Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate monotherapy for nucleos(t)ide analogue-naïve and nucleos(t)ide analogue-experienced chronic hepatitis B patients

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

This study investigated the antiviral effects of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) monotherapy in nucleos(t)ide analogue (NA)-naive and NA-experienced chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients.

Methods

CHB patients treated with TDF monotherapy (300 mg/day) for ≥12 weeks between December 2012 and July 2014 at a single center were retrospectively enrolled. Clinical, biochemical, and virological parameters were assessed every 12 weeks.

Results

In total, 136 patients (median age 49 years, 96 males, 94 HBeAg positive, and 51 with liver cirrhosis) were included. Sixty-two patients were nucleos(t)ide (NA)-naïve, and 74 patients had prior NA therapy (NA-exp group), and 31 patients in the NA-exp group had lamivudine (LAM)-resistance (LAM-R group). The baseline serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level was 4.9±2.3 log IU/mL (mean±SD), and was higher in the NA-naïve group than in the NA-exp and LAM-R groups (5.9±2.0 log IU/mL vs 3.9±2.0 log IU/mL vs 4.2±1.7 log IU/mL, P<0.01). The complete virological response (CVR) rate at week 48 in the NA-naïve group (71.4%) did not differ significantly from those in the NA-exp (71.3%) and LAM-R (66.1%) groups. In multivariate analysis, baseline serum HBV DNA was the only predictive factor for a CVR at week 48 (hazard ratio, 0.809; 95% confidence interval, 0.729-0.898), while the CVR rate did not differ with the NA experience.

Conclusions

TDF monotherapy was effective for CHB treatment irrespective of prior NA treatment or LAM resistance. Baseline serum HBV DNA was the independent predictive factor for a CVR.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major cause of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) worldwide. The primary treatment goal of chronic HBV infection is to prevent the development of liver cirrhosis and HCC. The natural course of chronic HBV infection is highly diverse at the individual level, ranging from inactive carriers to end-stage liver disease or HCC.1 While many vira and host factors can affect this course, the serum HBV DNA level is one of the most important factors affecting prognosis.2,3 The long-term suppression of HBV replication is therefore an important goal in the effective treatment of chronic HBV infection.4,5

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) is an oral prodrug of tenofovir, an acyclic nucleoside phosphonate analogue of adenosine 5'-monophosphate, with an excellent safety profile and potent anti-HBV efficacy in adults.6,7 Up to 6 years of treatment with TDF, long term suppression of HBV can lead to regression of fibrosis and cirrhosis without emergence of resistance to TDF in nucleos(t) ide analogue (NA)-naïve patients.8,9 Apart from the demonstrated efficacy in naïve chronic hepatitis B patients, it has been recently reported to be effective in patients who previously failed lamivudine (LAM) and/or adefovir (ADV).10,11,12 However, most of these studies were conducted in region where genotype A or D is dominant, whereas most Korean patients are infected with genotype C HBV.13 TDF was approved for the treatment of CHB in December 2012 in Korea. One-year data showed TDF monotherapy is effective and safe in NA-naïve Korean patients.14 However, there is few data on antiviral efficacy in LAM-experienced or LAM-resistant Korean patients.

We aimed to evaluate the antiviral efficacy of TDF monotherapy in both NA-naïve and NA-experienced patients and clarify TDF monotherapy is also effective in LAM-resistant patients.

METHODS

Patients

Patients with chronic HBV infection who were treated with TDF monotherapy (300 mg/day) for at least 12 weeks between December 2012 and July 2014 at a single center were consecutively enrolled. Patients with coinfection with hepatitis C virus or HIV and patients who have experienced multi-drug resistance and were not indicated for TDF monotherapy were excluded. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Ilsan Paik Hospital, Inje University College of Medicine, Goyang, Korea.

Data collection

History of previous antiviral treatment, antiviral drug resistance, presence of cirrhosis and adherence to medication were collected. HBeAg, HBeAb, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and serum HBV DNA were also collected at baseline and every 12 weeks. Viral mutation tests were performed at baseline in NA-experienced patients and in patients with virological breakthrough (VBT).

Laboratory assay

Serologic markers of HBV were tested using commercially available electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA, Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, NJ). Serum HBV DNA levels were measured by real-time PCR using The COBAS® Amplicor assay (Roche Diagnostics, limit of detection 20 IU/mL). Genotypic analysis was done by the restriction fragment mass polymorphism (RFMP) method.

Definition

A complete virological response (CVR) is defined as a decrease in serum HBV DNA to an undetectable level as determined by real-time PCR assay (≤20 IU/mL). A partial virological response (PVR) is defined as a decrease in HBV DNA of more than 2 log IU/mL but with detectable serum HBV DNA at week 48 for entecavir (ETV), ADV and TDF, and at week 24 for LAM and telbivudine (LdT).15 VBT is defined as a confirmed increase in HBV DNA level of more than 1 log IU/mL compared to the nadir HBV level achieved during therapy. Biochemical response is defined as a normalization of ALT (≤40 IU/L). Diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was based on the histological findings or radiological findings together with clinical features indicative of portal hypertension, such as thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/mm3), gastroesophageal varices, or ascites.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarized as the median (interquartile range) or mean±SD. Serum HBV DNA levels were logarithmically transformed for analysis. Continuous variables were compared using the Student's t-test, ANOVA, nonparametric Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate and categorical variables were compared using chi-square test. CVR rate was calculated with Kaplan-Meier's curve and compared with the log rank test. A Cox proportional hazard model including variables with P-values ≤0.1 in univariate analysis and clinically relevant factors was used to identify predictive factors independently associated with the time to a CVR. P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of patients

From November 2012 to July 2014, a total of 212 patients were treated with TDF monotherapy. Among those, 18 patients were excluded for multidrug resistance, and 58 patients were excluded for follow-up duration < 3 months. A total of 136 patients (male 96 (70.6%), median age 49) were finally included in this study. Baseline characteristics of patients were summarized in Table 1.

Ninety-four patients (69.1%) were HBeAg-positive and 51 patients (37.5%) had liver cirrhosis. Median follow-up duration was 56 weeks. The mean baseline serum HBV DNA level was 4.9±2.3 log IU/mL and the mean ALT level was 155±252 IU/L.

Seventy-four patients had experienced prior NA therapy (NA-exp group). Among those, 31 patients had documented antiviral resistance to lamivudine (LAM-R group). Twenty-eight patients have not been tested for genotypic mutation. The reasons for medication change to TDF in NA-experienced patients were PVR (n=45), withdrawal hepatitis after discontinuation of prior NA therapy (n=13), virological breakthrough (n=10), emergence of antiviral resistance (n=2), myopathy (n=2) and pregnancy (n=2). Mean duration of washout period in patients with withdrawal hepatitis was 49.7 weeks. Prior history of NA treatment and types of antiviral resistance were summarized in Table 2. Baseline serum HBV DNA was significantly higher in NA-naïve than NA-exp group (5.9±2.0 log IU/mL vs. 3.9±2. log IU/mL, P<0.01). Baseline serum ALT was also significantly higher in NA-naive patients than in NA-experienced patients.

Virological and biochemical responses to TDF monotherapy

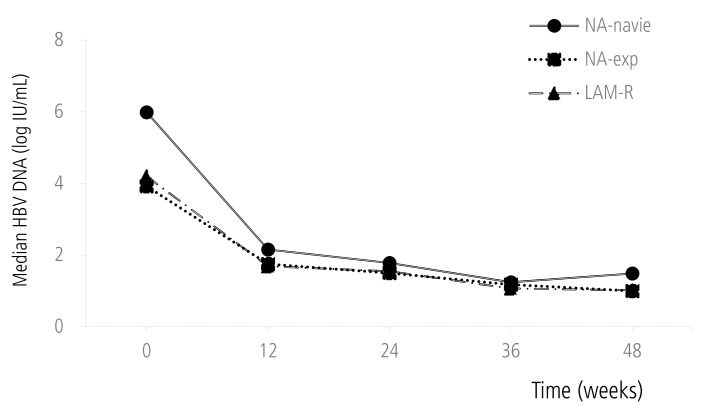

Mean reduction of serum HBV DNA was 3.03 log IU/mL at week 24 and 3.33 log IU/mL at week 48 respectively. Reduction of serum HBV DNA was significantly higher in NA-naïve group than NA-Exp group both at week 24 (4.03 vs. 2.30 log IU/mL, P<0.01) and at week 48 (4.28 vs. 2.46 log IU/mL, P<0.01) (Fig. 1). However, there was no significant difference of the serum HBV DNA reduction between NA-naive and NA-Exp group who had washout periods for previous NA therapy and similar baseline serum HBV DNA with NA-naive patients at week 24 (4.04 vs. 4.59 log IU/mL, P=0.61) and week 48 (4.30 vs. 4.64 log IU/mL, P=0.82).

Mean changes in serum HBV DNA level during TDF treatment.

HBV, hepatitis B virus; NA, nucleos(t)ide analogue; LAM-R, lamivudine resistance.

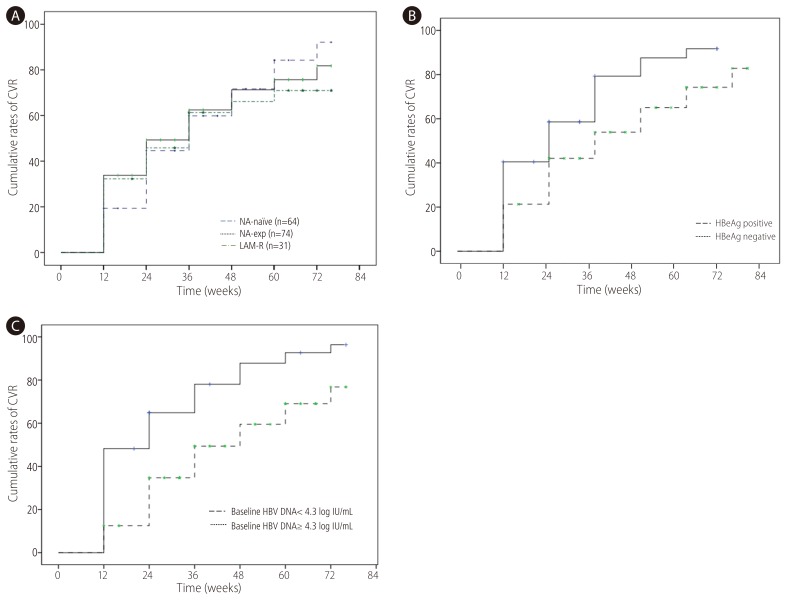

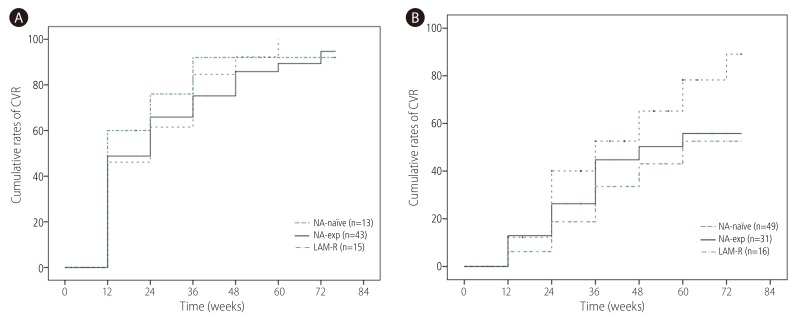

CVR was achieved in 47.1% at week 24 and 71.5% at week 48 respectively. CVR rate at week 48 in NA-naïve group (71.7%) was not significantly different from NA-exp group (n=74, 71.3%) (Fig. 2A). When NA-naïve group was compared with and LMV-R (n=31, 66.1%), there was no significant difference of CVR between two groups. There was no difference of CVR according to types of NA (NA naive 71.7% vs. patients with exposure to LMV only 74.1% vs. patients with exposure to ETV 68.9%, patients with exposure to ADV 72.9%) either. When VR was defined as <60 IU/mL, VR at week 48 was 88.1% in NA-naïve patients, 88.1% in NA-exp group and 87.9% in LAM-R group respectively. CVR rate at week 48 was significantly higher in HBeAg-negative (87.6%) than HBeAg positive patients (75%) (Fig. 2B). Patients with baseline serum HBV DNA <4.3 log IU/mL achieved significantly higher CVR (87.8%) than those with baseline serum HBV DNA ≥4.3 log IU/mL (59.5%) (Fig. 2C). To compensate the difference of baseline serum HBV DNA in comparison of CVR between NA-naïve and NA-exp group, we analyzed CVR between two groups according to baseline serum HBV DNA level. For patients with baseline serum HBV DNA <4.3 log IU/mL, CVR in NA-naïve patients (n=13, 92.3%) was not significantly different compared with NA-exp group (n=43, 82.7%), or LMV-R group (n=15, 92%) (Fig. 3A). For patients baseline serum HBV DNA ≥4.3 log IU/mL, CVR in NA-naïve group (n=49, 65.2%) had tendency to be higher compared with NA-exp group (n=31, 50.3%, P=0.117), or LMV-R group (n=16, 43%, P=0.063) (Fig. 3B).

Cumulative probability of CVR to TDF according to variables. (A) omparison of CVR rate according to NA-experience. CVR rate in NA-naïve group was not significantly different from that in NA-exp group or LAM-R group. (B) Comparison of CVR rate according to HBeAg status. CVR rate was significantly higher in HBeAg negative patients than HBeAg positive patients. (C) Comparison of CVR rate according to baseline serum HBV DNA. CVR rate was significantly higher in patients with serum HBV DNA <4.3 log IU/mL than those with serum HBV DNA ≥4.3 log IU/mL. CVR, complete virological response; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; NA, nucleos(t)ide analogue; LAM-R, lamivudine resistance.

Cumulative probability of a CVR to TDF according to baseline serum HBV DNA. (A) CVR in patents with baseline serum HBV DNA <4.3 log IU/mL. CVR in NA-naïve patients (n=13, 92.3%) was not significantly different from that in NA-exp group (n=43, 85.8%), or LMV-R group (n=15, 92%). (B) CVR in patents with baseline serum HBV DNA ≥4.3 log IU/mL, CVR in NA-naïve patients (n=49, 65.2%) had tendency to be higher as compared with NA-exp group (n=31, 50.3%. P=0.117), or LMV-R group (n=16, 43%, P=0.063). CVR, complete virological response; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; NA, nucleos(t)ide analogue; LAM-R, lamivudine resistance.

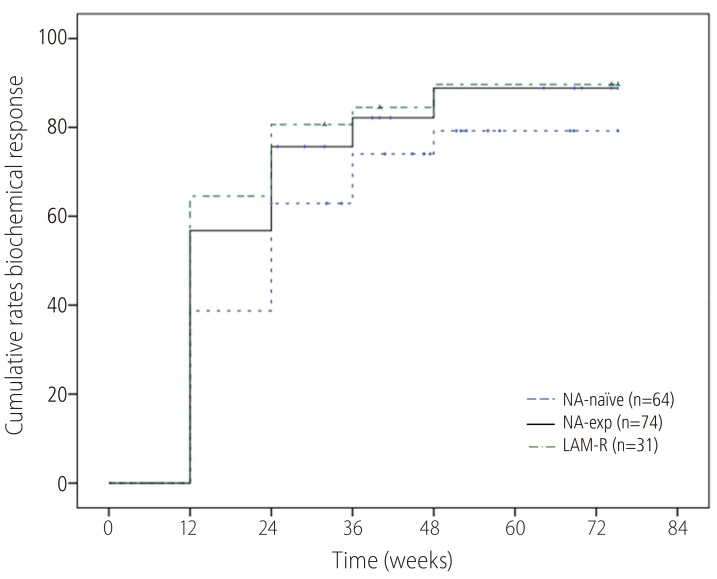

ALT normalization at week 48 was achieved in 82.6% (Fig. 4). Proportion of ALT normalization were also not significantly different compared NA-naïve (79.3%) with NA-Exp (88.9%) or LAM-R (89.7%) group.

Cumulative probability of a biochemical response to TDF monotherapy. The biochemical response rate did not differ significantly between the NA-naïve group and the NA-exp group or the LAM-R group. TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; NA, nucleos(t)ide analogue; LAM-R, lamivudine resistance.

HBeAg loss occurred in 9.6% (9/94). HBeAg loss was 5.0% in NA-naïve patients, 13.0% in NA-exp group and 12.0% in LAM-R group respectively. Virological breakthrough developed in 5 patients but no genotypic resistance was identified. Serum HBV DNA declined without medication change in four patients except one patient who was lost to follow up.

Predictive factors for a complete virological response to TDF monotherapy

Univariate Cox regression analyses of the total patients revealed that baseline serum HBV DNA level (HR, 0.830; 95% CI 0.888 to 0.911) and HBeAg negativity (HR, 1.685;95% CI 1.096 to 2.590) were significantly associated with a CVR. Age, gender, baseline ALT, liver cirrhosis, NA-experience and resistance to lamivudine did not show any association with a CVR. In multivariate Cox proportional hazard model including variables with P-value of ≤0.1 and NA-experience which might be a clinically significant factor, baseline serum HBV DNA was the only predictive factor for a CVR (HR, 0.809; 95% CI 0.729-0.898).

Safety

There were no case who discontinued TDF for significant adverse events during the TDF treatment. Renal function was maintained well in all patients. Also there was no patient with hypophosphatemia during the TDF treatment.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of TDF monotherapy both in NA-naïve and NA-experienced patients, and revealed that TDF monotherapy was highly effective in NA-experienced and LAM-resistant patients as well as NA-naïve patients. Serum HBV DNA reduction seemed to be greater in NA-naïve patients than NA-experienced patients in this study. However these differences of HBV DNA changes might be attributed to lower baseline serum HBV DNA in NA-experienced patients who had been closely monitored and had chance to take TDF in a state of relatively low serum HBV DNA. Actually, serum HBV DNA reduction in NA-experienced patients with similar baseline serum HBV DNA with NA-naïve patients was not different in that in with NA-naive patients. CVR rate and time to CVR were similar between NA-naïve and NA-Exp or LAM-R groups. However, in subgroup analysis for patients with baseline serum HBV DNA ≥20,000 IU/mL to compensate the difference of baseline serum HBV DNA which is the most important predictive factor for CVR, CVR tended to be lower in NA-exp or NA-. This study also investigated the predictive factors for CVR using Cox regression analysis. In univariate analysis, baseline serum HBV DNA and HBeAg were predictive factors for CVR. In multivariate analysis, only baseline serum HBV DNA was an independent predictive factor for CVR. NA-experience and LAM-resistance were not significantly associated with CVR.

TDF monotherapy is highly effective and safe for long-term suppression of HBV in NA-naïve patients.8,9 For patients with NA resistance, combination therapy used to be a standard of care for the concern of multidrug resistance. However, several studies reported the efficacy of TDF monotherapy in NA-experienced patients was not different from that in NA-naïve patients.10,16 In addition, the efficacy of TDF monotherapy was comparable to that of TDF/emtricitibine and TDF/LMV combination therapy in LAM-resistant patients.17,18 There has been no report on TDF resistance in NA-experienced patients yet. Based on these studies, TDF monotherapy was currently recommend for LAM-resistant patients.19

In Korea, we had relatively short clinical experience of TDF therapy for CHB treatment since TDF was licensed in December 2012. TDF was reported to be effective (CVR rate at 1 yr 85.0%) and safe in NA-naïve Korean patients.14 There are also a few studies on the efficacy of TDF monotherapy in NA-experienced patients in Korea. Choi et al. reported the efficacy of TDF monotherapy was comparable to that of TDF and NA combination in patients with genotypic mutation.20 Lee et al also reported the comparison of TDF monotherapy and TDF/LMV combination.21 However, these studies included relatively small numbers of patients, and moreover there have been few studies on head-to-head comparison of the efficacy of TDF monotherapy between NA-naïve and NA-experienced patients in Korea and to address whether the extent of viral suppression is actually not different depending on the prior exposure to NA or antiviral resistance. The results of this study which revealed the similar antiviral efficacy of TDF monotherapy irrespective of NA-experience was consistent with previous studies.17,18 NA-experienced patients in this study had characteristically low baseline serum HBV DNA, which could raise CVR rate and be a confounder in interpreting the effect of NA-experience on CVR. Even after adjusting baseline serum HBV DNA though multivariate analysis, NA-experience was not associated with CVR. However, in subgroups with serum HBV DNA ≥20,000 IU/mL, CVR tended to be lower in NA-experienced or LMV-resistant patients compared with NA-naïve patients.

Viral breakthrough developed in 5 NA-experienced patients who all had poor compliance to medication. No genotypical resistance to TDF was found and HBV DNA declined without medication change in these four patients except one who was lost to follow up. This finding suggested non-adherence to medication was an important cause of viral breakthrough in real clinical setting.

This study was limited by retrospective design, relatively small number of subjects and limited duration of follow-up. Therefore, long-term study for more subjects is mandatory to elucidate the long-term clinical and virological effects of TDF monotherapy in NA-experienced and LAM-resistant patients.

In conclusion, TDF monotherapy was effective for CHB treatment irrespective of prior NA experience or LAM resistance. However, for patients with high serum HBV DNA, CVR in NA-exp or LAM-R group tended to be lower than that in NA-naïve group. Baseline serum HBV DNA was the only independent predictive factor for CVR.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

Abbreviations

ADV

adefovir

ALT

alanine aminotransferase

CHB

chronic hepatitis B

CVR

complete virological response

HBV

hepatitis B virus

LAM

lamivudine

NA

nucleos(t)ide analogue

PVR

partial virological response

TDF

tenofovir disoproxil fumarate