INTRODUCTION

Budd-Chiari syndrome is defined as hepatic venous outflow tract obstruction regardless of the level of the obstruction (anywhere between the small hepatic veins to the junction of the inferior vena cava and right atrium) or the cause of obstruction.1 It is frequently associated with hepatomegaly, abdominal pain, ascites and hepatic dysfunction, and patients with Budd-Chiari syndrome often demonstrate one or more risk factors, including an underlying hypercoagulable state, vascular injury and stasis, venous obstruction by neoplasm or cirrhosis, amebic abscess, sarcoidosis etc. Hypercoagulable states include oral contraceptive use, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, myeloproliferative diseases, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin gene G20210A mutation, and deficiencies of protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III.

marked congestion and fibrosis are the common features of this condition, the histopathological features of Budd-Chiari syndrome are actually very heterogeneous depending on the type of vascular occlusion present, its severity and the duration.2 Obstruction of all three hepatic veins may initially present with fulminant hepatic failure, while involvement of one or two hepatic veins may be associated with only hepatomegaly and mild or transient liver test abnormalities. Portal vein obstruction is commonly seen in severe cases of Budd-Chiari syndrome.2,3 A case of Budd-Chiari syndrome with multiple large regenerative nodules is described, and the histopathological features discussed.

CASE

A 31-year old male patient was referred to the clinic for further evaluation of a suspected right hepatic vein obstruction. He had been previously healthy without prior medico-surgical illnesses, and visited the local clinic complaining of abdominal discomfort and poor oral intake. Computed tomography (CT) showed hepatomegaly with caudate lobe hypertrophy, ascites and occlusion of the right hepatic vein, suggestive of Budd-Chiari syndrome. Laboratory evaluation on admission demonstrated elevated liver enzymes (AST 130 IU/L, ALT 108 IU/L, total bilirubin 2.2 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 1.3 mg/dL, ╬│-GT 74 IU/L) and thrombocytopenia (106,000/┬Ąl). In addition, positivity for antinuclear antibody (ANA; 1:640, speckled pattern), anti-DNA (454.5 AU/mL; reference range: <92.6 AU/mL), anti-cardiolipin IgG (21.5 GPL U/mL; reference range: <10 GPL U/mL), anti-RNP (43.5 AU/mL; reference range: <20 AU/mL), anti-SS-A/Ro (148.9 AU/mL; reference range: <20 AU/mL) and anti-SS-B/La (86.2 AU/mL; reference range: <20 AU/mL), and decreased protein S (38%; reference range: 62~154%) were noted. Lupus anticoagulant screening test was positive.

Under the impression of Budd-Chiari syndrome, antiphospholipid syndrome and Sjogren's syndrome, he underwent heparinization, and a week later a balloonoplasty was performed for the right hepatic vein. However, Doppler ultrasonography revealed persistent thrombosis and occlusion of the right hepatic vein. Stent insertion was performed 5 days later, with a subsequent decrease in pressure gradient and an improvement in his liver function tests. The patient underwent coumadinization with conservative care. Two months later, he was re-admitted to hospital for recurrent ascites and occlusion of the right hepatic vein stent. Balloon dilatation of the stent was attempted, but a follow-up venogram demonstrated re-occlusion. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) was performed two weeks later, after which the patient was followed up regularly. A year later, follow up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed obstruction of the branches of the right hepatic vein branches, ascites, hepatosplenomegaly, and also multiple hypervascular nodules in both lobes of the liver, which were hyperintense on T1-weighted images and iso- to hypointense on T2-weighted images. TIPS ballooning was performed, and two weeks later the patient received a living donor liver transplantation.

PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

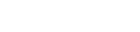

The explanted liver weighed 1,950 g and measured 26.0 ├Ś 19.5 ├Ś 12 cm. The external surface revealed protruding nodules measuring up to 2.0 ├Ś 1.7 cm at segment 5 (Fig. 1). A previously inserted stent was present in the right hepatic vein. On serial sections, multiple randomly distributed well-demarcated yellowish-brown solid nodules were seen, the largest one measuring up to 3.2 ├Ś 2.5 ├Ś 2.3 cm in diameter. At least 15 nodules measuring larger than 0.5cm in diameter were identified grossly, and countless smaller nodules (0.1-0.5 cm) were scattered randomly in the right and left lobes, with relatively sparing of the caudate lobe (segment 1). The nodules had bulging cut surfaces, and some of the larger nodules contained irregular shaped fibrous scars, somewhat resembling focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). The remaining hepatic parenchyme showed ill-defined patchy areas of congestion in the right lobe and the caudate lobe. There was no definite macroscopic evidence of hepatic vein or portal vein occlusion.

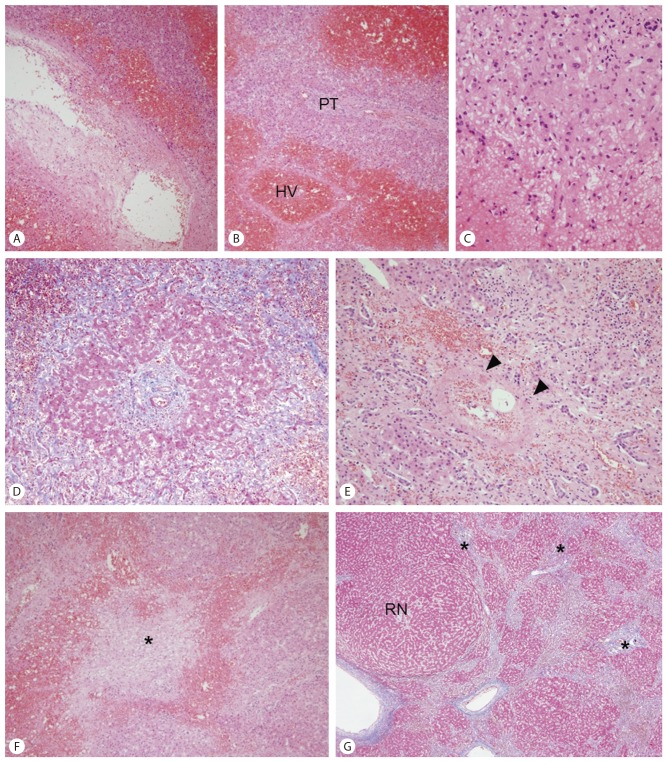

On microscopic evaluation, large and medium-sized small hepatic veins frequently demonstrated variable degrees of fibrous intimal thickening (Fig. 2). Sinusoidal congestion and hemorrhage was seen in the hepatic parenchyme predominantly in the centrilobular zones around the occluded hepatic veins, with marked sinusoidal dilatation, extravasation of erythrocytes into the spaces of Disse and atrophy of hepatocytes. The portal tracts and periportal hepatocytes were relatively spared in some areas, resulting in a venocentric (reverse-lobulation) cirrhosis pattern. However, in other areas hepatic parenchymal extinction was seen also involving porto-periportal regions, and small/medium-sized portal veins were frequently occluded. Fibrous septa were seen bridging the portal tracts and hepatic veins, creating the venoportal cirrhosis pattern. No significant histological changes were seen in the large portal veins and hepatic arteries. Lobular and portal inflammation was mild, and there were no histological findings suggestive of autoimmune hepatitis.

Many regenerative nodules were seen across the entire liver, ranging from microscopic nodules to large regenerative nodules measuring up to 3.2 cm. The nodules were well-demarcated from the surrounding hepatic parenchyma. Six of the large regenerative nodules were FNH-like nodules, demonstrating irregular shaped fibrous scars at the center of the nodules, some resembling the typical stellate scars of FNH. The fibrous septa contained large vessels with irregularly thickened vascular walls, inflammatory cells and abundant ductular reaction (Fig. 3). The hepatocyte plates were mildly thickened up to 2-cell thickness. No significant cytological atypia was seen. A "map-like" glutamine synthetase expression pattern was seen in the FNH-like nodules. Glypican-3 and heat shock protein 70 were not expressed in the nodules. CD34 immunostaining highlighted the increased sinusoidal capillarization in the nodules.

DISCUSSION

Budd-Chiari syndrome is associated with a variety of histological patterns, depending on the duration of the obstruction, its severity, and the presence of portal vein obstruction, and as vascular occlusion is irregularly distributed in the liver, the histological findings may vary in different areas of the same liver. The histological appearance of this condition in relation to the degree of hepatic and/or portal vein obstruction has been well summarized by Tanaka and Wanless.2

Sinusoidal congestion is seen in the hepatic parenchyme to variable degrees, with sinusoidal dilatation and atrophy of hepatocytes. The spaces of Disse may be infiltrated by erythrocytes in more severe lesions, with hemorrhage in the liver cell plates, and necrosis of hepatocytes and endothelial cells. Contiguous loss of hepatocytes with approximation of portal and hepatic vein regions may ensue, resulting in parenchymal extinction. The pattern of fibrosis in Budd-Chiari syndrome may be veno-centric, veno-portal or mixed veno-centric/veno-portal, and the type of fibrosis present depends on the presence and severity of hepatic vein and/or portal vein obstruction. The obstructing thrombus may be an acute thrombus with fresh hemorrhage, or appear as inflamed granulation tissue with fibrosis and recanalization. If only the hepatic veins are occluded, hepatocellular regeneration may occur around patent portal veins; small hepatic veins are incorporated into and connected by fibrous septa, creating a veno-centric type of cirrhosis. Portal tracts are seen at the center of the cirrhotic nodules. Secondary portal vein occlusion is frequently seen in Budd-Chiari syndrome; this results in the extinction of periportal parenchyme and porto-central-portal bridging (veno-portal cirrhosis). Portal tracts can be recognized in the fibrous septa, and the cirrhotic nodules do not contain portal tracts. Both patterns of cirrhosis are frequently seen (mixed veno-centric/veno-portal) especially in explanted livers as the degree and type of vascular occlusion is irregularly distributed in the liver.

Large regenerative nodules have been found in the majority of livers with Budd-Chiari syndrome, and are considered to represent a reactive rather than neoplastic hepatocellular proliferation.2,3,4 The vascular dynamics of these nodules have been shown to be different from the surrounding parenchyma: large regenerative nodules are characterized by an absence of portal veins and prominent arteries that branch to supply the entire nodule with arterial blood. Drainage is into the hepatic veins which are usually patent in these regions. Some large regenerative nodules have central stellate scars, resulting in an appearance indistinguishable from FNH.2,3,4

Large regenerative nodules, including FNH-like nodules, should be distinguished from hepatocellular neoplasms such as hepatocellular carcinoma; hepatocellular carcinomas have indeed been reported in livers with Budd-Chiari syndrome. Glutamine synthetase immunohistochemistry is being increasingly used in diagnostic practice, either as a part of a panel of markers - along with glypican-3 and heat shock protein 70 - for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma, or for the diagnosis of FNH in which a characteristic "map-like" staining pattern has been recognized.5,6 Glutamine synthetase is typically expressed in the hepatocytes around the central vein, due to ╬▓-catenin activation in the perivenular region, and the expansion of ╬▓-catenin-activated centrizonal region in FNH has been presumed to result in the "map-like" overexpression of glutamine synthetase. Although this pattern of staining has not been recognized in FNH-like nodules in cirrhotic livers, suggesting that FNH and FNH-like nodules in cirrhosis have different pathophysiological origins, it is possible that FNH-like nodules associated with vascular lesions such as Budd-Chiari syndrome and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia may have pathophysiological similarities to FNH.7,8 While glutamine synthetase expression with a "map-like" pattern was seen in our case, glypican-3 and heat shock protein 70 were negative in the nodules, and together with the histological findings (no significant cytological or architectural atypia) the diagnosis of well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma could be excluded.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print