressin, which is a synthetic long-acting analogue of vasopressin with intrinsic vasoconstrictor activity, is widely used in the treatment of cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding and it improves renal function and short-term survival in HRS.6-9

Terlipressin is a vasoconstrictor that acts preferentially on the splanchnic circulation, lowering portal venous pressure. However, all the vasoconstrictors influence the systemic circulation, which may result in ischemic complications. Although terlipressin is associated with a lower incidence of adverse events compared to vasopressin and other synthetic analogues as it is a selective vasoconstrictor, it also can produce systemic effects. An average incidence of adverse events is 12% of patients treated; most are cardiovascular or ischemic complications.3,7 Common adverse events including headache, paleness, abdominal pain and bradycardia are usually mild, but serious complications such as myocardial infarction,8 skin necrosis9 or ischemic colitis may occur.10-12

In this case, the patient complained of abdominal pain after treatment with terlipressin. Abdominal cramping is commonly reported as an adverse event of terlipressin, but most cases are mild and transient.13 However, in this case, pain was severe and continued after discontinuation of terlipressin. In this situation, there were possibilities of acute mesenteric ischemia and bowel perforation, so a CT scan was performed. On the basis of the CT findings, bowel necrosis with pneumatosis intestinalis was diagnosed, and mesenteric thromboembolism or bowel perforation were excluded. There are many conditions associated with pneumatosis intestinalis including pulmonary, autoimmune, infectious, iatrogenic, drug induced, compromised immune state, gastrointestinal, or vascular disease.14 In this case, the patient had no other systemic disease except recent administration of terlipressin. And, ascitic fluid analysis and culture showed no evidence of intra-abdominal infection. Therefore, we concluded that pneumatosis intestinalis developed due to mesenteric ischemia induced by terlipressin. The finding of bowel necrosis with pneumatosis intestinalis seemed to be irreversible. So, we decided to perform a bowel resection.

There are three cases that have reported intestinal ischemia after treatment of terlipressin for variceal bleeding,10-12 but those cases were unrelated to HRS. Also, the Terlipressin and Albumin for Hepatorenal Syndrome Study (TAHRS) trial, which compared the efficacy of terlipressin plus albumin and albumin alone and administered 1-2 mg of terlipressin every 4 hours, reported three cases of suspicious intestinal ischemia during terlipressin therapy for HRS.15 However, those cases were only suspicious events and there was no explanation on outcomes. An important finding in this case is that bowel ischemia developed after administration of two doses of terlipressin (total of 2 mg) and progressed after its discontinuation: The patient received bowel resection eventually. Therefore, this is the first case of severe intestinal ischemia that presented with abdominal pain at regular dose of terlipressin in HRS and progressed to severe bowel necrosis confirmed by pathology after surgery.

Nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia is the result of splanchnic vasoconstriction occurring in response to a variety of systemic insults that diminishes mesenteric blood flow. These include decreased cardiac output (pump failure or arrhythmias), hypovolemia, hypotension (shock, sepsis), rapid digitalization or reaction to vasopressors. Early diagnosis by CT or angiography is the key to the successful management of such patients.16 Underlying causative factors should be corrected urgently, when mesenteric ischemia is diagnosed. Vasodilator therapy may be helpful, and papaverine and prostaglandin are the vasodilators most commonly used. However, referring patients for laparotomy and bowel resection should be considered when there is no response to medical therapy and bowel necrosis is suspected.17

In conclusion, although most of the abdominal pain due to use of terlipressin is mild and resolves after discontinuation of administration, it may develop as an irreversible bowel ischemic necrosis, as exemplified by the current case. Therefore, possible serious complications should be kept in mind and terlipressin needs to be used with caution.

Notes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

BUN

blood urea nitrogen

CT

computed tomography

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

HRS

hepatorenal syndrome

TACE

transarterial chemoembolization