Chronic hepatitis B with concurrent metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: Challenges and perspectives

Article information

Abstract

The prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) has increased among the general population and chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients worldwide. Although fatty liver disease is a well-known risk factor for adverse liver outcomes like cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, its interactions with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and clinical impacts seem complex. The presence of hepatic steatosis may suppress HBV viral activity, potentially leading to attenuated liver injury. In contrast, the associated co-morbidities like diabetes mellitus or obesity may increase the risk of developing adverse liver outcomes. These findings implicate that components of MAFLD may have diverse effects on the clinical manifestations of CHB. To this end, a clinical strategy is proposed for managing patients with concurrent CHB and MAFLD. This review article discusses the updated evidence regarding disease prevalence, interactions between steatosis and HBV, clinical impacts, and management strategies, aiming at optimizing holistic health care in the CHB population.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatic steatosis: an emerging global health issue

Fatty liver is the hepatic manifestation of systemic metabolic dysregulation and has become an emerging etiology for cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [1] worldwide. It is estimated that nearly a third of people are affected by fatty liver diseases. Moreover, the estimated prevalence is increasing in Asian countries, from 25.3% between 1999 and 2005 to 33.9% between 2012 and 2017 [2]. As a result, the optimal strategy for the diagnosis and management of fatty liver diseases is of top priority at the global public health level.

New concept and nomenclature: metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)

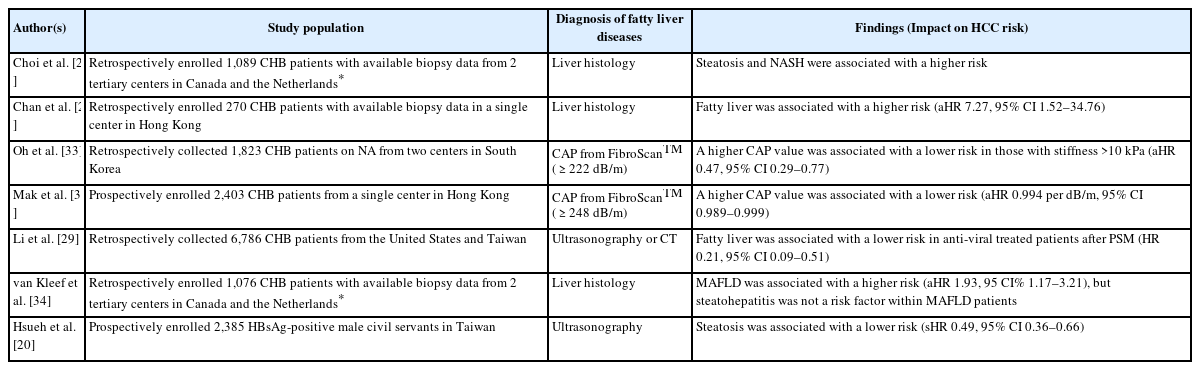

In 2020, a new definition for fatty liver disease, MAFLD, was proposed in an expert consensus meeting [3]. Compared with the traditional definition of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the new criteria of MAFLD do not need to exclude patients with chronic viral hepatitis, excessive alcohol intake, medication-related steatosis, or other chronic liver diseases; instead, the diagnosis of MAFLD is based on the presence of hepatic steatosis, plus one of the following three clinical situations: overweight/obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM), or two metabolic risk factors (Fig. 1) [3]. The evolution of the definition makes the clinical diagnosis easier and has been shown to include more patients with higher disease severity [4-8]. Particularly, unlike NAFLD, the diagnosis of MAFLD can be made for patients with other concurrent chronic liver diseases, including chronic hepatitis B (CHB) [9].

Disease definition of MAFLD. The new criteria do not need to exclude patients with other concomitant liver diseases or alcohol intake. MAFLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; TG, triglycerides; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HOMA-IR, Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance index; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Concurrent MAFLD in the hepatitis B population

Although a lower prevalence of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients than that in the general population has been reported [10], co-existing fatty liver disease among the CHB population is frequently seen in HBV endemic areas. According to a prior meta-analysis of 17 studies, the prevalence of fatty liver was about 29.6% in patients with CHB [11]; in another meta-analysis of 54 studies with 28,648 CHB patients, the pooled prevalence of hepatic steatosis is up to 32.8% [12]; a more recent meta-analysis of 98 studies with 48,472 patients demonstrated an even higher global prevalence of 34.93% [13]. Clinical manifestations, reciprocal interaction, and impacts are essential issues to be addressed. This review article will focus on the interactions between MAFLD and CHB, as well as the management strategies for CHB patients with co-existing MAFLD.

INTERACTION AND IMPACTS

Inverse correlation between steatosis and HBV activity

Regarding the epidemiology, as aforementioned, a lower prevalence and incidence of steatosis in patients with CHB than in the general population has been consistently reported in several studies [10,14,15]; in addition, higher levels of serum HBV DNA were associated with a lower prevalence of fatty liver among patients with CHB [16]. On the other hand, CHB patients with concurrent steatosis tended to have lower viral activity, including lower proportions of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positivity and lower serum HBV DNA levels, as well as higher rates of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance [17-21]. In a study enrolling 506 untreated CHB patients, the level of HBV viral load was lower in those with fatty liver than in those without fatty liver in a dose-dependent manner based on controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) value [18]; in a study of 3,212 untreated CHB patients, the proportions of serum HBeAg positivity, HBV viremia, intrahepatic HBsAg and hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) positive staining on liver tissue were fewer in those with steatosis [17]. Similarly, the inverse correlation between hepatic steatosis and HBV viral activity was confirmed in a recent meta-analysis [12].

The underlying mechanisms for the negative association between hepatic steatosis and HBV viral activity have been explored in animal and cellular models. The hepatic steatosis in an HBV-immunocompetent mouse model fed with high-fat diets significantly attenuated the levels of serum HBeAg, HBsAg, HBcAg, and HBV DNA [22]. In the in vitro model, steatosis inhibited HBsAg and HBV DNA secretion by the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress in hepatocytes [23]. Adiponectin which suppresses hepatic steatosis was found to be a potentially important mediator; a study using the in vitro model of HepG2-hepatitis B virus-stable cells demonstrated that the viral replication was upregulated by adiponectin and was downregulated by the small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) for adiponectin [24]; this finding was consistent with a prospective study of 266 CHB patients, which showed that the levels of adiponectin increased in those with higher HBV viral load [25]. Of note, although the above mechanistic findings partially explained the viral suppression in CHB patients with concurrent fatty liver disease, current understandings remain only the tip of the iceberg.

Uncertain association between fatty liver disease and fibrosis

MAFLD is a disease with a broad spectrum from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis, and the latter may cause inflammation as well as liver fibrosis with resultant cirrhosis. In the general population, MAFLD is a known etiology for cirrhosis; however, whether concurrent MAFLD among CHB patients will aggravate fibrosis progression is inconclusive. In two studies using FibroScanTM to define fatty liver disease in CHB patients, hepatic fibrosis was positively associated with the CAP value [19,26]. In a retrospective study of 1,089 CHB patients with liver histological evaluation, patients with concurrent non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) had a higher degree of liver fibrosis [27]; consistently, steatosis was associated with fibrosis and cirrhosis in another biopsy-proven cohort of 270 CHB patients [28]. However, a large retrospective cohort study enrolling 6,786 CHB patients demonstrated a lower incidence of cirrhosis in those with fatty liver than those without, either before or after propensity score matching (PSM); the 10-year cumulative incidence was 10.5% vs. 15.5%, respectively, in the PSM cohort [29]. A meta-analysis evaluating 6,232 CHB patients from 20 studies with available histology or transient elastography data showed no association between steatosis and fibrosis (pooled odds ratio 0.87, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.54–1.39) [12]; a similar result was also demonstrated in another meta-analysis [13]. Collectively, the exact impact of MAFLD on liver fibrosis among CHB patients remains uncertain, and this may be partially attributable to the different severity of fatty liver disease in each study population, leading to a variable degree of liver injury and resultant fibrosis.

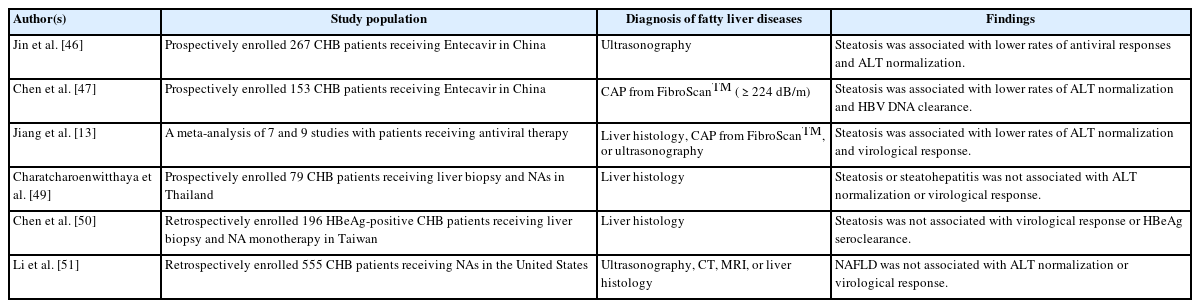

Inconclusive results for MAFLD and risk of HBV-related HCC

HCC development is one of the major adverse outcomes in patients with chronic liver diseases, including MAFLD. According to a large cohort study, the annual incidence of HCC in patients with NAFLD was 0.021%, 10-fold higher than those without liver disease [30]. However, the influence of co-existing steatosis in CHB patients remained controversial among studies (Table 1). Although MAFLD and CHB are well-established etiologies for HCC, whether concurrent MAFLD and CHB lead to a higher risk of HCC development than CHB alone is inconclusive, according to current evidence. In the prospective cohort studies with more than two-thousand male CHB patients in Taiwan, fatty liver at baseline was an independent protective factor for HCC development [20,31]. Likewise, another cohort study of 6,786 CHB patients showed a reduced 10-year risk of HCC in those with steatosis than those without steatosis, 3.74% versus 6.18%, respectively; the protective effect of steatosis remained unchanged after PSM [29]. In two recent studies conducted in Hong Kong and South Korea quantifying the degree of steatosis by FibroScanTM, a higher CAP value was associated with a lower risk of HCC occurrence in CHB populations [32,33]. Nevertheless, other studies enrolling CHB patients receiving liver biopsies demonstrated the opposite impact on HCC risk. A retrospective cohort study on a liver biopsy cohort of 270 CHB patients showed concurrent fatty liver was an independent risk factor of HCC (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 7.27, 95% CI 1.52–34.76, P=0.013) [28]; another study of 1,089 CHB patients with available liver histology found NASH was independently associated with a higher risk of HCC [27]; recently, the same cohort using the new criteria of MAFLD defined by histology revealed MAFLD was associated with poorer HCC-free survival (adjusted HR 1.93, 95% CI 1.17–3.21); however, steatohepatitis did not increase the risk of HCC among patients with MAFLD, indicating metabolic dysfunction rather than steatosis per se as the key role in the hepatocarcinogenesis [34]. A recent meta-analysis showed that the presence of fatty liver, especially biopsyproven steatosis, was associated with an increased risk of HCC in CHB patients [21].

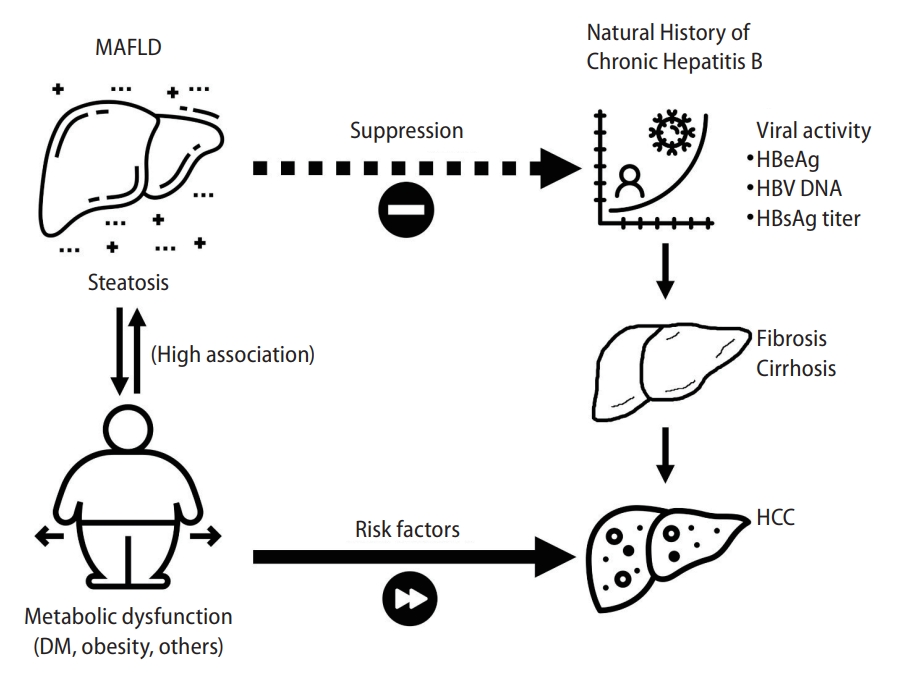

One of the plausible explanations for the above conflicting results may be the heterogeneous study populations enrolled in each study; CHB patients fulfilling the indication of the liver biopsy were expected to have higher disease severity and represented a minority among the broad disease spectrum of CHB and MAFLD, leading to the diverse results. This speculation was supported by a meta-analysis that showed no significant association between steatosis and HCC after excluding those with biopsy-proven fatty liver [21]. Another factor is the influence of the co-existing metabolic dysfunction in patients with MAFLD, including obesity or DM, which are also the established risk factors for HCC occurrence in CHB [35-37]. In other words, the simple steatosis and metabolic dysfunction required for diagnosing MAFLD may have diverse effects on hepatic carcinogenesis exclusively in CHB patients (Fig. 2) [38]. Therefore, strategies for optimal risk stratification and individualized management for those with concurrent MAFLD need to be developed in future studies.

Proposed mechanism of diverse impacts of steatosis and metabolic dysfunction on clinical outcomes of CHB. The steatosis may suppress the HBV viral activity, leading to fewer liver injuries and fibrosis, and probably a lower risk of HCC. MAFLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen.

MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

CAP for evaluation of steatosis and steatohepatitis in CHB

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis; however, the risk of internal bleeding is the primary concern in clinical practice [39]. Instead, non-invasive approaches are developed for the evaluation of fatty liver disease. Although the magnetic resonance imaging proton density fat fraction has the best accuracy among the non-invasive methods [40,41], CAP by FibroScanTM (Echosens®, Paris, France) is the point-of-care technique for the measurement of attenuation during ultrasonography to estimate the degree of steatosis with the advantages of relatively low cost and requirement in first-line clinical settings [42], and it has also been validated in patients with CHB. In a study of 366 treatment-naive CHB patients receiving liver biopsy, the accuracy of CAP for steatosis was better than those of hepatic steatosis index and ultrasonography, with the area under receiver operating characteristics curve (AUROC) up to 0.932 for histology S ≥2, although a higher overestimation rate (30.5%) was also found [43]. In another study of 65 concurrent CHB-NAFLD patients receiving liver biopsy, including 34 with NASH and 31 without NASH, the serum levels of CK-18 M30, fasting glucose, HBV DNA, and CAP were the independent predictors for NASH, and the AUROC of combining above markers reached 0.961 with a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 80.6% [44]. The usage of CAP for evaluation of steatosis is common in the CHB population; however, the performance of related modalities like the FibroScan-aspartate aminotransferase score, which predicts high-risk population in NAFLD, is uncertain in CHB patients [45]; in addition, comprehensive investigations on the association of CAP with long-term outcomes in longitudinal CHB cohorts are still to be explored.

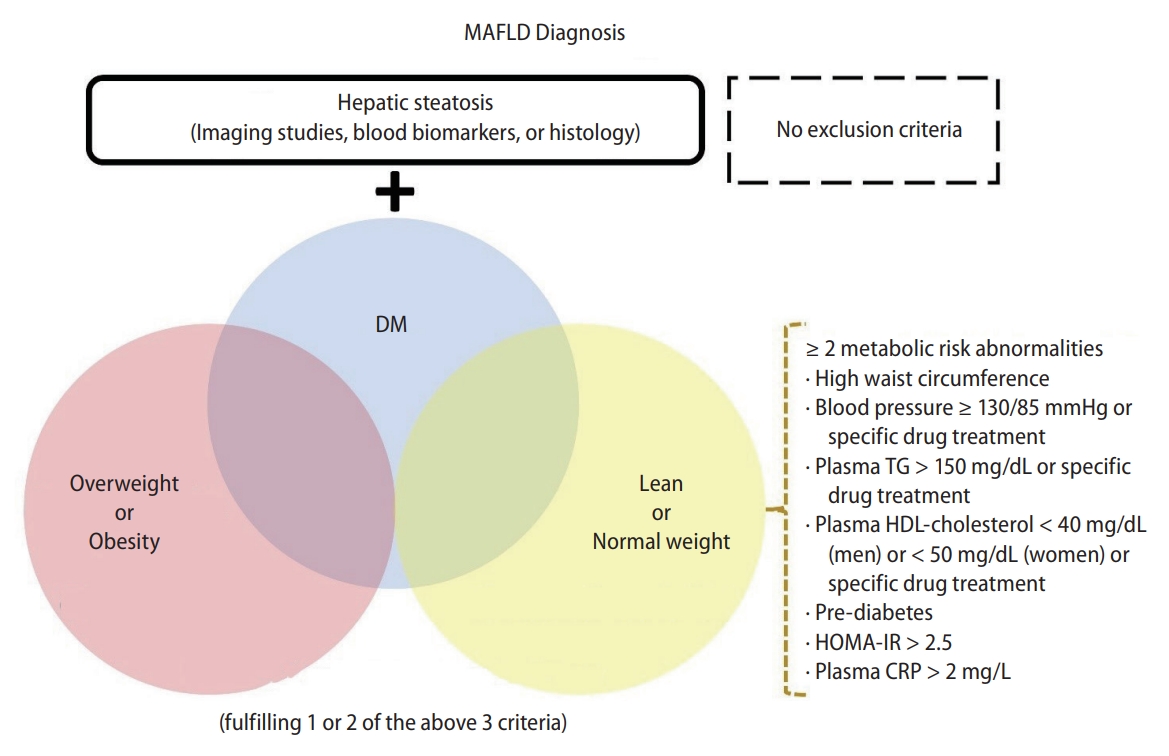

Anti-viral treatment for HBV with concurrent MAFLD

CHB is an infectious disease without effective curable treatment thus far, although the nucleot(s)ide analogues (NAs) can suppress the viral replication in patients with high viral activity. Similar treatment initiation and monitoring strategies have been proposed according to current guidelines in patients with concurrent MAFLD. However, the presence of NASH may influence the clinical assessment of viral activity and liver enzymes. In addition, some studies revealed the potential adverse impact of concurrent steatosis on the treatment efficacy using NAs (Table 2). CHB patients with hepatic steatosis receiving entecavir were found to have lower rates of serum HBV DNA undetectability and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) normalization compared to those without steatosis [46,47]. These findings were in line with two meta-analyses that showed poorer treatment responses in patients with concurrent fatty liver [13,48]. In contrast, other studies showed comparable anti-viral treatment responses regardless of steatosis [49-51]. Clinicians should pay attention to the possible interference by the concurrent hepatic steatosis since the virologic treatment response is highly associated with the long-term risk of HBV-related disease progression, including the development of HCC [52]. In patients with concurrent MAFLD, especially those with steatohepatitis, the threshold for initiation and selection of NAs should be individually evaluated; we recommend a more aggressive strategy (a lower threshold) with high-potency NAs (like tenofovir alafenamide or entecavir) for this subpopulation. For those undergoing antiviral agents, monitoring of serum ALT and HBV DNA levels and timely intervention for the poor responders are the keys to improving the prognosis in patients with concurrent MAFLD.

Prompt intervention for concurrent MAFLD in CHB

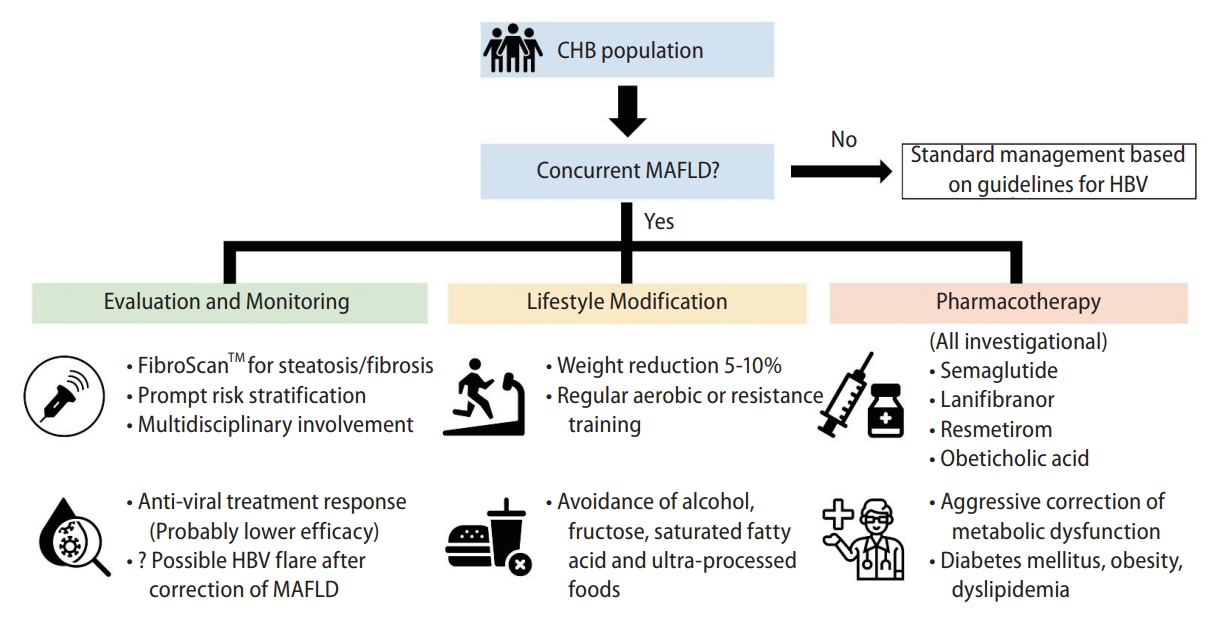

Despite the potential long-term protective effect of hepatic steatosis for HCC development in CHB patients, fatty liver is not permissive from the perspective of holistic medicine. In a cohort study of 7,761 patients using the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in the United States, those with MAFLD had a higher risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.17, 95% CI 1.04–1.32) [6]; the presence of MAFLD was also associated with increased risks of cardiovascular diseases [6,53], chronic kidney disease [54,55], and incident extrahepatic cancers [56]. As a result, active intervention for concurrent MAFLD is similarly essential for the CHB population (Fig. 3).

Proposed strategies for evaluation and management of CHB patients with concurrent MAFLD. MAFLD, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; CHB, chronic hepatitis B; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Lifestyle modifications, including enhancing exercise and diet control, are the core of effective therapy, and body weight reduction is the goal and indicator for any intervention [57]. According to current evidence, weight loss of 5–10% by a hypocaloric diet (1,200–1,500 kcal per day), avoidance of alcohol, fructose, saturated fatty acid or ultra-processed foods, and regular exercise (either aerobic or resistance training) are practical approaches in daily practice [57-60]. Although direct evidence from prospective studies to confirm the efficacy of lifestyle modification in CHB patients with concurrent MAFLD is lacking, patient education about the above points is still recommended due to the significant benefits proven in the general population.

The standard pharmacological therapy for steatohepatitis has not been established yet, but several promising agents are now in clinical trials. Semaglutide, one of the glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, showed its superiority in NASH resolution over placebo in a 72-week, double-blind phase 2 trial enrolling patients with histology-confirmed NASH and fibrosis, although it failed to achieve regression in fibrosis stage [61]. Lanifibranor, a pan-peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonist, achieved the endpoints of resolution of NASH and reversal of fibrosis compared with placebo in phase II double-blind, randomized trial [62]. Other potential candidates for effective steatohepatitis treatment include resmetirom, a selective thyroid hormone receptor-β agonist [63,64], and obeticholic acid, the selective farnesoid X receptor agonist [65-67]. Of note, participants with CHB were excluded from the above trials. Further investigations of these agents aiming at the CHB subpopulation with concurrent steatohepatitis are urgently needed.

Another issue that should be noted is whether the correction of hepatic steatosis will cause an increase in HBV replicative activity. As mentioned previously, the inverse correlation between hepatic steatosis and viral activity is evident, but the exact mechanisms and the causal relationship are still unknown, which means there is no clear recommendation for CHB patients with hepatic steatosis undergoing correction of metabolic derangement. We recommend a short-interval monitoring plan which includes the blood test for ALT levels (with or without HBV viral load) every three months during the correction. The optimal strategy warrants more clinical and mechanistic studies.

Aggressive correction of metabolic dysfunction in CHB patients

Factors of metabolic dysfunction like DM, obesity, or dyslipidemia are the essential components for MAFLD [68], and they are also well-established risk factors of fibrosis progression and HCC development among CHB patients. In a prospective study of 663 treatment-naïve CHB patients with serial liver stiffness measurements, metabolic syndrome, central obesity, and low level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol were independently associated with liver fibrosis progression regardless of the change in viral load and ALT levels [69]. The adverse influence was recently confirmed even in those receiving anti-viral treatment. In a large cohort study based on population-wide data from Taiwan and Hong Kong, the presence of DM was one of the reliable risk score variables to predict HCC occurrence in CHB patients receiving entecavir or tenofovir [36]. In a prospective study of 5,754 CHB patients receiving NA in China, central obesity was associated with a two-fold risk of HCC before and after PSM [37]. Among patients with confirmed MAFLD, the additive metabolic risk abnormalities, especially DM, are known to be associated with higher cardiovascular, cancer, and all-cause mortality [70]. Similarly, in a recent Korean nationwide cohort study of 317,856 CHB patients, the metabolic risk factor burden increased the risks of HCC, non-HCC cancers, and all-cause mortality in a dose-dependent manner [71]. Unlike steatosis, these metabolic risk factors seem to independently facilitate fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis without the interaction with HBV activity, so the aggressive correction of them is the key to better prognosis in both CHB and the general population regardless of the presence of steatosis.

Unsolved questions

A few issues must be addressed to optimize management in patients with concurrent CHB and MAFLD. First, considering the heterogeneous subpopulation within the MAFLD criteria, a better risk stratification strategy is required; those with different types of metabolic dysfunction may have distinct clinical characteristics and prognoses, and the impacts of these factors may be additive. For example, the presence of both DM and obesity should strengthen the indication for a more intensive follow-up schedule compared to those with only one or no metabolic risk factor. Second, since the concurrent steatosis leads to potential suppression of viral activity and resultant hepatocarcinogenesis in CHB, whether the simple steatosis alone (without other systemic risk factors of metabolic dysfunction) is tolerable or even favorable in the specific population such as CHB patients warrants more clinical studies to conclude. Third, how the therapeutic candidates for MAFLD, like GLP-1 agonist, influence the disease course and prognosis of CHB is still being determined due to the exclusion by trials and should be answered by the following real-world or post-marketing clinical trial data in the future.

CONCLUSIONS

Since the re-definition of MAFLD, in patients with CHB, several unsolved issues from mechanistic interaction to medical approaches warrant future investigations. Exploration of the mechanisms of the inverse correlation between steatosis and viral activity will help understand HBV virology which may be necessary for developing effective pharmacotherapy for HBV. Well-designed clinical trials focusing on optimal treatments for CHB patients with concurrent MAFLD are needed. As the increasing disease burden of metabolic syndrome worldwide, appropriate and timely action with multidisciplinary integration based on updated evidence will pave the way to the ultimate goal of enhancing prognosis and quality of life for the CHB population.

Notes

Authors’ contribution

Review design: Huang SC, Liu CJ. Analysis and interpretation of papers: Huang SC, Liu CJ. Drafting of the manuscript: Huang SC. Critical revision of the review: Liu CJ.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support from the National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW), Taiwan.

Abbreviations

MAFLD

metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

CHB

chronic hepatitis B

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

HBV

hepatitis B virus

NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

HBeAg

hepatitis B e antigen

HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

CAP

controlled attenuation parameter

HBcAg

hepatitis B core antigen

siRNA

small interfering RNA

NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

PSM

propensity score matching

OR

odds ratio

CI

confidence interval

HR

hazard ratio

AUROC

area under receiver operating characteristics curve

NA

nucleot(s)ide analogue

ALT

alanine aminotransferase

GLP-1

glucagon-like peptide 1

LSM

liver stiffness measurements

HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

CT

computed tomography

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging