Hepatitis B screening rates and reactivation in solid organ malignancy patients undergoing chemotherapy in Southern Thailand

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Hepatitis B virus reactivation (HBVr) following chemotherapy (CMT) is well-known among hematologic malignancies, and screening recommendations are established. However, HBVr data in solid organ malignancy (SOM) patients are limited. This study aims to determine hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) screening rates, HBV prevalence, and the rate of significant hepatitis caused by HBVr in SOM patients undergoing CMT.

Methods

Based on the Oncology unit’s registration database from 2009–2013, we retrospectively reviewed records of all SOM patients ≥18 years undergoing CMT at Songklanagarind Hospital who were followed until death or ≥6 months after CMT sessions. Exclusion criteria included patients without baseline liver function tests (LFTs) and who underwent CMT before the study period. We obtained and analyzed baseline clinical characteristics, HBsAg screening, and LFT data during follow-up.

Results

Of 3,231 cases in the database, 810 were eligible. The overall HBsAg screening rate in the 5-year period was 27.7%. Screening rates were low from 2009–2012 (7.8–21%) and increased in 2013 to 82.9%. The prevalence of HBV among screened patients was 7.1%. Of those, 75% underwent prophylactic antiviral therapy. During the 6-month follow-up period, there were three cases of significant hepatitis caused by HBVr (4.2% of all significant hepatitis cases); all were in the unscreened group.

Conclusions

The prevalence of HBV in SOM patients undergoing CMT in our study was similar to the estimated prevalence in general Thai population, but the screening rate was quite low. Cases of HBVr causing significant hepatitis occurred in the unscreened group; therefore, HBV screening and treatment in SOM patients should be considered in HBV-endemic areas.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global health problem, especially in Asia-Pacific region, including Thailand. An estimated prevalence of 5–7% HBV infection among general population in Thailand was recently reported [1]. Unquestionably, chronic HBV infection can lead to chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition, in patients undergoing immunosuppressive treatments, including chemotherapy (CMT), hepatitis B virus reactivation (HBVr) is also a crucial condition. As we know, the immune system plays an important role in HBV control and clearance, and increased viral replication during the period of immunosuppression is observed, normally without hepatitis; but after the level of immunosuppressive therapy was decreased, or withdrawn, e.g., during CMT interval, immune recovery can cause a wide range of liver injuries, from asymptomatic transaminase enzymes elevation (HBVr-related hepatitis) to significant morbidity and mortality [2].

To date, HBVr is a well-known issue among patients undergoing CMT, but most evidence comes from hematologic malignancies, especially lymphoma patients, in which high rates of viral reactivation and a significant proportion of liver failure and death were observed following HBVr episodes, both in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive and occult HBV infection patients [3-7]. A cost-effective study [8] and recommendations for universal HBV screening in hematologic malignancy patients before CMT sessions are established [9-12], and antiviral prophylaxis clearly reduced HBVr rates, and HBVr related mortality in those patients [13,14]. While data regarding HBVr in solid organ malignancy (SOM) patients is far less investigated, the typical scenario was seen in breast cancer patients [15], but data from other primary tumors are sparsely reported [16,17].

Most of hepatology expert’s guidelines globally, i.e., the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) [9], the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) [10], and the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) [11], including our national guideline from the Thai Association for the Study of the Liver (THASL), recommend HBsAg screening in all patients undergoing CMT, and antiviral prophylaxis should be administered before initiation of CMT sessions, which is apparently no doubt for hematologic malignancy patients. However, in SOM patients, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guideline [18] recommends screening for HBsAg only in high risk patients, including in populations in which HBV prevalence is >2%, not all CMT candidates. By the reason that there is limited evidence of HBVr in SOM patients, and the level of immunosuppression in CMT regimens for solid tumor are lower than in hematologic malignancies.

This study aims to determine HBsAg screening rates, HBV prevalence, and the incidence of significant hepatitis from HBVr in SOM patients undergoing CMT in Southern Thailand.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

This is a retrospective single center study based on the Oncology unit’s registration database of Songklanagarind Hospital, a tertiary care center and the only university hospital in Southern Thailand. All medical records were reviewed. Inclusion criteria were: 1) SOM patients of at least 18 years old who underwent CMT at Songklanagarind Hospital between 2009 and 2013 and 2) the patients were followed up at our center for at least 6 months after the discontinuation of 1st line CMT, or until death. Patients with prior CMT treatment from other hospitals, participants in other chemotherapeutic or targeted therapy trials for solid tumor(s) during the study period, and patients without baseline liver biochemistry test before 1st CMT administration were excluded.

Data collection

The baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics data were collected, including, but not limited to, age, gender, primary tumor, performance status, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level, alanine transaminase (ALT) level, alkaline phosphatase level, and, if available, HBsAg status. Among patients who were HBsAg positive, we further explored whether they underwent HBV DNA testing before chemotherapeutic agent administration, and whether they received antiviral prophylaxis.

During CMT sessions and the follow-up period, all eligible patients with available liver biochemistry data were reviewed. If any episode of hepatitis occurred between the first course of CMT and 6 months follow-up period, date of hepatitis, peak level of AST and ALT, cause of hepatitis, and outcome following hepatitis episodes were collected. The cause of hepatitis was defined as HBVr-related hepatitis if it was compatible with the criteria described below. Other causes of hepatitis were according to the doctor’s note in the medical records.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

Definition of terms

HBV screening: HBsAg was tested at any time before CMT initiation.

Patients with HBV infection: Patients who were HBsAg positive.

Significant hepatitis: An elevation of AST or ALT level to more than three times of baseline, and more than 40 IU/L; or AST/ALT increased to the level of more than 100 IU/L [19].

HBVr:

(1) Definite HBVr: Tenfold increase in HBV DNA level or the reappearance of detectable HBV DNA in patients with baseline undetectable HBV DNA [20].

(2) Probable HBVr: Patients with HBsAg positive and 1) other causes of hepatitis were excluded, or 2) were diagnosed in medical records as HBVr.

Significant hepatitis from HBVr: patients who matched the definitions of both HBVr and significant hepatitis

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for baseline demographic data. Quantitative measurements are shown as mean±standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), according to the distribution of the observed values. Categorical data, such as HBV screening rate and HBVr-related hepatitis rate, are presented as a number and percentage. Statistical significance was determined using the chi-square test for qualitative data and non-parametric tests for quantitative data. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the population

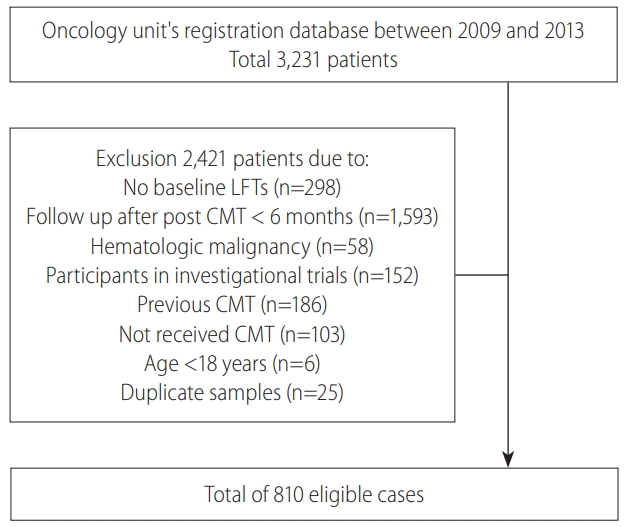

Of 3,231 patients in the Oncology unit’s registration database from 2009–2013, the exclusion criteria were met in 2,421 patients (Fig. 1), resulting in a total of 810 eligible patients in our study. Around two-third of the patients were male, with a mean age of 55 years, and head and neck cancer was the predominant primary tumor in our study population. The mean level of AST and ALT were 28.0 and 25.3 IU/L, respectively. Baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1.

Study population: Of 3,231 patients in the registration database, 2,421 met the exclusion criteria, finally 810 patients were eligible. LFT, liver function tests; CMT, chemotherapy.

HBV screening and management

In the 5-year study period, the overall HBsAg screening rate before CMT initiation in SOM patients in our study was 27.7% (n=224), and only 4.6% were screened for hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc). There was no difference in baseline characteristics between the screened and unscreened groups, except for patients with colorectal and other gastrointestinal and hepatopancreatico-biliary cancer had a greater proportion of HBsAg testing than other primary tumor patients (Table 2).

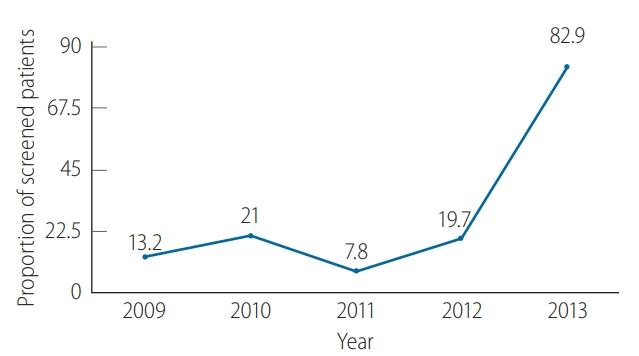

Figure 2 demonstrates the proportions of solid tumor patients who underwent HBsAg screening before CMT, which were quite low from 2009–2012, as less than one-fourth of patients were screened. The HBV screening rate increased markedly to 82.9% in 2013 (P<0.001).

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) screening using HBV by year. Low screening rates were observed in 1999–2012 and increased to more than 80% in 2013.

Among the patients who were screened, the prevalence of HBsAg positive was 7.1%, the median baseline HBV DNA before CMT was 95 IU/mL (IQR 0–2,730 IU/mL), and 75% of them received prophylactic antiviral treatment before CMT.

HBVr

In the subgroup of patients who were HBsAg positive (16 patients) before CMT administration, 25% did not receive antiviral prophylaxis. In untreated group, none had HBV DNA follow-up data during and post CMT treatment; hence HBVr rates, using the aforementioned definition, cannot be determined. While in patients who received prophylactic antiviral therapy, 58% had HBV DNA follow-up data, and none of them developed HBVr. Significant hepatitis from other causes occurred insignificantly different in both antiviral-treated and untreated patients.

Among patients without baseline HBsAg screening before CMT (the unscreened group), the exact HBVr rate cannot be determined, but 3 cases of significant hepatitis from HBVr were documented in this group of patients during follow up.

Causes of significant hepatitis in study population

As the retrospective manner of the study, HBV DNA data were not systematically tested and collected in all patients. We then checked for the patients who developed significant hepatitis (as the definition mentioned in the methods section above) within 6 months after first CMT session. And look for the causes of the significant hepatitis episodes.

Of all 810 enrolled patients, with a median follow-up time of 6 months (as of only 0.98% of the patients died before complete 6-month follow-up period after the first CMT session), significant hepatitis from any causes were observed in 71 patients (8.8%), 37 in unscreened group, and 34 in screened group. Cause of significant hepatitis was defined as probable HBVr in 3 cases, all of them were in unscreened group, while no case of significant hepatitis from HBVr was found in screened group. Other causes of significant hepatitis were shown in Table 3. The most common causes of significant hepatitis in SOM patients were progression of disease (39.4%), and unknown cause (35.2%), respectively.

Clinical outcome after significant hepatitis from HBVr

Of the 3 cases of significant hepatitis from HBVr in this study (Table 4), no significant morbidity or mortality related to HBVr was found. Delayed CMT sessions were observed in 2 patients, both of which occurred in 2012. The other patient’s hepatitis episode occurred after completion of CMT. No hospitalization or liver failure associated with reactivation events were observed. And by reason of the low number of HBVr-related hepatitis episodes that was observed in the present study, the risk factor associated with HBVr-related hepatitis cannot be identified.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to define HBV screening and reactivation in solid tumor patients in Thailand. From our study, the prevalence of HBV infection in SOM patients (7.1%) is comparable to the estimated prevalence in the general Thai population (5–7%) [1], and is different from Western countries in the same way as the chronic HBV infection epidemiology [21,22], and it surpasses the threshold prevalence of the ASCO guideline for HBV screening in SOM patients who are candidates for CMT [18].

Despite numerous guidelines recommending HBV screening in such patients [9-12,18], the overall rate of HBV screening in SOM patients in our study was quite low, as only 27.7% of patients underwent HBsAg testing before CMT, the screening rate for anti-HBc was even lower as only 4.6% were screened. This result is concordant with other studies from the USA, as only 3.9–6.2% of patients were screened in MD Anderson’s study [23], and 9.7-10.1% screening was reported by the Mayo Clinic group [22]. In the present study, 2 of 3 significant hepatitis from HBVr cases were recognized in 2012, which, in combination with THASL recommendation that was launched in the same year, may play a role in the expansion of awareness, resulting in a markedly increased screening rate in the last year of the study period (2013). A similar situation was observed in Japan as the release of national guideline led to a significant improvement of HBV screening rates in patients undergoing CMT in Japan [24].

We could not determine the true rate of HBVr (as defined by increased viral replication) as HBV DNA data were not systematically and periodically tested in all patients. We attempted to look at the liver function test data during 6-month follow-up period after first CMT session of those patients to find out whether there were any cases of significant hepatitis caused by HBVr instead. We found that 8.8% of SOM patients developed significant hepatitis within 6 months after CMT, and HBVr was documented as a cause of significant hepatitis in 3 patients (4.2%). All of them were not screened for HBsAg before CMT session, while none of the patients who were screened and received antiviral prophylaxis if positive HBsAg experienced significant hepatitis from HBVr. Even there was no serious complication e.g., hospitalization, liver failure, or death following those 3 reactivation episodes. It is important to note that this might underestimated the true rate of significant hepatitis from HBVr, as only 6 of 40 patients who were noted to have hepatitis from drug induced liver injury (DILI) or unknown were tested for HBsAg or HBV DNA after hepatitis occurred and there might be some cases of HBVr were misdiagnosed to be DILI or unknown cause. In addition, as we collected the data only for 6 months after first CMT session, we might not be able to capture some cases of delayed HBVr (although delayed reactivation is more commonly reported in rituximab-based therapy rather than CMT regimen for solid organ tumors). Moreover, among 586 patients who were unscreened for HBsAg, if we roughly estimate that 7% of them had positive HBsAg (similar to the prevalence in screened group), this will account for an approximated 41 untreated HBV patients, and 3 of them experienced significant hepatitis from HBVr, we think that this is an unneglectable proportion.

In conclusion, the prevalence of HBV infection in SOM patients undergoing CMT in Southern Thailand is 7.1%, similar to the general Thai population. The overall HBV screening rate before CMT administration in SOM patients was quite low but tended to be better in the last year of the study period. Also, one-fourth of patients who were screened and positive HBsAg did not received antiviral prophylaxis. These findings indicated that there still is room for improvement for the management of HBV screening and treatment in SOM patients. And among patients who had significant hepatitis episodes within 6 months after the first CMT session, at least 4.2% were caused by HBVr, and all of them occurred in patients who were not screened, while none occurred in HBV patients who got antiviral prophylaxis. Therefore, HBVr in SOM patients undergoing CMT should not be overlooked, and HBV screening before CMT should be performed especially in the HBV endemic region including Thailand.

Notes

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand, and were performed in accordance with the Helsinki declaration ethical standard.

Informed consent

Informed consent in this study was waived as it is a retrospective study, and case record form was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

Authors’ contributions

Sripongpun P, Sakdejayont S, and Sathitruangsak C designed the research study; Laiwatthanapaisan R and Sripongpun P performed the research, collected the data, and wrote the manuscript; Sripongpun P and Kongkamol C performed data analysis; Chamroonkul N, Dechaphunkul A, and Piratvisuth T provided critical feedback and helped shape the research. All authors approved the final version of manuscript.

Financial support

The research was supported by the grant from Faculty of Medicine, Prince of Songkla University, Thailand.

Conflicts of Interest

Sripongpun P has received speaker honoraria from BMS, and Takeda. Chamroonkul N has received speaker honoraria from BMS, and Roche. Piratvisuth T is an advisory board member of BMS, MSD, Novartis, and Roche; and has received speaker honoraria from Bayer, BMS, GSK, MSD, Novartis, and Roche; he has received research grants from Gilead, and Roche. Laiwatthanapaisan R, Dechaphunkul A, Sathitruangsak C, Sakdejayont S, and Kongkamol C declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to this study.

Abbreviations

AASLD

the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

ALT

alanine transaminase

anti-HBc

hepatitis B core antibody

APASL

the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver

ASCO

American Society of Clinical Oncology

AST

aspartate aminotransferase

CMT

chemotherapy

DILI

drug induced liver injury

EASL

the European Association for the Study of the Liver

HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

HBV

hepatitis B virus

HBVr

HBV reactivation

IQR

interquartile range

SD

standard deviation

SOM

solid organ malignancy

THASL

Thai Association for the Study of the Liver

References

Article information Continued

Notes

Study Highlights

While the immunosuppression level of chemotherary (CMT) in solid organ malignancies is thought to be lower than hematologic malignancies, and whether we should screen hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in this population is controversial. We found that in Thailand, the hepatitis B virus (HBV) screening rates were quite low in 1999–2012. The significant hepatitis caused by HBV reactivation in solid tumor undergoing CMT was accounted for 4.2% of all hepatitis cases (meaning that the true HBV reactivation rates were higher), and all of them were in unscreened group. The HBsAg screening in solid tumor patients undergoing CMT should be recommended, especially in the endemic area.