Global prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Depression and anxiety are associated with poorer outcomes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, the prevalence of depression and anxiety in HCC are unclear. We aimed to establish the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with HCC.

Methods

MEDLINE and Embase were searched and original articles reporting prevalence of anxiety or depression in patients with HCC were included. A generalized linear mixed model with Clopper-Pearson intervals was used to obtain the pooled prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with HCC. Risk factors were analyzed via a fractional-logistic regression model.

Results

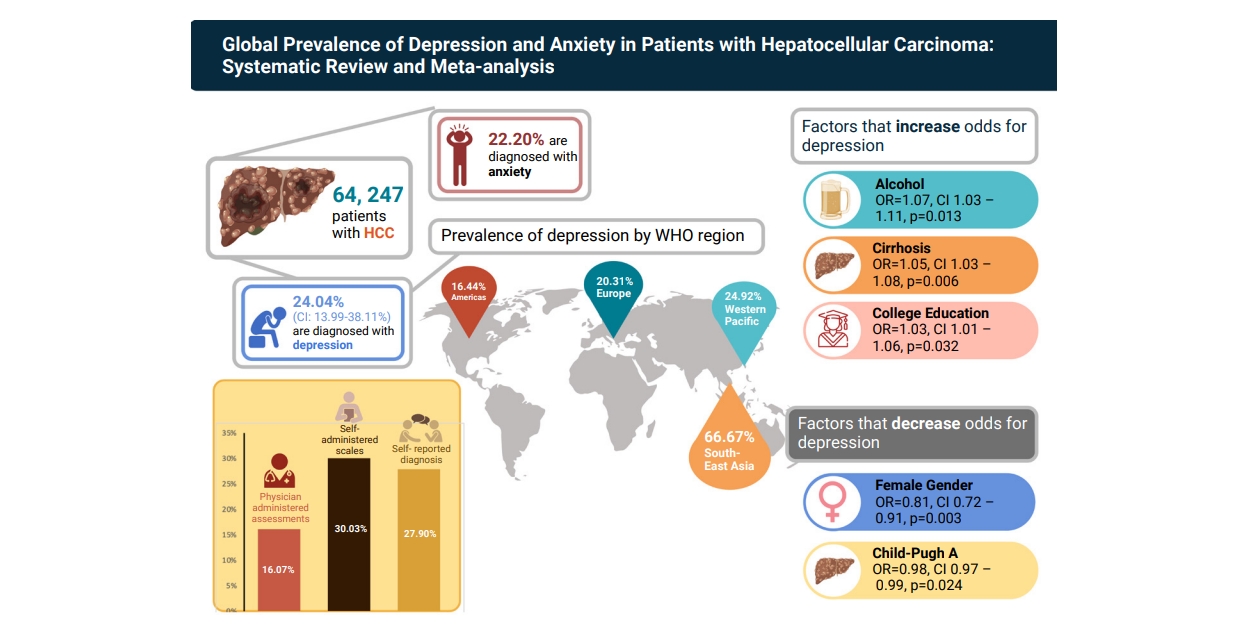

Seventeen articles involving 64,247 patients with HCC were included. The pooled prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with HCC was 24.04% (95% confidence interval [CI], 13.99–38.11%) and 22.20% (95% CI, 10.07–42.09%) respectively. Subgroup analysis determined that the prevalence of depression was lowest in studies where depression was diagnosed via clinician-administered scales (16.07%;95% CI, 4.42–44.20%) and highest in self-reported scales (30.03%; 95% CI, 17.19–47.01%). Depression in patients with HCC was lowest in the Americas (16.44%; 95% CI, 6.37–36.27%) and highest in South-East Asia (66.67%; 95% CI, 56.68–75.35%). Alcohol consumption, cirrhosis, and college education significantly increased risk of depression in patients with HCC.

Conclusions

One in four patients with HCC have depression, while one in five have anxiety. Further studies are required to validate these findings, as seen from the wide CIs in certain subgroup analyses. Screening strategies for depression and anxiety should also be developed for patients with HCC.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1,2]. Despite surveillance programs, the majority of patients with HCC are diagnosed at an advanced stage [3-7]. Overall, the prognosis of HCC is poor, even among patients who have undergone curative treatment [8-11]. Studies have demonstrated poor quality of life (QOL) among patients with HCC due to complications of the cancer and decompensated liver cirrhosis including pruritus, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, and ascites [12,13]. Additionally, treatments for HCC including liver resection and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) have themselves been associated with significant morbidity which reduces QOL [14,15]. In particular, depression and anxiety are common in patients with HCC [16-18], and are associated with poorer survival outcomes and reduced QOL for patients and family members [19-22].

However, existing cohort studies evaluating the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with HCC have produced a wide range of estimates, in part due to different methods of diagnosis [18,23,24]. The prevalence of depression and anxiety among patients with HCC have not been systemically evaluated. In light of these considerations, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the global prevalence and risk factors of depression and anxiety in patients with HCC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

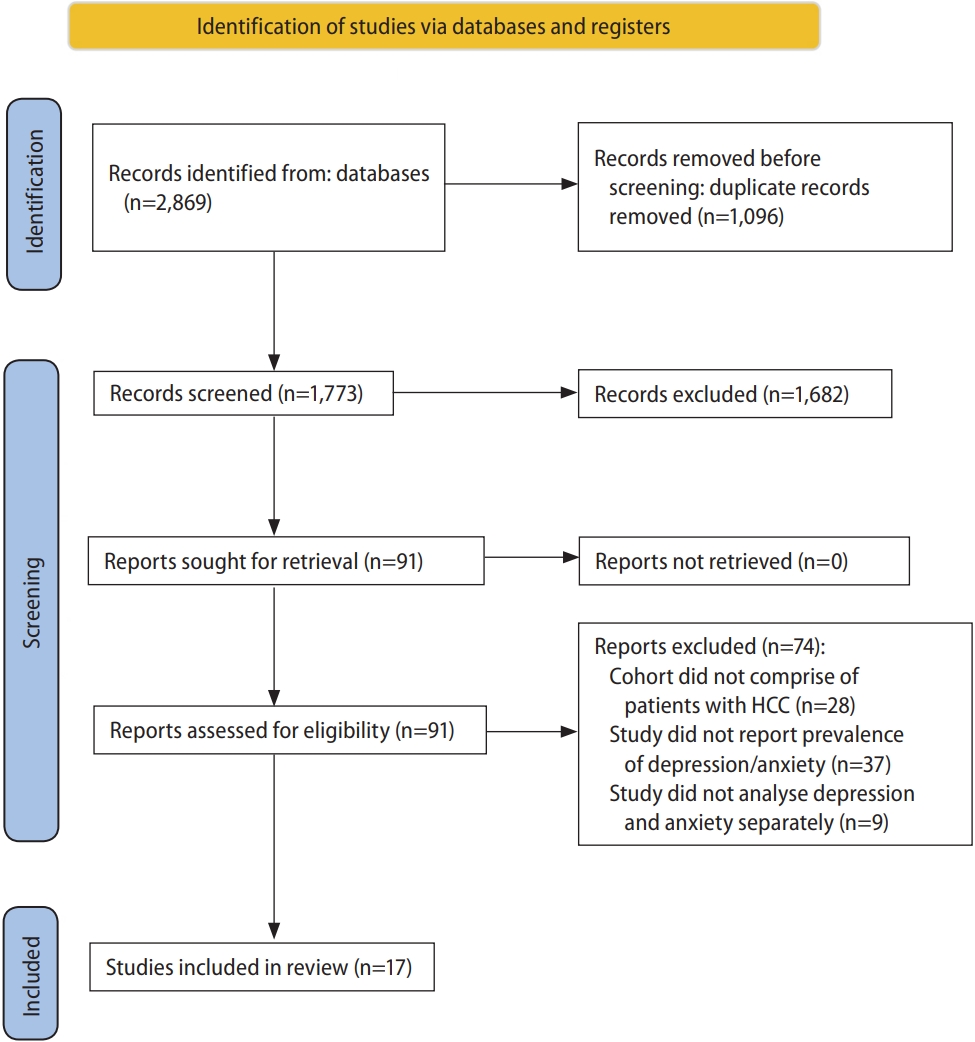

This systematic review and meta-analysis adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRSIMA) in its synthesis [25]. A search was conducted on MEDLINE and Embase databases from inception to 9 February 2022 for keywords and MeSH terms synonymous with “hepatocellular carcinoma”, “depression”, and “anxiety”. The full search strategy is included in Supplementary Table 1. To ensure a comprehensive search, we screened grey literature by reviewing bibliographies of included articles.

Study selection and data extraction

Two authors (DJHT and JNY) independently sieved titles and abstracts, followed by full-text review for eligibility for inclusion. Disputes were resolved through consensus from a third independent author (DQH). Original articles, including retrospective and prospective cohort studies, and randomized-control trials were considered for inclusion, while editorials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses and commentaries were excluded. We included studies written or translated into English language. Studies were included if they reported the prevalence of depression or anxiety in patients with HCC. Studies conducted in pediatric populations were excluded. The diagnosis of depression in included articles was classified into self-reported, self-rated and clinician-rated diagnoses [26]. Self-reported diagnosis included identification of depression through self-reporting of medical history, while self-rated diagnosis of depression comprised of patient responses from the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Korean Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale, Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and the Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI). Clinician-rated diagnosis comprised of depression diagnosed by psychiatrist according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-V), International Classification of Disease, ninth revision (ICD-9) and tenth revision (ICD-10), and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D). In the included articles, a diagnosis of anxiety was done through self-rated scales (HADS, Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale [SAS], and Beck’s Anxiety Inventory [BAI]), or from self-reported physician diagnosis.

Relevant data, comprising study and patient characteristics, were independently extracted by a pair author (DJHT and JNY) into a structured form. The primary outcome of interest was the prevalence of depression, and anxiety in patients with HCC. Study characteristics included author, study period, location, and study design. Patient characteristics included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), diabetes status, history of smoking, history of alcohol consumption, presence of cirrhosis, alpha-feto protein (AFP), employment status, and household income. The proportion of patients with HCC from viral etiologies, and the proportion of patients receiving curative treatment for HCC were also recorded. Curative treatment was defined as liver transplantation, liver resection, or ablation. Where only median and interquartile ranges were reported, we conducted transformation of values into mean and standard deviations via the widely adopted formulas by Wan et al. [27].

Statistical analysis

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed via I2 and Cochran’s Q test values, where I2 value of 25%, 50%, and 75% represented low, moderate, and high degrees of heterogeneity respectively [28,29]. Random effects model was used in all analyses regardless of heterogeneity measures as evidence has demonstrated more robust effect estimates with random effect compared to fixed effect models [30,31]. We used RStudio (version 1.3.1093; RStudio, Boston, MA, USA) for all analyses. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was considered as the threshold for statistical significance.

An analysis of proportions was pooled using a generalized linear mixed model with Clopper-Pearson intervals to evaluate the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with HCC [32,33]. To account for potential sources of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was conducted according to diagnostic criteria for depression (self-reported, self-rated, or clinician-reported diagnosis). Subgroup analysis was also conducted according to the World Health Organization (WHO) regions (Americas, European, South-East Asian, and Western Pacific regions). Additional sensitivity analysis was conducted for studies involving only patients that received curative treatment for HCC. There were insufficient studies to conduct similar subgroup and sensitivity analysis for the prevalence of anxiety in patients with HCC. When sufficient studies were available, analysis on the effect of risk factors on the prevalence of depression in patients with HCC was conducted with a generalized linear model in the binomial family with a logit link and inverse variance weightage via a fractional-logistic regression model. The coefficients were than exponentiated to obtain the odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence interval (95% CI) [34-36]. There were insufficient studies to evaluate the effect of risk factors on the prevalence of anxiety in patients with HCC.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

Quality assessment of included articles was done with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tool [37]. The JBI assessment rates the risk of bias of cohort studies on the premises of appropriateness of sample frame, sampling method, adequacy of sample size, data analysis, methods for identification and measurement of relevant conditions, statistical analysis and response rate adequacy and is the most widely used tool in prevalence meta-analysis. Supplementary Table 2 summarises the quality assessment scores for included articles.

RESULTS

Summary of included articles

The initial search from MEDLINE and Embase yielded 2,869 references, of which 1,773 references were screened after the removal of duplicates. Following the initial title and abstract screen, 91 articles were selected for full-text review, and 17 articles involving 64,247 patients with HCC were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Nine studies described the prevalence of depression in patients with HCC, while eight studies evaluated the prevalence of both depression and anxiety. Depression was identified through physician-administered assessments (DSM-V, ICD-9, and HAM-D), self-rated scales (HADS, Korean CES-D, SDS, and DBI), or through self-reported physician diagnosis. Anxiety was identified through self-rated scales (HADS, SAS, and BAI), or from self-reported physician diagnosis. A summary of the included articles is included in Supplementary Table 2.

Prevalence of depression in patients with HCC

Overall analysis

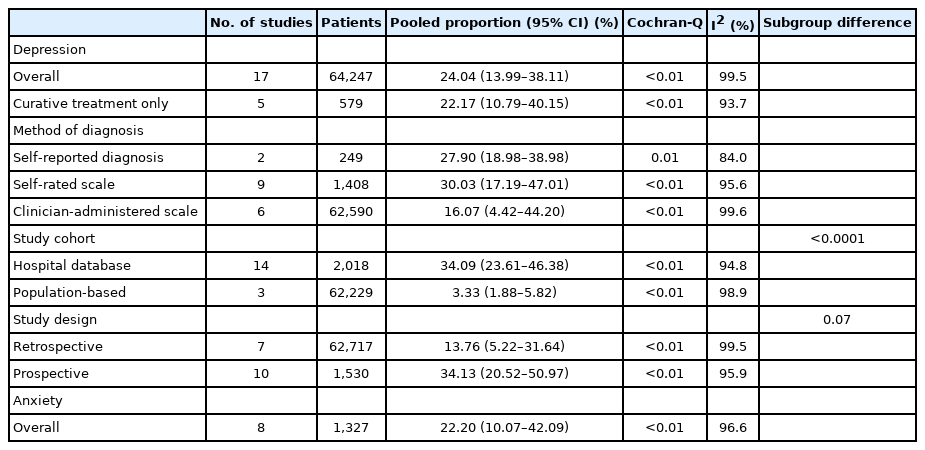

The overall prevalence of depression in patients with HCC was 24.04% (95% CI, 13.99–38.11%; 17 studies, 62,247 patients) (Table 1). To account for heterogeneity potentially arising from differences in diagnosis of depression, analysis was stratified by diagnostic criteria for depression. In studies where depression was identified from physician-administered assessments (six studies, 62,590 patients), the prevalence of depression in patients with HCC was 16.07% (95% CI, 4.42–44.20%), which was lower than the prevalence in studies where depression was identified through self-administered scales (30.03%; 95% CI, 17.19–47.01%; nine studies, 1,408 patients), or through self-reported diagnosis (27.90%; 95% CI, 18.98–38.98%; two studies, 249 patients), although the difference did not reach the conventional threshold for statistical significance (Fig. 2, P=0.60). In a sensitivity analysis of studies involving only patients who received curative treatment for HCC (five studies, 579 patients), the prevalence of depression was 22.17% (95% CI, 10.79–40.15%).

By study design and study cohort

In subgroup analysis by study design, the prevalence of depression was significantly higher in prospective studies (34.13%; 95% CI, 20.52–50.97%; 10 studies, 1,530 patients) versus retrospective studies (13.76%; 95% CI, 5.22–31.64%; seven studies, 62,717 patients) (P<0.0001). There was a numerically higher prevalence of depression in hospital data base studies (34.09%; 95% CI, 23.61–46.38%; 14 studies, 2,018 patients) versus population-based studies (3.33%; 95% CI 1.88–5.82%; three studies, 62,229 patients), although the difference did not reach the threshold for statistical significance (P=0.07).

By WHO region

The prevalence of depression was lowest in the Americas (16.44%; 95% CI, 6.37–36.27%; four studies, 4,956 patients), followed by Europe (20.31%; 95% CI, 4.34–58.87%; two studies, 130 patients), the Western Pacific (24.92%; 95% CI, 11.89– 44.93; 10 studies, 59,065 patients), with the highest prevalence in South-East Asia (66.67%; 95% CI, 56.68–75.35; one study, 96 patients) (P<0.0001; Fig. 3).

Factors associated with depression in patients with HCC

We performed meta-regression of study-level data to determine the association of clinical factors with depression (Table 2). Alcohol consumption, (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03–1.11; P=0.013), cirrhosis (OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03–1.08; P=0.006), college education (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.01–1.06; P=0.032) were associated with increased odds of depression among patients with HCC. Female gender (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.72–0.91; P=0.003) and Child-Pugh A cirrhosis (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.97–0.99; P=0.024) were associated with reduced odds of depression in patients with HCC. Study-level data for age, BMI, diabetes, smoking history, employment status, and income below poverty level were not associated with the risk of depression in patients with HCC.

Prevalence of anxiety in patients with HCC

From pooled analysis of eight studies and 1,327 patients, the prevalence of anxiety in patients with HCC was 22.20% (95% CI, 10.07–42.09%). Data were insufficient to provide subgroup analysis for mode of diagnosis, region, or risk factors.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 studies involving 64,247 patients, the pooled global prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with HCC was 24%. There was a similar prevalence of depression (22%) among patients who underwent curative therapy, and when stratified by mode of diagnosis. The prevalence of depression varied widely by WHO region, with the lowest in the Americas (16.44%) and the highest in South-East Asia (66.67%). The pooled prevalence of anxiety was 22%, but data were insufficient for subgroup analyses or meta-regression, and more studies are required.

These data have important clinical implications as they demonstrate the high prevalence of depression among patients with HCC, which could be attributed to several factors [16]. The profound psychological burden of cancer diagnosis, stress associated with repeated examinations and hospital visits, and adverse effects of various treatment modalities contribute to the increased risk of depression and anxiety in HCC patients [16,17]. Progression of the disease [13], as well as a fear of being terminally ill due to false interpretation of somatic symptoms have also been shown to contribute to increased risk of anxiety in patients with cancer [16]. Due to the high prevalence of psychological conditions in HCC patients, care providers should have a low threshold to screen patients with HCC for depression and anxiety. Among patients with mood disorders, preemptive non-pharmacological strategies such as more comprehensive education and supportive services may be instituted [38]. Care providers may consider early referral of such patients to psychological services that can provide cognitive behavioral therapy and tailored pharmacological therapy as these have been associated with a higher QOL and overall survival [39,40].

The prevalence of depression in studies using self-administered assessments was higher than that in studies that used physician-administered assessments (30% vs. 17%). However, self-administered assessments often over-estimate depression rates due to the misidentification of symptoms of chronic liver disease such as fatigue, poor concentration, lack of appetite as somatic symptoms of depression [41,42]. Furthermore, self-administered assessments are screening tools which are unable to diagnose major depression [43], and physician-rated diagnosis remains the gold standard of diagnosing psychological conditions [44]. Nonetheless, self-rated questionnaires are often used as screening tools in clinical settings due to the ease and speed of administration, and could still provide important data regarding the mental wellbeing of patients with HCC [41,45]. However, there is still no consensus on a validated assessment tool for the screening of mental wellbeing in HCC patients to date. Further studies are required to identify optimal strategies to identify depression and anxiety in patients with HCC.

There was a higher prevalence of depression in patients with HCC in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia regions versus the Americas and Europe. This could be contributed by lower depression literacy in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia, as well as cultural stigmas against mental illness in these regions [46,47]. These could act as barriers against initial health-seeking behavior, increasing the risk of psychiatric disorders in patients with HCC in these regions.

Alcohol consumption, cirrhosis and having a college education level were associated with higher odds of depression. Alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of depressive disorders, related to binge drinking, alcohol abuse and dependence [48-51]. In the existing literature, cirrhosis has also been associated with a poor QOL due to both physical and psychological health deterioration [52,53]. Impaired liver function in patients with cirrhosis often result in decreased QOL, and recurrent hospitalizations associated with cirrhosis can further contribute to the progression of depression [52]. Interestingly, our analysis determined that female gender was associated with decreased odds of depression in patients with HCC. This is in contrast to previous studies by Pedersen et al. [54] and Graham et al. [49], which found that female gender was associated with an increased risk of depression. This has been attributed to differences in hormones, psychological stressors and the effects of childbearing in female patients [18]. Hence, these results should be interpreted with caution, especially since data in females were relatively scarce (<37% female in all included studies).

In context with current literature

A systematic review of the psychological burden in patients with hepatobiliary cancers by Graf and Stengel [55], reported that the prevalence of depressive symptoms was 27.8% (four studies, 799 patients), and the prevalence of anxiety was 39.8% (three studies, 515 patients). However, this study was limited by the relatively small number of patients, and it is unclear if its findings can be generalized specifically to patients with HCC. Our study builds on the data provided by the previous study and provides a global overview of the prevalence of depression and anxiety specifically in HCC. A meta-analysis by Krebber et al. [56] reported that the prevalence of depression in patients with malignancies from all organ systems ranged from 8–24% depending on the method of diagnosis for depression. The data from the current study suggest that there is comparable risk of depression in patients with HCC versus other causes of cancer. However, data regarding the comparative risk of depression in patients with HCC versus other cancers are limited.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first and most comprehensive analysis of the prevalence of depression and anxiety in patients with HCC to date. However, the study is not without its limitations. Firstly, there was significant heterogeneity in the pooled estimates, which persisted despite subgroup/sensitivity analyses by study design, study cohort, WHO region, modality used to diagnose depression and the presence of curative treatment. In subgroup analysis by study cohort, there was significantly lower prevalence of depression in population-based studies versus hospital database studies (3% vs. 34%), contributing to the significant heterogeneity in the overall pooled estimate. The prevalence of depression in population-based studies was likely to be grossly underestimated, and could be related to the limited number of studies (n=3) as well as underdiagnosis, highlighting the need for greater awareness of the risk of depression in patients with HCC. There were limited studies that reported the prevalence of depression in South-East Asia and Europe, resulting in wide CIs for the pooled prevalence of depression in patients with HCC in these regions. Wide CIs were also observed in the subgroup analysis by diagnostic criteria of depression, hence these findings should be interpreted with caution and require validation in future studies. Additionally, there was a paucity of data from the Eastern Mediterranean and African regions, hence further studies are required to determine the prevalence of psychiatric conditions in patients with HCC from these regions. There was also inadequate data for meaningful subgroup analysis for the prevalence of anxiety in HCC patients, and more data are required.

Conclusion

One in four patients with HCC suffer from depression, and one in five suffer from anxiety. Care providers looking after patients with HCC should have a low threshold to screen for depression and anxiety. This would help facilitate timely diagnosis and referral to psychological services as studies suggest poorer QOL and mortality outcomes in patients with psychological conditions. Further studies are required to determine optimal screening strategies for depression and anxiety in patients with HCC.

Notes

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Daniel Q. Huang; Data curation: Darren Jun Hao Tan, Sabrina Xin Zi Quek, Cheng Han Ng; Formal analysis: Darren Jun Hao Tan, Sabrina Xin Zi Quek, Jie Ning Yong, Cheng Han Ng; Data verification: Darren Jun Hao Tan, Sabrina Xin Zi Quek, Jie Ning Yong, Adithya Suresh, Kaiser Xuan Ming Koh; Supervision: Daniel Q. Huang; Writing, original draft: Darren Jun Hao Tan, Sabrina Xin Zi Quek, Jie Ning Yong, Cheng Han Ng; Writing, review, and editing: Darren Jun Hao Tan, Sabrina Xin Zi Quek, Jie Ning Yong, Adithya Suresh, Kaiser Xuan Ming Koh, Wen Hui Lim, Jingxuan Quek, Ansel Tang, Caitlyn Tan, Benjamin Nah, Eunice Tan, Mark D. Muthiah, Nicholas Syn, Cheng Han Ng, Taisei Keitoku, Beom Kyung Kim, Nobuharu Tamaki, Cyrus Su Hui Ho, Rohit Loomba, Daniel Q. Huang; All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Clinical and Molecular Hepatology website (http://www.e-cmh.org).

Search strategy for MEDLINE

Summary of included articles and quality assessment

Abbreviations

AFP

alpha-feto protein

BAI

Beck’s Anxiety Inventory

BDI

Beck’s Depression Inventory

BMI

body mass index

CES-D

Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression

CI

confidence interval

DSM-V

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

HADS

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

HAM-D

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

ICD-10

International Classification of Disease

ICD-9

International Classification of Disease

JBI

Joanna Briggs Institute

OR

odds ratio

PRSIMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

QOL

quality of life

SAS

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale

SDS

Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale

TACE

transarterial chemoembolization

WHO

World Health Organization

References

Article information Continued

Notes

Study Highlights

From pooled analysis of 64,247 patients with HCC, the pooled prevalence of depression and anxiety were 24.04% and 22.20% respectively. Alcohol consumption, presence of cirrhosis, and college education were associated with significantly higher risk of depression in patients with HCC. While further studies are required to validate these findings, this study highlights the high prevalence of mental health disorders in patients with HCC. Screening strategies for depression and anxiety in patients with HCC should be developed to tackle this significant problem.