| Clin Mol Hepatol > Volume 30(1); 2024 > Article |

|

See the commentary-article "Evaluation of the histological scoring systems of autoimmune hepatitis: A significant step towards the optimization of clinical diagnosis" on page 157.

ABSTRACT

Background/Aims

The histological criteria in the 1999 and 2008 scoring systems proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) have their inherent limitations in diagnosing autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). In this study, we evaluated the histology components of four scoring systems (1. revised original scoring system [ŌĆ£1999 IAIHGŌĆØ], 2. simplified scoring system [ŌĆ£2008 IAIHGŌĆØ], 3. modified histologic criteria [ŌĆ£2017 UCSFŌĆØ], and 4. a new histologic criteria proposed by the International AIH Pathology Group [ŌĆ£2022 IAHPGŌĆØ]) in AIH patients.

Methods

Medical records and liver biopsies were retrospectively reviewed for 68 patients from two independent medical institutions, diagnosed with AIH based on the 1999 IAIHG system between 2006 and 2016. The histological features were reviewed in detail, and the four histological scoring systems were compared.

Results

Out of the 68 patients, 56 (82.4%) patients met the ŌĆ£probableŌĆØ or ŌĆ£definiteŌĆØ AIH criteria of the 2008 IAIHG system, and the proportion of histologic score 2 (maximum) was 40/68 (58.8%). By applying the 2017 UCSF criteria, the number of histology score 2 increased to 60/68 (88.2%), and ŌĆ£probableŌĆØ or ŌĆ£definiteŌĆØ AIH cases increased to 61/68 (89.7%). Finally, applying the 2022 IAHPG histology score resulted in the highest number of cases with histologic score 2 (64/68; 94.1%) and with a diagnosis of ŌĆ£probableŌĆØ or ŌĆ£definiteŌĆØ AIH (62/68; 91.2%).

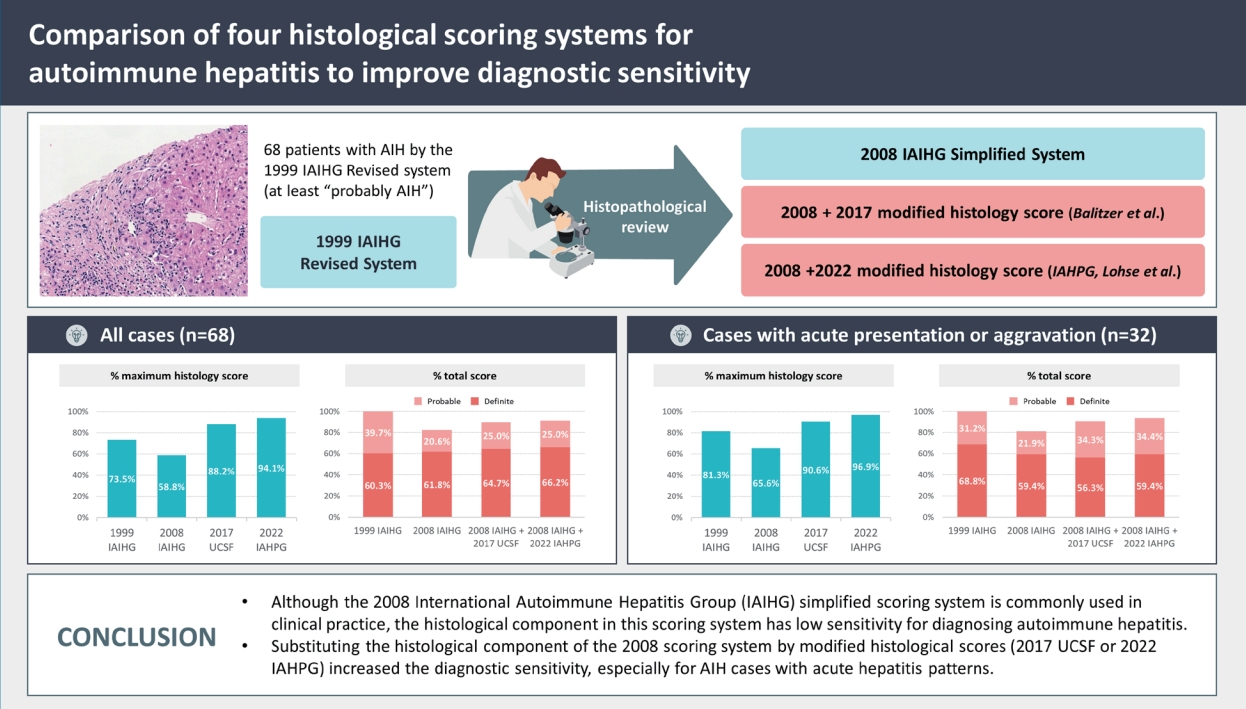

Graphical Abstract

The diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis(AIH) is made based on the clinical presentation, laboratory findings (e.g., elevated liver enzymes, serum immunoglobulin G [IgG], and the presence of autoantibodies), the histopathological findings, and the exclusion of other etiologies [1]. The diagnosis of AIH can at times be difficult considering the heterogeneity of the clinical features and the large number of differential diagnoses [2]. Diagnostic scoring systems have been proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG)ŌĆöoriginally in 1993, revised in 1999 and then simplified in 2008ŌĆöwith the initial aim of selecting a homogeneous group of AIH patientsfor research [3-5]. These scoring systems have eventually made their way into clinical practice, and the revised criteria (hereafter referred to as ŌĆ£1999 IAIHGŌĆØ) and the simplified criteria (hereafter referred to as ŌĆ£2008 IAIHGŌĆØ) are commonly used in routine clinical care [3,4].

Liver biopsy is an essential part of the diagnosis of AIH, and this is reflected in the histology components of the 1999 IAIHG and 2008 IAIHG systems [3,4,6]. For example, in the 2008 IAIHG system, in which a minimum of 6 points is necessary to call a case as at least ŌĆ£probableŌĆØ AIH, liver histology is allocated up to 2 out of a total of 8 points [4]. However, the histological criteria stated in this system has not been prospectively validated, and the diagnostic utility of hepatocyte rosette formation and emperipolesis has been questioned [7,8]. To this end, modificationsin the his tological component of the 2008 IAIHG criteria have been recently proposed by pathologists [7,8]. In 2017, Balitzer et al. [7] proposed a modified histological criteria for AIH (hereafter referred to as ŌĆ£2017 UCSFŌĆØ), based on the necroinflammatory activity and the degree of plasma cell infiltration, and excluding rosettes and emperipolesis. This modified histologic criteria increased the histology score for AIH cases, and applying the 2017 UCSF histologic criteria to the 2008 IAIHG system increased the diagnostic sensitivity of AIH [7]. Recently, a group of liver pathologists(International Autoimmune Hepatitis Pathology Group) published a consensus statement for the histological diagnosis of AIH (hereafter referred to asŌĆ£2022 IAHPGŌĆØ) [8].

In this study, we compared the four scoring systemsŌĆö1999 IAIHG, 2008 IAIHG, 2008 IAIHG with 2017 UCSF histology criteria (2008 IAIHG+2017 UCSF), and 2008 IAIHG with 2022 IAHPG criteria (2008 IAIHG+2022 IAHPG)ŌĆöin a retrospective cohort of AIH patientsfrom two institutionsin Korea.

Liver biopsy cases diagnosed between 2006 and 2016 at Seoul National University Hospital and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital were retrieved from the pathology database of each institution, by searching the keyword ŌĆ£autoimmune hepatitisŌĆØ in pathology reports. Cases containing the terms ŌĆ£typical AIHŌĆØ, ŌĆ£consistent with AIHŌĆØ, ŌĆ£suggestive of AIHŌĆØ, and ŌĆ£the possibility of AIH could be consideredŌĆØ were included in the search. The medical records for each patient were reviewed and the following information was recorded: age, sex, body massindex (BMI), viral hepatitisstatus, alcohol consumption history, medication history, symptoms at initial presentation, biochemical status at the time of biopsy, serum IgG level, the presence of auto-antibodies (antinuclear antibody [ANA], anti-smooth muscle antibody [SMA], anti-liver kidney microsome [LKM] type1 antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody [AMA]), co-morbidities, and extrahepatic autoimmune disorders including Sj├Čgren syndrome and autoimmune thyroiditis. Cases with other etiologies (e.g., alcoholic hepatitis, viral hepatitis, toxic hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis), overlap syndrome and those with uncertain etiology were excluded. Liver biopsies with fewer than 6 portal tracts were excluded. The disease course and response to immunosuppressive therapy were also evaluated. Complete response was defined as the normalization of serum transaminase and immunoglobulin levels below the upper normal limit within 6 months of initial treatment. Finally, 68 patients with a final diagnosis of AIH based on the clinical features, laboratory findings and pathology were included in the study. All cases were interpreted as ŌĆ£definiteŌĆØ or ŌĆ£probableŌĆØ AIH, based on the pretreatment aggregates scores of the 1999 IAIHG system [3]. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital and Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (#H-2208-098-1350), and informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Hematoxylin and eosin and Masson trichrome-stain slides of liver biopsies were reviewed by two liver pathologists (S.A and H.K). The necroinflammatory grade was determined for each case using the Ishak grading scheme as follows: interface activity (A0-A4), confluent necrosis (B1-B6), lobular necroinflammatory activity (C0-C4), and portal inflammation (D0-D4) [7,9]. The degree of fibrosis was recorded using the Batts-Ludwig scheme (scale 0-4) [7,10]. The presence of hepatocyte rosettes, emperipolesis, and the predominant inflammatory cells were evaluated. Rosettes were defined as hepatocytes arranged around a clearly identifiable luminal space [7]. Emperipolesis was defined as the presence of lymphocytes or plasma cells within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes [7]. A plasma cell cluster was defined as an aggregate of more than 5 plasma cells in one focus [7]. The presence of bile duct injury, bile duct loss and steatosis were also evaluated. The histological features were reviewed independently, without knowledge of the other pathologistŌĆÖs interpretation results, and after completing the first round of independent histopathological slide review, discrepant cases were reviewed together at a multiheaded microscope.

For each case, the histology scores of the 1999 IAIHG system (maximum 5 points) and 2008 IAIHG system (maximum 2 points) were calculated [3,4]. We then evaluated the modified histology scores of the 2017 UCSF and 2022 IAHPG proposals [7,8]. The four scoring systems are summarized in Table 1. For the 2022 IAHPG system, we categorized ŌĆ£likely AIHŌĆØ as 2 points, ŌĆ£possible AIHŌĆØ as 1 point and ŌĆ£unlikely AIHŌĆØ as 0 point, and applied these scoresto the 2008 IAIHG system.

The clinical features of the 68 patients are summarized in Table 2. All patients were Korean and 55 (80.9%) were female. The mean age at the time of diagnosis was 58 years (range: 20ŌĆō87), and 16 (23.5%) patients had BMI >25 kg/m2. Thirty-two (47.1%) patients presented with acute presentation or aggravation. Thirty-six (52.9%) patients were symptomatic at the time of diagnosis (including jaundice, nausea, and abdominal discomfort), and one (1.5%) patient displayed hepatic decompensation. Serum IgG levels were elevated in 53 (77.9%) patients, and ANA was detected in 65 (95.6%) cases. Three patients with ANA negativity showed increased serum IgG levels. Anti-SMA was detected in 20 (35.1%) out of 57 tested patients, and anti-LKM type 1 antibody was negative in all 33 tested patients. All patients were negative for AMA.

Sixteen patients also had extrahepatic autoimmune disease, including Sj├ČgrenŌĆÖs syndrome (11.8%), systemic lupus erythematosus (7.4%), rheumatoid arthritis (1.5%), polymyositis (1.5%), and autoimmune thyroid disease (1.5%). All patients were treated with immunosuppressive therapy: the initial treatment was prednisolone for 52 (76.5%) patients, and prednisolone and azathioprine for 16 (23.5%) patients. Out of the 66 patients with available follow up information, 53 (80.3%) patients showed complete response to initial treatment, and 13 (19.7%) showed incomplete response for initial treatment. Glucocorticoid-induced side effects were identified in 20 (30.3%) patients. Co-morbidities included hypertension (35.3%), diabetes mellitus(13.2%), and osteoporosis(35.3%).

The histopathological features of 68 patients are summarized in Table 3. Sixty-three (92.6%) cases showed at least moderate portal activity (ŌēźD2), and 60 (88.2%) cases demonstrated at least mild/moderate interface activity (ŌēźA2) (Fig. 1A). Confluent necrosis (ŌēźB2) was identified in 27 (39.7%) cases. Lobular necroinflammatory activity (ŌēźC2) was observed in 65 (95.6%) cases. Fibrosis of any degree was present in 65 (95.6%) cases. Bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis was observed in 15 (22.1%) and 16 (23.5%) patients, respectively. The predominant inflammatory cell type was lymphoplasmacytic in 60 (88.2%) cases, and lymphocytic in 8 (11.8%) cases. None of the cases showed predominant neutrophilic or eosinophilic infiltration. At least one plasma cell was present in the portal tracts of all but one case, and plasma cell clusters in the portal tracts were identified in 51 (75.0%) patients. Lobular plasma cell infiltration was observed in 59 (86.8%) patients. Emperipolesis and hepatocellular rosettes were identified in 49 (72.1%) and 50 (73.5%) cases, respectively (Fig. 1B, C). Co-existing steatosis was identified in 18 (26.5%); 18 of these cases showed mild macrovesicular steatosis and one case demonstrated moderate macrovesicular steatosis. Perivenular and perisinusoidal fibrosis was identified in 3 (4.4%) and 2 (2.9%) cases, respectively. None of the cases demonstrated features of steatohepatitis. Bile duct damage of more than mild degree was identified in 3 (4.4%) cases; however, bile duct loss was not observed in any patient.

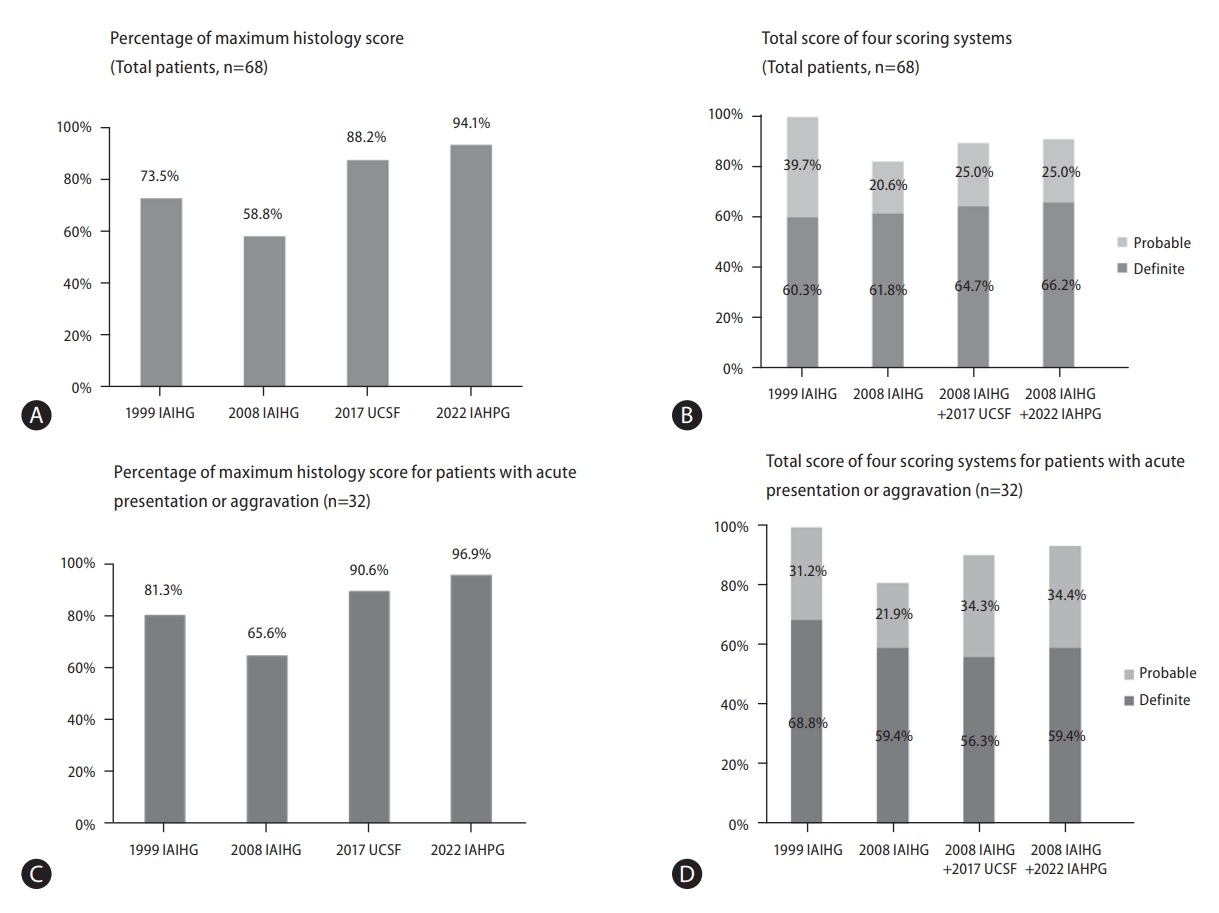

Based on the clinical and histological findings of each case, the AIH scores were calculated using the four different scoring methods. The results are summarized in Figure 2A, 2B and Table 4. For the 1999 IAIHG (revised original scoring system), the pretreatment criteria was applied. All patients met the definite or probable criteria by the 1999 IAIHG system (60.3% ŌĆ£definiteŌĆØ, 39.7% ŌĆ£probableŌĆØ). The histologic score component ranged from 0 to 5 (the maximum histology score) with a mean value of 4.43. By this system, 50 (73.5%) cases were given the maximum histologic score (5).

Using the 2008 IAIHG system, 56 (82.4%) cases met the probable (total score Ōēź6) or definite (Ōēź7) criteria for AIH (61.8% ŌĆ£definiteŌĆØ, 20.6% ŌĆ£probableŌĆØ). The histological scores were ŌĆ£1ŌĆØ for 28 (41.2%) and ŌĆ£2ŌĆØ for 40 (58.8%) cases, and the mean score was 1.59.

By applying the 2017 UCSF system to the 2008 IAIHG system (2008 IAIHG+2017 UCSF), the number of casesthat qualified for the maximum histology score (ŌĆ£2ŌĆØ) increased from 40 (58.8%) to 60 (88.2%) cases, and the mean histologic score increased from 1.59 to 1.87. Accordingly, when the 2017 UCSF histology criteria was applied to the histology component of the 2008 IAIHG system, the number of cases that met the definite or probable criteria for AIH increased to 61 (89.7%), with an increase of ŌĆ£definiteŌĆØ casesfrom 61.8% to 64.7%.

Finally, by the recently proposed 2022 IAHPG criteria (2008 IAIHG+2022 IAHPG), the number cases that qualified for the maximum histology score (ŌĆ£2ŌĆØ) was the highest at 64 (94.1%) cases, with the highest mean histologic score of 1.94. By applying the 2022 IAHPG criteria to the 2008 system, 62 (91.2%) cases met the probable or definite criteria for AIH, with 45 (66.2%) cases being classified as ŌĆ£definite AIHŌĆØ. The proportion of definite AIH (total score Ōēź7) was the highest among fourscoring systems.

For the thirty-two cases with acute presentation or aggravation, 21 (65.6%) cases met the probable or definite AIH category by 2008 IAIHG system (Table 5). However, by applying 2017 UCSF system, the number of cases that qualified for the maximum histology score (ŌĆ£2ŌĆØ) increased from 21 (65.6%) to 29 (90.6%) cases, and there was an increase in cases that met the probable or definite AIH category from 81.3% to 90.6%. Finally, by applying 2022 IAHPG system, the number of cases with the maximum histology score was the highest (96.9%), and the proportion of probable or definite AIH category was the highest (93.8%) (Fig. 2C, D).

Although the 1999 IAIHG scoring system is regarded as the gold standard for the diagnosis of AIH, it was originally intended for research purposes and is too complicated to use in everyday clinical practice. To this end, the Simplified criteria was proposed in 2008 to provide a diagnostic criteria that was easier to use; however, it has been recognized that the histology component of the 2008 IAIHG system may lead to underscoring of potential AIH cases, and proposals have been put forth to increase the diagnostic sensitivity of this system [7,8,11-14]. In this retrospective study, we compared four AIH scoring systems in 68 Korean patients who were diagnosed as AIH based on the 1999 IAIHG system, and focused on the histological score component. As expected, the 2008 IAIHG system showed the lowest sensitivity (82.4% for ŌĆ£Probable or definite AIHŌĆØ) among the fourscoring systems.

By substituting the histological criteria of the 2008 IAIHG system with the 2022 IAHPG histologic score, the sensitivity of diagnosing ŌĆ£definite AIHŌĆØ and ŌĆ£at least probable AIHŌĆØ increased from 61.8% and 82.4%, respectively (2008 IAIHG) to 66.2% and 91.2%, respectively (2008 IAIHG+2022 IAHPG). When the histological component was analyzed separately, the proportion of cases with the maximum histological scores was highest by the 2022 IAHPG method (94.1%), and lowest by the 2008 IAIHG system (58.8%).

Liver biopsy is an essential component in making a diagnosis of AIH, and each AIH scoring system accordingly contains a histology score [6]. The 1999 IAIHG system emphasizes the importance of moderate/severe interface hepatitis (3 points out of a maximum of 5 histology points), and the total histology score is the result of a simple addition of component scores. Therefore, compared to the 2008 system in which potential AIH cases without hepatocytic rosettes or emperipolesis are regarded insufficient for a diagnosis of ŌĆ£typicalŌĆØ AIH, such cases could qualify for a diagnosis of ŌĆ£definite AIHŌĆØ by the 1999 system as long as other clinical or pathological features are present, yielding a total score of >15 points. In this regard, the 1999 IAIHG system is more sensitive compared to the 2008 IAIHG system. However, both IAIHG systems do not take into account the acute hepatitis presentation of AIH; indeed, the histological features of AIH vary according to disease status, and do not always demonstrate the classical feature of a chronic hepatitis patternwith portal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration and interface hepatitis [15,16]. AIH with acute presentation mostly demonstrates histological features of acute lobular hepatitis, and such cases would be less likely to meet the histological criteria for AIH according to the 1999 and 2008 IAIHG systems, due to the lack of interface hepatitis. In fact, acute hepatitis patterns of AIH are being increasingly recognized, and the differential diagnosis between AIH and other causes of acute hepatitis, such as acute viral hepatitis and drug/toxin-induced liver injury, is often difficult but at the same time, very important [15,17]. It is therefore crucial for pathologists to be aware of this type of AIH, and applying the 2022 IAHPG definitions for the lobular hepatitis pattern of AIH would serve as a useful guiding tool in identifying the acute form of AIH [8].

For the 2008 IAIHG ŌĆ£simplified scoringŌĆØ system, the histological score accounts for a maximum of 2 out of 8 points [4]. A histological score of ŌĆ£2ŌĆØ requires the presence of interface hepatitis and hepatocytic rosettes and emperipolesis, and if any one of these features are absent, a score of 1 is given for a chronic hepatitis picture [4]. However, recent studies have questioned the utility of including hepatocytic rosettes and emperipolesis as prerequisites for a diagnosis of ŌĆ£typicalŌĆØ AIH [7,18]. The reported frequency of hepatocyte rosette formation and emperipolesis has markedly varied, with ranges of 19ŌĆō75% and 19ŌĆō80%, respectively [7,15,18-22]. They are difficult to interpret in daily diagnostic practice; identifying emperipolesis, especially, is a time-consuming task for pathologists, and also prone to interobserver variability in interpretation. Moreover, hepatocytic rosettes and emperipolesis lack sensitivity and specificity for AIH, as hepatocyte rosettes are seen in during regeneration after various types of injury, and emperipolesis is seen in severe lobular injury [7,18,20,21]. Thus, these two histological features were excluded from the 2017 UCSF and 2022 IAHPG histology scores [7,8].

The presence of hyaline globules in Kupffer cells has been suggested to serve as a diagnostic clue for AIH, and a modification of the 2008 IAIHG histology component has been proposed by Gurung et al., which requires the presence of Kupffer cell hyaline globules in addition to a prominent plasmacytic infiltration to qualify as a ŌĆ£typicalŌĆØ AIH [23]. However, this needs further validation; a few other studies demonstrated that this feature was not correlated with serum IgG levels, autoantibody status or histological activity/fibrosis, and moreover, its identification requires additional stains such as periodic acid-Schiff post-diastase (D-PAS) stain and CD68 [24,25]. Another interesting finding which requires further validation is the higher number of apoptotic lymphocytes in portal tractsin AIH compared to other liver diseases [26].

The limitations of this study are as follows. It is a retrospective study from two institutions on a relatively small number of cases. In addition, a control group with other etiologies was not included, and only typical cases confirmed by the 1999 IAIHG system were included in thisstudy. Therefore, the specificity of each diagnostic system was not assessed. Nevertheless, this is a uniform cohort of Korean AIH patients and, to our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare the histological scoring systems, including the most recent 2022 IAHPG consensus criteria.

In summary, recently proposed 2017 UCSF and 2022 IAHPG criteria increased the histological scores of AIH cases, and substituting the histological component of the 2008 IAIHG system with these newly proposed histological criteria increased the diagnostic sensitivity for AIH. Therefore, the recently proposed histologic criteria are expected to resolve the low diagnostic sensitivity of 2008 simplified scoring system, which warrantsfurther investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the research fund of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (SNUBH 02-2018-011, S.A.) and The Research Supporting Program of The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver and The Korean Liver Foundation (H.K.).

FOOTNOTES

AuthorsŌĆÖ contributions

Conception: H.K., S-H.J.; Data acquisition: S.A., S-H.J., EJ.C., K.L., G.K., H.K.; Data Analysis: S.A., H.K.; Interpretation: S.A.,EJ.C., H.K. S-H.J.; Original Draft: S.A.; Critical revision: H.K. S-H.J. All authors approved for submission of the final version of the manuscript.

Figure┬Ā1.

Representative histologic images of autoimmune hepatitis. (A) Interface hepatitis with dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltration. (B) Emperipolesis (arrow) is defined as the presence of lymphocytes or plasma cells within the cytoplasm of hepatocytes. (C) Hepatocyte rosettes (arrows) are defined as hepatocytes arranged around a clearly identifiable luminal space. All images are from hematoxylin and eosin stained slides at 200x magnification.

Figure┬Ā2.

Validation of autoimmune hepatitis scoring systems. (A) Percentage of maximum histology score for total patients (n=68). By 1999 IAIHG criteria, 73.5% of cases were given the maximum histologic score (*maximum score: 5). The proportion of cases with the maximum histological scores were lowest by the 2008 IAIHG system (58.8%), and highest by the 2022 IAHPG method (94.1%). (B) Total score of four scoring systems for total patients (n=68). All patients met ŌēźŌĆ£Probable AIHŌĆØ criteria by the 1999 IAIHG system. In contrast, 82.4% of patients met ŌēźŌĆ£Probable AIHŌĆØ of the 2008 IAIHG system. However, substituting UCSF and IAHPG histologic criteria to the 2008 IAIHG system resulted in increased sensitivity for diagnosing AIH (ŌēźŌĆ£Probable AIHŌĆØ) from 82.4% to 89.7% and 91.2%, respectively. (C) Percentage of maximum histology

score for patients with acute presentation or aggravation, n=32). By the 1999 IAIHG criteria, 81.3% of cases were given the maximum histologic score (*maximum score: 5). The proportion of cases with the maximum histological scores were lowest by the 2008 IAIHG system (65.6%), and highest by applying the 2022 IAHPG method (96.9%). (D) Total score of four scoring systems for patients with acute presentation or aggravation, n=32). All patients met ŌēźŌĆ£Probable AIHŌĆØ criteria by the 1999 IAIHG system. In contrast, 81.3% of patients met ŌēźŌĆ£Probable AIHŌĆØ of the 2008 IAIHG system. However, substituting UCSF and IAHPG histologic criteria to the 2008 IAIHG system resulted in increased sensitivity for diagnosing AIH (ŌēźŌĆ£Probable AIHŌĆØ) from 81.3% to 90.6% and 93.8%, respectively. IAIHG, international autoimmune hepatitis group; IAHPG, international

autoimmune hepatitis pathology group; AIH, autoimmune hepatitis.

Table┬Ā1.

Histological criteria in the four scoring systems

| 1999 IAIHG | 2008 IAIHG | 2017 UCSF |

2022 IAHPG |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Portal hepatitis |

Lobular hepatitis |

|

| Histology score (2) (ŌĆ£typicalŌĆØ) | Histology score (2) | Likely AIH (2) | Likely AIH (2) | |

| - Interface hepatitis (moderate/severe) +3 | 1) Interface hepatitis with portal | Hepatitic picture with any of the following: | Portal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate + one/both of: | More than mild lobular hepatitis + at least one of: |

| - Predominantly lymphocytic infiltrate +1 | lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates extending into lobules | 1) Plasma cells (numerous/clusters) | 1) >mild interface hepatitis | 1) Lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates |

| - Hepatocyte rosettes +1 | 2) Emperipolesis | 2) High necroinflammatory activity (interface activity ŌēźA3* and/or confluent necrosis ŌēźB2 and/or lobular activity ŌēźC3) | 2) >mild lobular inflammation | 2) Interface hepatitis |

| - None of the above -5 | 3) Hepatocytic rosettes | - in the absence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease | 3) Portal-based fibrosis | |

| - Biliary changes -3 | - in the absence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease | |||

| - Other changes -3 | ||||

| Histology score (1) (ŌĆ£compatibleŌĆØ) | Histology score (1) | Possible AIH (1) | Possible AIH (1) | |

| Picture of chronic hepatitis with lymphocytic infiltration without all 3 of the above features | 1) Hepatitis with mild/moderate necroinflammatory activity with any of the following: | Portal lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate | Any lobular hepatitis | |

| - without either of the likely features 1 or 2 above, | - without any of the likely features 1-3 above | |||

| a) Interface activity A2 | - in the absence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease | - in the absence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease | ||

| b) Confluent necrosis B1 | OR | OR | ||

| c) Lobular activity C2 | - with one/both of the likely features above | - with any of the likely features above | ||

| 2) Copper and CK7 stains negativeŌĆĀ | - in the presence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease | - in the presence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease | ||

| Histology score (0) (ŌĆ£atypicalŌĆØ) | Histology score (0) | Unlikely AIH (0) | Unlikely AIH (0) | |

| Features suggestive of other diagnoses | Features not observed in AIH: | Portal hepatitis | Any lobular hepatitis | |

| - Florid bile duct lesions | - without either of the likely features above | - without any of the likely features above | ||

| - Bile duct loss | - in the presence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease | - in the presence of histological features suggestive of another liver disease | ||

| - Copper/CK7 positivityŌĆĀ | ||||

Table┬Ā2.

Clinical features of the patients in this study (n=68)

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| ŌĆāMale | 13 (19.1) |

| ŌĆāFemale | 55 (80.9) |

| Age (yr) | 58 (20ŌĆō87) |

| Body mass index, >25 kg/m2 | 16 (23.5) |

| Acute presentation or aggravation | 32 (47.1) |

| Symptom | |

| ŌĆāAsymptomatic | 31 (45.6) |

| ŌĆāSymptomatic | 36 (52.9) |

| ŌĆāDecompensation | 1 (1.5) |

| Increased Ig G level | 53 (77.9) |

| ANA positivity | 65 (95.6) |

| Initial treatment | |

| ŌĆāPrednisolone | 52 (76.5) |

| ŌĆāPrednisolone and azathioprine | 16 (23.5) |

| Other autoimmune disease | |

| ŌĆāSj├ČgrenŌĆÖs syndrome | 8 (11.8) |

| ŌĆāSystemic lupus erythematosus | 5 (7.4) |

| ŌĆāRheumatoid arthritis | 1 (1.5) |

| ŌĆāPolymyositis | 1 (1.5) |

| ŌĆāAutoimmune thyroid disease | 1 (1.5) |

| Other disease | |

| ŌĆāHypertension | 24 (35.3) |

| ŌĆāDiabetes | 9 (13.2) |

| ŌĆāOsteoporosis | 24 (35.3) |

| ŌĆāDepression or panic order | 2 (2.9) |

| ŌĆāMalignancy | 4 (5.9) |

| Treatment response* | |

| ŌĆāResponse | 53 (80.3) |

| ŌĆāIncomplete response | 13 (19.7) |

| Steroid-induced side effects* | 20 (30.3) |

Table┬Ā3.

Histopathological features (n=68)

Table┬Ā4.

Validation of autoimmune hepatitis scoring systems for total patients (n=68)

Table┬Ā5.

Validation of autoimmune hepatitis scoring systems for patients with acute presentation or aggravation (n=32)

REFERENCES

1. Heo NY, Kim H. Epidemiology and updated management for autoimmune liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2023;29:194-196.

2. Manns MP, Lohse AW, Vergani D. Autoimmune hepatitis--Update 2015. J Hepatol 2015;62(1 Suppl):S100-S111.

3. Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, Bianchi L, Burroughs AK, Cancado EL, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 1999;31:929-938.

4. Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, Par├®s A, Dalekos GN, Krawitt EL, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2008;48:169-176.

5. Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG. Meeting report: International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Hepatology 1993;18:998-1005.

6. Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL). KASL clinical practice guidelines for management of autoimmune hepatitis 2022. Clin Mol Hepatol 2023;29:542-592.

7. Balitzer D, Shafizadeh N, Peters MG, Ferrell LD, Alshak N, Kakar S. Autoimmune hepatitis: review of histologic features included in the simplified criteria proposed by the international autoimmune hepatitis group and proposal for new histologic criteria. Mod Pathol 2017;30:773-783.

8. Lohse AW, Sebode M, Bhathal PS, Clouston AD, Dienes HP, Jain D, et al. Consensus recommendations for histological criteria of autoimmune hepatitis from the International AIH Pathology Group: Results of a workshop on AIH histology hosted by the European Reference Network on Hepatological Diseases and the European Society of Pathology: Results of a workshop on AIH histology hosted by the European Reference Network on Hepatological Diseases and the European Society of Pathology. Liver Int 2022;42:1058-1069.

9. Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol 1995;22:696-699.

10. Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis. An update on terminology and reporting. Am J Surg Pathol 1995;19:1409-1417.

11. Hennes EM, Oo YH, Schramm C, Denzer U, Buggisch P, Wiegard C, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil as second line therapy in autoimmune hepatitis? Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:3063-3070.

12. Wiegard C, Schramm C, Lohse AW. Scoring systemsfor the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis: past, present, and future. Semin Liver Dis 2009;29:254-261.

13. Gatselis NK, Zachou K, Koukoulis GK, Dalekos GN. Autoimmune hepatitis, one disease with many faces: etiopathogenetic, clinico-laboratory and histological characteristics. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:60-83.

14. Yeoman AD, Westbrook RH, Al-Chalabi T, Carey I, Heaton ND, Portmann BC, et al. Diagnostic value and utility of the simplified International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) criteria in acute and chronic liver disease. Hepatology 2009;50:538-545.

15. Iwai M, Jo M, Ishii M, Mori T, Harada Y. Comparison of clinical features and liver histology in acute and chronic autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatol Res 2008;38:784-789.

16. Washington MK. Autoimmune liver disease: overlap and outliers. Mod Pathol 2007;20 Suppl 1:S15-30.

17. Tsutsui A, Harada K, Tsuneyama K, Nguyen Canh H, Ando M, Nakamura S, et al. Histopathological analysis of autoimmune hepatitis with ŌĆ£acuteŌĆØ presentation: Differentiation from drug-induced liver injury. Hepatol Res 2020;50:1047-1061.

18. Gurung A, Assis DN, McCarty TR, Mitchell KA, Boyer JL, Jain D. Histologic features of autoimmune hepatitis: a critical appraisal. Hum Pathol 2018;82:51-60.

19. Miao Q, Bian Z, Tang R, Zhang H, Wang Q, Huang S, et al. Emperipolesis mediated by CD8 T cells is a characteristic histopathologic feature of autoimmune hepatitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2015;48:226-235.

20. Suzuki A, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Miquel R, Smyrk TC, Andrade RJ, et al. The use of liver biopsy evaluation in discrimination of idiopathic autoimmune hepatitis versus drug-induced liver injury. Hepatology 2011;54:931-939.

21. de Boer YS, van Nieuwkerk CM, Witte BI, Mulder CJ, Bouma G, Bloemena E. Assessment of the histopathological key features in autoimmune hepatitis. Histopathology 2015;66:351-362.

22. Kumari N, Kathuria R, Srivastav A, Krishnani N, Poddar U, Yachha SK. Significance of histopathological features in differentiating autoimmune liver disease from nonautoimmune chronic liver disease in children. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;25:333-337.

23. Tucker SM, Jonas MM, Perez-Atayde AR. Hyaline droplets in Kupffer cells: a novel diagnostic clue for autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:772-778.

24. Himoto T, Kadota K, Fujita K, Nomura T, Morishita A, Yoneyama H, et al. The pathological appearance of hyaline droplets in Kupffer cells is not specific to patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2017;10:8703-8708.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 1,766 View

- 143 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Sook-Hyang Jeong

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4916-7990Haeryoung Kim

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4205-9081 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print