| Clin Mol Hepatol > Volume 27(2); 2021 > Article |

|

See the commentary-article "Biopsy or cytology for diagnosing hepatic focal lesions?" on page 278.

ABSTRACT

Background/Aims

The core needle biopsy (CNB), fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and touch imprint cytology (TIC) are commonly used tools for the diagnosis of hepatic malignancies. However, little is known about the benefits and criteria for selecting appropriate technique among them in clinical practice. We aimed to compare the sensitivity of ultrasound-guided CNB, FNAC, TIC as well as combinations for the diagnosis of hepatic malignancies, and to determine the factors associated with better sensitivity in each technique.

Methods

From January 2018 to December 2019, a total of 634 consecutive patients who received ultrasound-guided liver biopsies at the National Taiwan University Hospital was collected, of whom 235 with confirmed malignant hepatic lesions receiving CNB, FNAC and TIC simultaneously were enrolled for analysis. The clinical and procedural data were compared.

Results

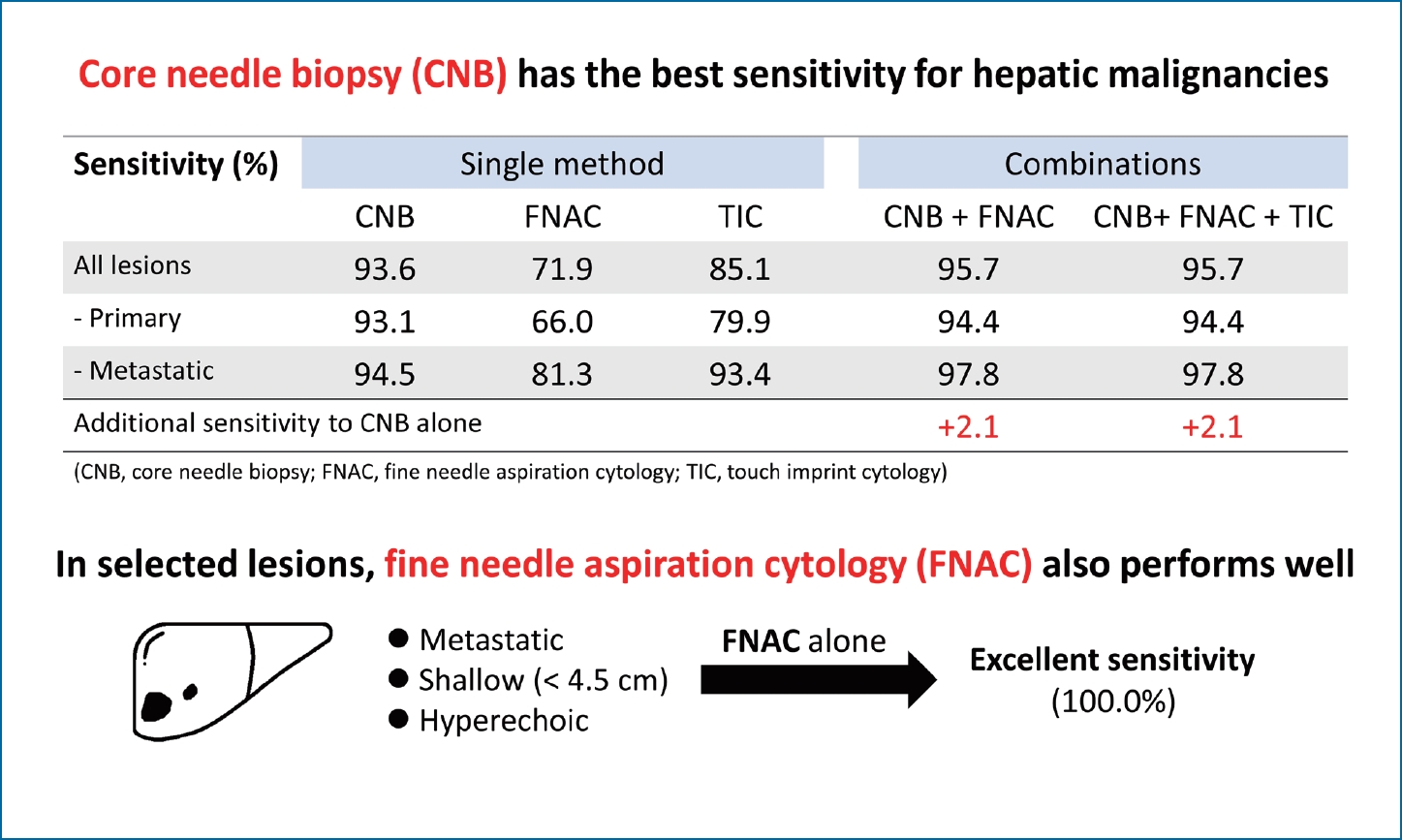

The sensitivity of CNB, FNAC and TIC for the diagnosis of malignant hepatic lesions were 93.6%, 71.9%, and 85.1%, respectively. Add-on use of FNAC or TIC to CNB provided additional sensitivity of 2.1% and 0.4%, respectively. FNAC exhibited a significantly higher diagnostic rate in the metastatic cancers (P=0.011), hyperechoic lesions on ultrasound (P=0.028), and those with depth less than 4.5 cm from the site of needle insertion (P=0.036).

Graphical Abstract

The histological and cytological examination of liver tissues is crucial for the diagnosis of diffuse and focal hepatic lesions on images [1]. The liver biopsy is not only an important tool to correctly diagnose focal liver lesions, but also provide molecular information to guide treatment plans and future studies in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and metastatic cancers [2]. Currently, there are three major methods for percutaneous tissue sampling and subsequent examination, namely core needle biopsy (CNB), fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC), and touch imprint cytology (TIC). The CNB is usually conducted with a 16-gauge core needle and is expected to obtain sufficient tissue. However, the risk of severe complication including intraperitoneal bleeding or needle tract seeding of malignancy is the major concern [3]. FNAC and TIC provide the choice of rapid on-site examination (ROSE), which may be helpful for guidance of clinical practice at the time of sampling [4]. The FNAC is considered to be safer and less costly than CNB because it is usually performed with a 22-gauge fine needle. The drawbacks of the cytological examination include the lack of detailed diagnostic information regarding the tissue architectures. Although TIC does not cause additional risk, it may deplete cellularity and DNA of the obtained CNB specimens [5].

Several studies comparing the CNB and FNAC in multiple organs including liver have generated conflicting and inconclusive results [6]. Some recent studies suggested that the accuracy of the two methods are comparable, and the FNAC might provide higher sensitivity in metastatic liver mass [7]. Another study concluded the specimen from fine needle aspiration is accurate and produces higher tumor fraction for molecular studies than that from CNB [8]. However, most of prior studies focused on the pathologic diagnosis and findings. Little information was provided regarding the clinical and procedural conditions, such as the tumor size, echogenicity and the depth from the insertion site to the tumor margin. In addition, there is no established consensus or criteria for guidance of technique selection.

In this study, we performed a direct comparison between CNB, FNAC as well as TIC in hepatic malignancies receiving real-time ultrasound-guided biopsies, and determined the clinical factors associated with better sensitivity in each method.

From January 2018 to December 2019, a total of 634 consecutive percutaneous ultrasound-guided liver biopsies at the National Taiwan University Hospital were collected. Of these patients, 235 with ultrasound-detectable malignant lesions receiving CNB, FNAC and TIC simultaneously were included for analysis. The flowchart of patient selection is shown in Figure 1. The sampling of the hepatic lesions of interest was guided by the real-time ultrasonography (Aplio 500; Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation, Tochigi, Japan) with linear (PLT-308P; Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation) or convex (PVT-350BTP; Toshiba Medical Systems Corporation) transducers. All patients received local anesthesia prior to the protocolized procedures, which included a FNAC with 4ŌĆō6 axial movements inside the lesion by a 22-gauge needle connected to a 20-mL syringe, followed by the CNB with a spring-loaded 16-gauge needle, and then the TIC via gently touching the obtained tissue on two slides. The samples from fine needle aspiration were released onto two slides equally and then covered by the other two slides, followed by gently and quickly pulling each pair apart. The smears were prepared by both air-drying for LiuŌĆÖs stain and 95% ethanol wet fixation for Papanicolaou stain in every FNAC (four slides) and TIC (two slides). In patients with multiple hepatic tumors, the choice of targeted lesion was based on the combination of the location, size, depth, nearby vessels or organs to achieve maximal safety and yield as possible. The conduction of all the procedures was led by well-experienced interventional hepatologists with more than 100 cases performed per year. The samples of biopsy and cytology were examined by the certified pathologists and cytopathologists separately. ROSE was not the routine practice for liver biopsies in our hospital. Cell blocks were not performed for the cytology specimens. All patients gave written Informed consents for the invasive intervention. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of National Taiwan University Hospital (202006053RINA) and conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The informed consent for the study was waived because it was a retrospective study involving review of medical record only.

The clinical and procedural information was collected by retrospective review of the medical records and images. A standardized record form was used. The clinical information including age, gender and the final diagnosis for the patients was recorded. The procedural information was composed of tumor location, size, number, echogenicity as well as the depth from the skin site of needle insertion to the margin of the targeted tumors. In this study, the histopathological diagnosis of malignancy from the CNB specimens was defined as the gold standard. The results of cytological examination were considered as non-diagnostic in malignant lesions if it showed negative for malignant cell, inadequate specimen or atypia of undetermined significance. If the CNB did not provide the diagnosis of malignancy, either due to inadequate specimens or inaccurate sampling, the final diagnosis was based on subsequent surgical specimens, repeated biopsy, or overall clinical evaluation of images and data from the medical records.

The categorical data was compared by chi-squared and two-tailed FisherŌĆÖs exact tests. The continuous variables were examined by two-sample t-test. The procedural factors, namely tumor location, size, number, echogenicity as well as the depth from the skin site of needle insertion to the margin of the targeted tumors, were comprehensively included in a logistic regression analysis to determine the association with the sensitivity of FNAC. Factors with P<0.1 in the univariate analyses were used in a multivariate logistic regression model. A two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were conducted by PASW Statistics for Windows, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

A total of 235 patients including 148 men and 87 women were enrolled in the study. The mean age was 65.7 years (ranging from 30 to 94 years). Among them, 144 cases were finally diagnosed as primary liver cancers (including 97 HCC, 41 cholangiocarcinoma, three hepatic angiosarcoma, one hepatocholangiocarcinoma, one hepatic malignant spindle cell carcinoma, and one mucinous cystadenocarcinoma), while the other 91 cases were metastatic cancers. A total of 135 cases had single and 100 cases had multiple lesions. The majority of the lesions was located at right lobe (193 of 235). The mean size and depth of the lesions were 4.7 cm and 4.4 cm, respectively. Based on the echogenicity, the target lesions were classified into four groups, including 42 hyperechoic, 118 hypoechoic, nine isoechoic, and 66 mixed echogenicity.

The sensitivity of CNB, FNAC, TIC and combinations for diagnosis of malignancy are shown in Table 1. Among the 235 malignant hepatic lesions, the CNB, FNAC and TIC were diagnostic in 220 (93.6%), 169 (71.9%), and 200 (85.1%) patients, respectively. The sensitivity of CNB was superior to that of FNAC (P<0.001) and TIC (P=0.003). As compared with CNB alone, the combination of CNB plus FNAC or CNB plus TIC provided additional sensitivity of 2.1% and 0.4%, respectively. CNB yielded non-diagnostic results in 15 cases, of which five were diagnostic in FNAC (including HCC, cholangiocarcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, lung adenocarcinoma, and colon adenocarcinoma). There was only a case with negative CNB but positive TIC result (colon adenocarcinoma), in which the FNAC was also positive.

Factors associated the sensitivity of the three methods were analyzed. The sensitivity of CNB was not associated with the origin, number, size, location, depth or echogenicity of the targeted hepatic lesions (all P>0.05). The sensitivity of FNAC was significantly higher in metastatic cancers than in primary liver cancers (81.3% vs. 66.0%, P=0.011), but showed no statistical difference between those with HCC and non-HCC primary liver cancers (63.9% vs. 70.2%, P=0.455). The sensitivity of FNAC was 85.7% in hyperechoic lesions and 68.9% in non-hyperechoic lesions (P=0.028), respectively. Significantly higher sensitivity of FNAC was also observed in the lesions with depth less than 4.5 cm from the site of needle insertion as compared with those with depth equal to or more than 4.5 cm (76.7% vs. 64.0%, P=0.036). Notably, the sensitivity of FNAC reached 100% in the 15 cases with metastatic hyperechoic lesions less than 4.5 cm in depth, in which the CNB provided 14 diagnostic results (CNB sensitivity 93.3%). The number, size and location of the lesions were not associated with the sensitivity of FNAC (Table 2). The two procedural factors reaching statistical significance in the univariate analysis, including the presence of hyperechogenicity and depth less than 4.5 cm, were included in a multivariate logistic regression model (Table 3), and remained independently associated with higher sensitivity of FNAC (odds ratio [OR], 2.654; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.056ŌĆō6.672 and OR, 1.819; 95% CI, 1.014ŌĆō3.264, respectively).

The sensitivity of TIC was higher in metastatic cancers than in primary liver cancers (93.4% vs. 79.9%, P=0.004). Higher yield rate was also disclosed in multiple lesions as compared with single one (91.0% vs. 80.7%, P=0.029). The mean size of the targeted lesions was significantly greater in positive TIC results than that in negative ones, 4.91 cm versus 3.47 cm, respectively (P=0.001). The location, echogenicity and depth of the targeted lesions were not associated with the sensitivity of TIC (Table 4).

In clinical practice, CNB, FNAC and TIC are useful diagnostic tools for the hepatic malignant lesions. The judgement of technique selection is based on a variety of considerations, including the risk, accuracy, cost effectiveness, the institutional and operatorsŌĆÖ preference. No consensus has been established and only limited information guiding the selection of each method for better sensitivity in the diagnosis of hepatic malignancies. In this study, the results by directly comparing the sensitivity of the three methods suggest that CNB may be the most sensitive one (93.6%) for both primary liver cancer and metastatic cancers, and the TIC has comparable sensitivity in metastatic lesions (93.4%). In the clinical practice, prior to receiving liver biopsies, those patients usually undergo ultrasonographic and radiologic examinations, revealing certain degree of suspicion for malignancy [9,10]. The results of the current study, including the sensitivity of each method as well as the factors associated with the sensitivity, may help the clinical physicians select the appropriate techniques with satisfactory sensitivity and safety for patients with suspected hepatic malignancies on images.

The most important benefit from TIC is the utility of ROSE without additional invasive intervention. The ROSE of TIC provides timely information about the adequacy of obtained tissue, thus avoids unnecessary needle passes. Our study confirmed the satisfactory sensitivity of TIC for metastatic lesions, but also observed the suboptimal sensitivity (79.9%) for primary liver cancers. Additionally, depletion of the malignant cells in the obtained tissue of CNB should be considered as a potential problem of the technique [11]. There was a case of metastatic colon adenocarcinoma with positive TIC but negative CNB result in our study, although both of them were derived from the same initial specimen. One possible explanation is the aforementioned condition [5].

This is the first study to directly compare the sensitivity of these common techniques simultaneously for the diagnosis of hepatic malignancies, and then determine the relationship between the procedural parameters and the sensitivity of FNAC. We identified three clinical variables associated with higher sensitivity of FNAC, including metastatic cancers, hyperechoic lesions on ultrasonography, and superficial lesions with depth less than 4.5 cm from the site of needle insertion. Consistently, a previous retrospective study enrolling 74 patients with liver masses also reported the better sensitivity of FNAC in metastatic cancers than in HCC [7]. Our study revealed a wider difference between the sensitivity of FNAC in diagnosing metastatic cancers and primary liver cancers (81.3% vs. 66.0%). A plausible explanation is that the fine needle aspiration obtains fragmented tissue without the intact architecture and surrounding stroma, so the atypia of hepatocytes on cytology is not sufficient to make the definite diagnosis of HCC. The limitation of cytology in the diagnosis of HCC is a crucial consideration for choosing optimal technique in hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) endemic area, where the incidence of HCC is much higher [12,13]. A recent study collecting 10-year cases (most were metastatic cancers) of hepatic FNA in a single institution in United States, a non-HBV/HCV endemic area, showed higher sensitivity of FNA up to 93.4%; although the cell blocks used in the study may also strengthen the diagnostic ability [14].

However, the discrepancy between the sensitivity of FNAC and TIC exists in our study, either for primary or metastatic cancers, not explained by the limitation of cytology itself, suggesting the procedure-associated factors may influence the accuracy of sampling [15]. For example, the FNAC is performed with a 22-gauge fine needle, while the CNB is conducted with a 16-gauge core needle. The difference between the equipment is not only the amount of obtained tissue, but also the degree of difficulty in reaching the targeted lesions accurately. Mechanistically, the needle was inserted and proceeded with the guidance of ultrasonography. Since this is a 3-dimensional operation based on a 2-dimensional plane of view from the ultrasound probe, a small deviation of the needle from the plane of view may lead to disappearance of the needle tip on sonography. Compared with the 16-gauge needle, the 22-gauge needle is much finer and tends to be bent or curved while penetrating tissue with greater friction or resistance, such as a thick subcutaneous layer or the lateral compression of the needle to the rib. The deviation may be greater if the needle is inserted deeper. This phenomenon may also explain the better sensitivity of FNAC in diagnosing hepatic tumors that were less deep.

The echogenicity of hepatic tumors is associated with the pathological nature of the lesions, including the composition and microscopic architecture, therefore different cancers tend to have distinct features on ultrasonography. HCCs are typically known to be hypoechoic, especially for smaller ones, while the metastatic cancers are prone to be hyperechoic [16,17]. In addition, necrotic tissue (that may be associated with fewer viable malignant cells) is less likely to be hyperechoic on ultrasonography. In the current study, the higher yield rate of FNAC for hyperechoic lesions could be explained by above reasons.

Our data showed that add-on FNAC to CNB led to additional diagnostic value of 2.1%, but the risk of complications in repeated needle insertion should be taken into consideration [18,19]. In contrast, FNAC alone in selected patients was found to be beneficial. Although the overall sensitivity of FNAC was only 71.9%, we identified three clinical parameters (metastatic, hyperechoic and <4.5 cm in depth) significantly associated with higher sensitivity. Furthermore, the sensitivity of FNAC increased to 100% (15/15) in hepatic tumors that matched all three criteria. In some cases, the FNAC was diagnostic for malignancy but the CNB revealed non-diagnostic result. This point may also be explained by the operating features of the techniques; the FNAC allowed more to-and-fro movements during tissue acquisition, creating possibly wider sampling area of lesion in question than that of CNB. Future larger prospective studies may focus on more precise predictors that help select the sampling technique with maximal accuracy and minimal risk.

There were limitations in this study. First, it was a retrospective study conducted in a single tertiary center in Taiwan, and the results need to be validated in other facilities with variable clinical settings. Second, those not receiving these three methods simultaneously were not included in the analysis, therefore selection bias could not be totally avoided. Third, the methods compared in this article were all percutaneous ultrasound-guided procedures, which may be not extrapolated to computed tomography-guided ones. Fourth, only malignant lesions were included in this study, therefore other statistical profiles such as specificity were not presented. Fifth, although the samples were examined by the certified pathologists and cytopathologists for histology and cytology separately, the results were not blinded and may be affected by each other, causing possible bias. Further prospective study with blinding design may be needed to clarify this point in the future.

In conclusion, the sensitivity of CNB is superior to that of FNAC or TIC in hepatic malignancies. Nevertheless, FNAC provides excellent diagnostic sensitivity in selected hepatic malignancies that are shallow (<4.5 cm in depth), hyperechoic, and not typical for primary liver cancers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper was funded by National Taiwan University Hospital (grant number 108-S254) and the Ministry of Science and Technology, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (grant number 107-2314-B-002-036-MY3).

FOOTNOTES

AuthorsŌĆÖ contribution

Study concept and design: SC Huang, SJ Hsu; Data collection: SC Huang, JD Liang; Data analysis and interpretation: SC Huang, SJ Hsu, TC Hong, HC Yang; Drafting the article: SC Huang, JD Liang, SJ Hsu, HC Yang; Critical revision of the article: HC Yang, JH Kao; Study supervision: JH Kao; Final approval of the version to be published: all authors

Figure┬Ā1.

Flowchart of patient selection. CNB, core needle biopsy; FNAC, fine needle aspiration cytology; TIC, touch imprint cytology.

Table┬Ā1.

Sensitivity of CNB, FNAC, TIC and combinations in malignant hepatic lesions (n=235)

Table┬Ā2.

FNAC in malignant hepatic lesions (n=235)

Table┬Ā3.

Procedural factors associated with the sensitivity of FNAC (n=235)

Table┬Ā4.

TIC in malignant hepatic lesions (n=235)

REFERENCES

1. Tapper EB, Lok AS. Use of liver imaging and biopsy in clinical practice. N Engl J Med 2017;377:756-768.

2. Finn RS. The role of liver biopsy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2016;12:628-630.

3. Silva MA, Hegab B, Hyde C, Guo B, Buckels JA, Mirza DF. Needle track seeding following biopsy of liver lesions in the diagnosis of hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2008;57:1592-1596.

4. Walia S, Aron M, Hu E, Chopra S. Utility of rapid on-site evaluation for needle core biopsies and fine-needle aspiration cytology done for diagnosis of mass lesions of the liver. J Am Soc Cytopathol 2019;8:69-77.

5. Rekhtman N, Kazi S, Yao J, Dogan S, Yannes A, Lin O, et al. Depletion of core needle biopsy cellularity and DNA content as a result of vigorous touch preparations. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2015;139:907-912.

6. Stewart CJ, Coldewey J, Stewart IS. Comparison of fine needle aspiration cytology and needle core biopsy in the diagnosis of radiologically detected abdominal lesions. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:93-97.

7. Suo L, Chang R, Padmanabhan V, Jain S. For diagnosis of liver masses, fine-needle aspiration versus needle core biopsy: which is better? J Am Soc Cytopathol 2018;7:46-49.

8. Goldhoff PE, Vohra P, Kolli KP, Ljung BM. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy of liver lesions yields higher tumor fraction for molecular studies: a direct comparison with concurrent core needle biopsy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2019;17:1075-1081.

9. Ariff B, Lloyd CR, Khan S, Shariff M, Thillainayagam AV, Bansi DS, et al. Imaging of liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:1289-1300.

10. An C, Rakhmonova G, Han K, Seo N, Lee JY, Kim MJ, et al. A lexicon for hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance ultrasonography: benign versus malignant lesions. Clin Mol Hepatol 2017;23:57-65.

11. Moghadamfalahi M, Podoll M, Frey AB, Alatassi H. Impact of immediate evaluation of touch imprint cytology from computed tomography guided core needle biopsies of mass lesions: single institution experience. Cytojournal 2014;11:15.

12. Nguyen MH, Wong G, Gane E, Kao JH, Dusheiko G. Hepatitis B virus: advances in prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Clin Microbiol Rev 2020;33:e00046-19.

13. Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration, Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, et al. The burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: results from the Global Burden of Disease study 2015. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1683-1691.

14. McHugh KE, Policarpio-Nicolas Md MLC, Reynolds JP. Fine-needle aspiration of the liver: a 10-year single institution retrospective review. Hum Pathol 2019;92:25-31.

15. Park VY, Kim EK, Moon HJ, Yoon JH, Kim MJ. Evaluating imaging-pathology concordance and discordance after ultrasound-guided breast biopsy. Ultrasonography 2018;37:107-120.

16. Yoshida T, Matsue H, Okazaki N, Yoshino M. Ultrasonographic differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic liver cancer. J Clin Ultrasound 1987;15:431-437.

17. Minami Y, Kudo M. Hepatic malignancies: correlation between sonographic findings and pathological features. World J Radiol 2010;2:249-256.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- ORCID iDs

-

Jia-Horng Kao

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2442-7952 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print