Focal nodular hyperplasia: with a focus on contrast enhanced ultrasound

Article information

INTRODUCTION

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is the second most common tumor of the liver after hepatic hemangioma.1 FNH is usually asymptomatic, rarely grows or bleeds, and has no malignant potential. Therefore, FNH is discovered in most patients incidentally during cross-sectional imaging, angiography, radionuclide liver scanning, or surgery.2 Although FNH usually has no clinical significance, recognition of its radiologic characteristics is important to avoiding unnecessary surgery, biopsy, and follow-up imaging. Despite advances in imaging techniques, it is still difficult to distinguish between FNH and other focal hepatic lesions. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) represents a significant breakthrough in sonography and is being increasingly used to evaluate focal liver lesions.3 Herein we present a case of FNH of the liver and its characteristic CEUS features.

CASE

A 32-year-old male was admitted with the complaint of an asymptomatic liver mass that had been discovered by ultrasonography (US) during a medical check-up (Fig. 1). He had no previous history of medical illness or alcohol intake. Biochemical tests showed that the serum level of alanine aminotransferase was 22 IU/L, aspartate aminotransferase was 19 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase was 75 IU/L, and total bilirubin was 0.6 mg/dL. The levels of tumor markers were alpha fetoprotein at 5.9 ng/mL, carcinoembryonic antigen at 1.1 ng/mL, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 at 7 U/mL. The results for hepatitis B surface antigen, anti-HBs, and anti-hepatitis C virus antibody were negative. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a hypervascular mass with a central scar in S5 of the liver (Fig. 2).

Ultrasonography showed a mixed echoic large mass (6.4×4.8 cm) (arrows) on the right hepatic lobe. There was no evidence of cirrhosis in the surrounding liver tissue.

(A-D) CT images obtained at the same level. A high-density mass (arrows) with a low-density center was evident during the arterial phase (B). During the portal (C) and delayed (D) phases, the mass was iso-or hypodense. (E) T1-weighted MRI showed an isointense lesion with a hypointense central scar (arrows). (F) T2-weighted MRI showed a slightly hyperintense lesion with a more hyperintense central scar (arrows). (G) During the arterial phase, in Primovist (gadolinium EOB-DTPA; Schering, Germany)-enhanced dynamic T1-weighted MRI the lesion was hyperintense but the central scar remained hypointense. (H) At 20 minutes after Primovist injection the lesion remained hyperintense compared to the surrounding liver parenchyma (arrows).

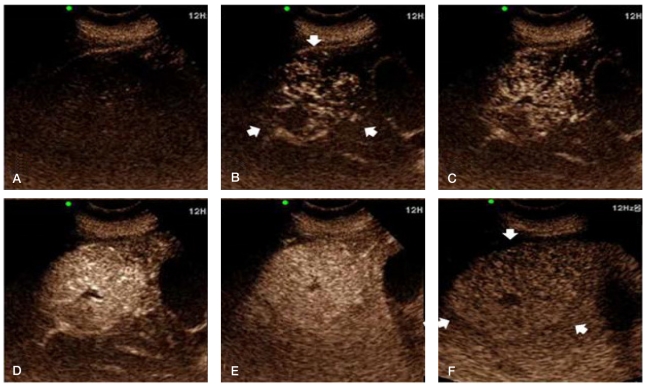

CEUS was subsequently performed using a color Doppler ultrasonic scanner (Prosound alpha 10 premier, Aloka, Tokyo, Japan) with the injection of contrast agent (SonoVue, Bracco Diagnosis, Italy) for real-time dual-flame harmonic imaging of the mass. The mass appeared spoke-wheel like during the arterial phase, and its enhancement persisted until the late phase (Fig. 3, Video at www.koreanjhepatol.org).

(A) Pre-enhanced phase on CEUS. (B-D) During the arterial phase (10~13 seconds after a bolus injecting of contrast agent) there was a spoke-wheel-like centrifugal filling of contrast agent and a markedly hyperechoic mass (arrows), which is attributable to the presence of a central feeding artery and radial arterial vascularity. Sustained enhancement, which appeared slightly hyperechoic or isoechoic relative to the surrounding liver parenchyma, was noticed until the portal venous phase. (E) (45 seconds after contrast-agent injection) and the late phase. (F) (3 minutes after contrast-agent injection). The central scar was hypoechoic during all of the phases.

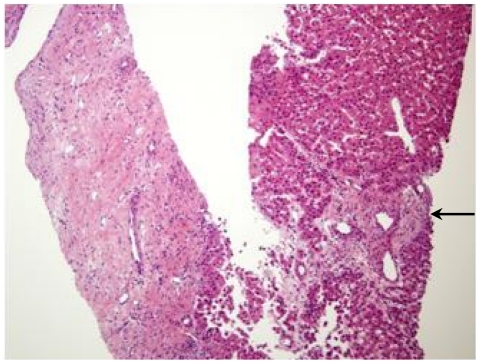

A percutaneous fine-needle-aspiration biopsy was performed under ultrasound guidance, and a histologic examination of the biopsy specimen showed a fibrous scar with anomalous blood vessels (Fig. 4). The characteristic imaging findings and the biopsy results led to a final diagnosis of FNH of the liver. He was recommended to receive regular follow-up of the hepatic lesion.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of FNH is approximately 0.9%, and is more common in females (80~95% of cases) in the third or fourth decade of life.1 Some studies have shown that FNH develops most often in males around the middle age.4 The pathogenesis of FNH is not well characterized. FNH is considered secondary to a hyperplastic response to a regenerative nonneoplasic nodule caused by a congenital vascular malformation. FNH lesions are usually solitary (80% of cases) with diameters >5 cm. Histological characteristics include a connective tissue central stellar scar with a large arterial vessel and a septum.5

FNH presents most commonly as an incidental finding on hepatic imaging (US, CT, and MRI) with no associated symptoms, normal liver function test results, and no elevation of serum levels of tumor markers such as alpha fetoprotein. The reported incidence of symptomatic lesions in large series has ranged from 10% to 59%.6,7 The most common symptom is right-upper quadrant pain. Other symptoms include the sensation of a mass in the right-upper quadrant, nausea, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. Symptoms do not appear until the lesion is large enough to compress surrounding structures or induce the sensation of a mass, which on average occurs when the size is greater than 7 cm.7

Given the benign nature of this lesion, it is essential to differentiate it from more dangerous liver masses, primarily hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, the ability to recognize the radiologic characteristics of FNH is important to avoiding unnecessary surgery, biopsy, and follow-up imaging. FNH is typically diagnosed using several complementary imaging techniques. In patients for whom the diagnosis is not clearly determined from imaging findings, percutaneous needle biopsy, open biopsy, or surgical resection may be needed.

FNH is diagnosed using imaging modalities based of the appearance of a central scar; however, the typical central scar is not demonstrated in every patient. The scar may not be visible in up to 20% of patients. Moreover, a central scar may be found in some patients with fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic adenoma, or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. This limitation applies to all cross-sectional imaging techniques, including US, CT, and MRI.8-10

US examination is a common initial screening method by which FNH is discovered. But US findings are variable, nonspecific. Dynamic CT after the bolus injection of contrast agent adds specificity to the diagnosis, since the lesion becomes hyperattenuating relative to the surrounding liver in the arterial phase-this typically occurs 20~30 seconds after administering the contrast-agent bolus. In the portal venous phase, which occurs 70~90 seconds after the bolus injection, FNH is less conspicuous and becomes isoattenuating with the rest of the liver. During the delayed phase, at typically 5~10 minutes after the bolus injection, FNH is isoattenuating with normal liver tissue. While these observations are characteristic of FNH, they are not specific, with hypervascular adenomas and carcinomas producing similar findings.11

On MRI, most FNH lesions appear from isointense to hypointense on T1-weighted images and from slightly hyperintense to isointense on T2-weighted images.12 The addition of intravenous contrast agent greatly improves the specificity of MRI. FNH demonstrates a vigorous and nearly homogeneous enhancement pattern after the intravenous bolus injection of gadolinium. Malignant lesions also present as early enhancement after gadolinium injection, but their enhancement is usually not homogeneous.13

CEUS is a relatively new diagnostic technique that allows the assessment of contrast-agent enhancement patterns in real time with a substantially higher temporal resolution than other imaging modalities (e.g., CT and MRI) and without the need to predefine scan-time points or to track boluses. Furthermore, CEUS can be repeated due to excellent patient tolerance of ultrasound contrast agents.14 FNH is a hypervascular tumor, and usually appears in CEUS as a markedly hyperechoic mass relative to adjacent normal liver parenchyma in the arterial phase. FNH usually shows sustained enhancement in the portal venous and late phases, and appears slightly hyperechoic or isoechoic relative to the surrounding liver parenchyma.3 A particular of FHN is a spoke-wheel-like fill-in that starts less than 30 seconds after contrast-agent injection, with one study concluding that this sign is present in 96% of lesions larger than 3 cm.15 However, this finding is not pathognomic for FNH when the mass is smaller than 3 cm.16 Thus, CEUS with another contrast agent that allows the evaluation of the enhancement patterns of FNH during the late phase,17 and 3D CEUS, which is highly sensitive at assessing tumor vascularization,18 are promising techniques for the evaluation of FNH lesions, especially those smaller than 3 cm.

CEUS is increasingly being performed on a routine basis and, in the appropriate clinical setting, included as a part of the suggested diagnostic workup of focal liver lesions, and this has improved patient management and the cost-effectiveness of therapy. This case report has shown the typical imaging patterns of FNH in CT, MRI, and CEUS. Especially in CEUS, FNH shows spoke-wheel-like contrast-agent filling during the arterial phase, which is pathognomic for its diagnosis.

SUMMARY

Despite advances in imaging techniques and the ability to detect hepatic masses, it is still difficult to distinguish between FNH and other liver lesions. CEUS may be a useful diagnostic method for FNH lesions larger than 3 cm that show a typical spoke-wheel pattern.