Improved severe hepatopulmonary syndrome after liver transplantation in an adolescent with end-stage liver disease secondary to biliary atresia

Article information

Abstract

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is a serious complication of end-stage liver disease, which is characterized by hypoxia, intrapulmonary vascular dilatation, and liver cirrhosis. Liver transplantation (LT) is the only curative treatment modality for patients with HPS. However, morbidity and mortality after LT, especially in cases of severe HPS, remain high. This case report describes a patient with typical findings of an extracardiac pulmonary arteriovenous shunt on contrast-enhanced transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), and clubbing fingers, who had complete correction of HPS by deceased donor LT. The patient was a 16-year-old female who was born with biliary atresia and underwent porto-enterostomy on the 55th day after birth. She had been suffered from progressive liver failure with dyspnea, clubbing fingers, and cyanosis. Preoperative arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe hypoxia (arterial O2 tension of 54.5 mmHg and O2 saturation of 84.2%). Contrast-enhanced TEE revealed an extracardiac right-to-left shunt, which suggested an intrapulmonary arteriovenous shunt. The patient recovered successfully after LT, not only with respect to physical parameters but also for pychosocial activity, including school performance, during the 30-month follow-up period.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is characterized by a defect in the arterial oxygenation, induced by pulmonary vascular dilatation in end-stage liver disease (ESLD). Triads of this syndrome are liver cirrhosis, intrapulmonary vascular dilatation, and altered gas exchange, resulting in hypoxemia.1 Liver transplantation (LT) is the only treatment to cure HPS in a patient with ESLD. The mortality rate after liver transplantation for the HPS is still high, which depends on the preoperative severity of liver disease and HPS, i.e. partial pressure of arterial oxygen. Although some authors suggested that severe HPS was a contraindication to transplantation,2 nowadays, LT is considered as the only curative treatment modality for severe HPS.3,4

We performed a LT for a 16 years-old female patient, who had severe HPS with an end stage liver disease caused by biliary atresia since neonate. The aim of this case report is to share our successful treatment experience with LT for an adolescent who had severe HPS with typical physical findings and contrast-enhanced echocardiography that was treated successfully by LT.

CASE REPORT

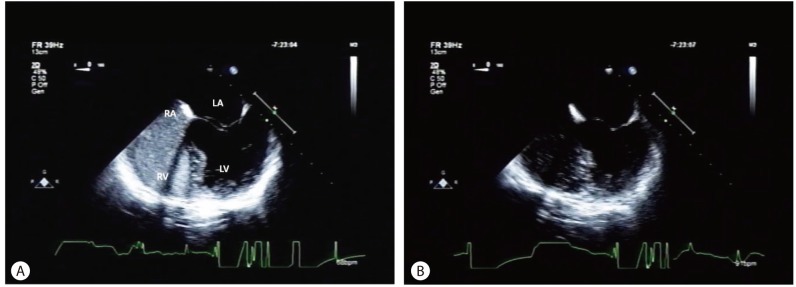

A 16 years-old female was born with biliary atresia, and she underwent porto-enterostomy (Kasai's procedure) on the 55th day after birth. She had intermittent attacks of cholangitis during her childhood. She had been pretty good and developed normally until the age of 15 years. Although she had hepatosplenomegaly, there was no overt symptom. However, she had progressed liver failure aggressively for 6 months before LT. In addition, she was on a bed ridden status because of dyspnea for last 2 months before LT. Both fingers showed clubbing (Fig. 1), ankles were swollen and lips were cyanotic, those were suspected as secondary changes of chronic respiratory insufficiency. Her chest X-ray showed no abnormal findings, except elevated left diaphragm due to splenomegaly. However, her partial pressure of arterial oxygen and arterial oxygen saturation was markedly decreased (PaO2 54.5 mmHg, O2sat 84.2%). Her hepatic and renal profiles were as follows: total bilirubin 42.3 mg/dL, albumin 2.5 g/dL, AST 241 U/L, ALT 93 U/L, INR 2.39, ammonia 2.54 µg/mL and creatinine 0.5 mg/dL. Her Child-Turcotte-Pugh classification was C and MELD (Model of End-Stage Liver Disease) score was 30. The transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) with agitated saline bubble showed an extracardiac right to left shunt, which suggested intrapulmonary arterio-venous shunt (Fig. 2).

Preoperative signs of clubbing fingers were improved after liver transplantation (LT). A. Preoperatively, both fingers showed marked clubbing signs. B. Signs of clubbing fingers were improved at postoperative month 11.

Preoperative contrast-enhanced transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) with agitated saline bubble revealed the existence of a pulmonary arteriovenous shunt. A. Opacification of the right atrium (RA) and right ventricle (RV), with microbubbles being observed after injecting microbubbles. B. Delayed opacification of the left atrium (LA) and left ventricle (LV) was found five cycles later. TEE, transesophageal echocardiography, RA, right atrium, RV, right ventricle, LA, left atrium, LV, left ventricle.

She underwent orthotopic LT donated from a 13-year old deceased donor, in February 2010. For the liver transplant procedure, there shows marked adhesion of entire perihepatic area, and 1.5 cm sized two gallstones in the Roux-limb of jejunal loop, just above the jejunal stenosis, which was removed by jejunotomy. Otherwise, there was no notable event during a routine orthotopic LT procedure. The first PaO2/O2sat level of postoperative 2nd day was 51.3 mmHg/88.0%; however, she was free from ventilator on the morning of that day. In spite of supplying oxygen with a mask, the lower partial pressure of arterial oxygen was persisted, ranging from 36.2 to 53.9 mmHg during the 48 hours after extubation. Although her PaO2 and O2sat level were shown to be very low, her breathing and physical activity with consciousness was rapidly recovered and very stable. She was transferred from the ICU to the isolation ward, on postoperative day 17. Bile leakage was developed from the enterotomy site to remove the gallstones, which was detected by DISIDA scan; it was healed spontaneously by percutaneous drainage and conservative management. Her partial pressure of arterial oxygen remained as low as 55-60 mmHg during a month after surgery. She was allowed to go home on postoperative day 75.

Routine regimen for immunosuppression was applied. Steroid and Simulect® (basiliximab) were administered during anhepatic period, and Prograf® (tacrolimus) and Cellcept® (mycophenolate mofetil) were added on postoperative day 2 and was followed by a routine protocol of our institution. The steroid was tapered until postoperative month 3 and mycophenolate mofetil was used for postoperative 6 months. Tacrolimus monotheray has been maintained since postoperative month 6.

The partial pressure of arterial oxygen improved progressively during the postoperative follow up period and on postoperative month 11, the level was normalized (PaO2 118 mmHg). Follow-up transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) with agitated saline bubble on postoperative 11th months did not show pulmonary arteriovenous shunt any more (Fig. 3). Clubbing of both fingers also recovered to normal shape in postoperative month 11 (Fig. 1). The patient recovered successfully, not only physically, but also pychosocial activity, including school performance during the 48-months follow-up period.

The preoperative pulmonary arteriovenous shunt had disappeared on follow-up contrast-enhanced TEE with preoperative agitated saline bubbles, on the 11th month after LT. A. Opacification of the RA and RV with microbubbles was observed after injecting microbubbles. B. Delayed opacification of the LA and LV was no longer observed after five cycles. TTE, transthoracic echocardiography, RA, right atrium, RV, right ventricle, LA, left atrium, LV, left ventricle.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of HPS in children with liver disease is about 8%.5 A study showed that proportion of biliary atresia is 44% (n=8) in 18 children with HPS.6 The unique pathological feature of HPS is gross dilatation of the pulmonary precapillary and capillary vessels. These dilated capillaries induce un-uniform blood flow, and ventilation-perfusion mismatch emerges as the predominant mechanism of hypoxemia. In most advanced stages, restricted oxygen diffusion into the center of the dilated capillaries also contribute to a part of hypoxemia.1

Therefore, identifying intrapulmonary shunt is important to diagnose HPS. The intrapulmonary vascular shunts are identified by contrast-enhanced transthoracic or esophageal echocardiography (qualitative) or radionuclide lung perfusion scanning, using 99mTc-macroaggregated albumin with brain uptake to measure the shunt fraction (quantitative).6,7 Although radioactive lung-scan is able to stratify the severity of HPS,6,8 contrast-enhanced echocardiogram is a more sensitive and noninvasive method for diagnosis of HPS. In addition, physical examination, clubbing fingers, is important to diagnosis HPS. Although clubbing fingers have lower sensitivity, they have higher specificity, 98% in HPS.9 Therefore, HPS is highly suspected if there is an existence of clubbing fingers in ESLD patients with lower PaO2. In the present study, HPS could be diagnosed preoperatively, based on typical finding of clubbing fingers and extracardiac right to left shunt presumed by contrast-enhanced echocardiogram with agitated saline bubble.

The severity of HPS can be stratified into 4 different grades: mild, AaO2 gradient ≥15mmHg, PaO2 ≥80 mmHg; moderate, AaO2 gradient ≥15 mmHg, PaO2 ≥60 to <80 mmHg; severe, AaO2 gradient ≥15 mmHg, PaO2 ≥50 to <60 mmHg; and very severe, AaO2 gradient ≥15 mmHg, PaO2 <50 mmHg (<300 mmHg while the patient is breathing 100% oxygen).1 The patient's median PaO2 in this case was ≥50 to <60 mmHg, categorized to severe HPS. She was combined with severe ESLD (CTP classification C, MELD score 30), but previous studies showed that no relationship between the severity of HPS and the severity of hepatic dysfunction as assessed on the basis of the CTP classifications or the MELD score.2,6

Currently, there are no effective medical therapies for HPS, and LT is the only reliable treatment to cure the patient. Prognosis of HPS patients who did not undergo LT showed significantly poor, median survival for 24 months with a 5-year survival of 23%.2 Many transplant centers have considered HPS as a contraindication to LT in the early to mid-1980s.7 However, it is now considered as an indication for LT because of improvement in surgical techniques, perioperative care, organ preservation and immunosuppression. The 5-year survival of HPS patients who received LT was 76%,2 which was similar to those without HPS who received LT. Although previous studies showed that the overall mortality rate was relatively high of 16-30%,1,10,11 recent studies showed less overall mortality rate of 5%.3,12 It is known that high postoperative mortality was reported in case of preoperative PaO2 ≤50 mmHg alone or with a shunt fraction of more than 20%.1 Recovery time of lower PaO2 and intrapulmonary shunt after LT are variable, depending on the severity of preoperative lower PaO2. Although lower preoperative PaO2 is related to longer recovery period of HPS resolution after LT,6 in most cases, HPS can be resolved within a year.2

Contrast-enhanced echocardiogram and improvement of clubbing finger are helpful for identifying resolution of HPS during postoperative follow-up.9 The partial pressure of arterial oxygen of our patient was 54.5 mmHg, categorized into severe HPS,1 and resolution of HPS was achieved in 11th months after LT. We could identify the resolution of HPS by disappearance of extracardiac right to left shunt in follow-up contrast-enhanced TTE with agitated saline bubble and improved clubbing of both fingers. In spite of combining severe ESLD presented by CTP classification C and MELD score 30, she recovered completely after LT.

In this report, we presented a patient of HPS, who had typical findings of intrapulmonary arterio-venous shunt detected by contrast-enhanced echocardiography and clubbing fingers with low PaO2, which was successfully treated by LT.

Notes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

HPS

hepatopulmonary syndrome

LT

liver transplantation

TEE

transesophageal echocardiography

TTE

transthoracic echocardiography