Concurrent hepatic adenomatoid tumor and hepatic hemangioma: a case report

Article information

Abstract

A 45-year-old male with alleged asymptomatic hepatic hemangioma of 4 years duration had right upper-quadrant pain and was referred to a tertiary hospital. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans revealed a hypervascular mass of about 7 cm containing intratumoral multilobulated cysts. A preoperative liver biopsy was performed, but this failed to provide a definitive diagnosis. The patient underwent a partial hepatectomy of segments IV and VIII. The histologic findings revealed multifocal proliferation of flattened or cuboidal epithelioid cells and a highly vascular edematous stroma. Immunohistochemistry findings demonstrated that the epithelioid tumor cells were positive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), vimentin, calretinin, and cytokeratin 5/6, and were focally positive for CD10, and negative for WT1 and CD34, all of which support their mesothelial origin. Immunohistochemistry for a mesothelial marker should be performed for determining the presence of an adenomatoid tumor when benign epithelioid cells are seen.

INTRODUCTION

Adenomatoid tumors were first described by Golden and Ash1 and denoted the benign, often incidental, and typically well-circumscribed neoplasms of mesothelial origin.2 They occur mostly in the genital tract during a patient's reproductive age, although extragenital adenomatoid tumors have rarely been reported in various organs including the adrenal gland, heart, mediastinum, appendix, liver, pancreas, peritoneum, and pleura.3-5 We report a case of a large, hepatic adenomatoid tumor that was combined with a small cavernous hemangioma.

CASE REPORT

A 45-year-old Canadian man had been followed regularly at the local hospital because of a liver mass detected on abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scan four years previously. At the time of the first diagnosis, the liver had hypervascular features with a lobular and cystic portion seen on CT scanning, and which was regarded as a cavernous liver hemangioma. Three years later, he was transferred to our institute for further evaluation of his right upper quadrant pain. On the physical examination there was neither hepatomegaly nor a palpable abdominal mass. Routine laboratory tests including CBC, liver battery, and coagulation tests were within normal ranges. A serologic test was negative for both the hepatitis B virus surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody. Tumor markers such as α-fetoprotein, protein induced by vitamin K absence-II (PIVKA-II), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) were also within a normal range.

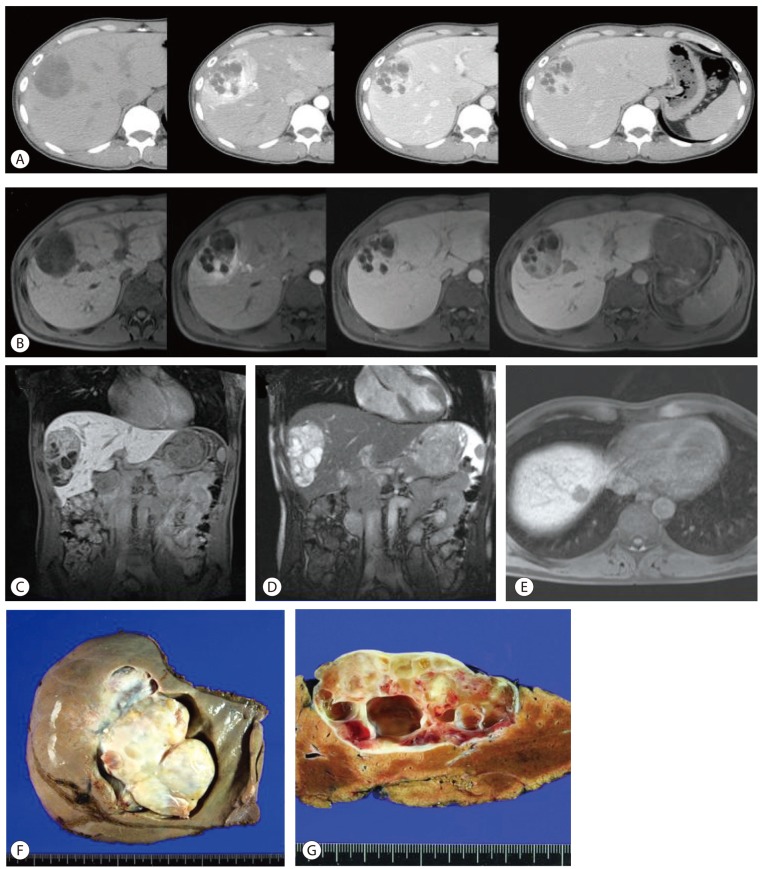

On liver dynamic CT, the mass in segments IV and VIII, and measuring 6.5×5.3 cm was hypervascular and showed intratumoral cystic change and calcification. There was another enhanced mass measuring 2.3 cm in the right hepatic dome and that was thought to be a hepatic hemangioma. The large hepatic mass was enhanced on arterial phase imaging of liver dynamic CT scan, but was not washed out in either early portal phase or delayed phase imaging (Fig. 1A). The liver mass was a well-defined, hypointense, solid mass on T1-weighted imaging and was hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging of MRI scan; there were multi-lobulated, cystic areas within the mass seen on MRI. Following enhancement with gadolinium-EOB-DTPA, the mass appeared hypervascular on the arterial phase and showed decreased enhancement on the delayed phase (Fig. 1B). Besides, there had been a renal cortical cyst which size was increased from 1.4 cm to 3.0 cm during 4 years of followup, but it was regarded as a simple benign cyst by imaging study.

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) images of a hepatic adenomatoid tumor, and gross findings of the resected tumor. (A) Dynamic CT images after contrast enhancement revealing enhancement at the arterial phase. However, no early washout pattern was observed in the portal or delayed phases. (B) Dynamic MR images after gadolinium-EOB-DTPA enhancement, showing hypervascularity in the arterial phase and decreased enhancement in the delayed phase. (C) Sagittal view of the tumor in an MR T1-weighted image, showing a low signal intensity comprising multiple cystic and solid portions. (D) Sagittal view of the tumor in an MR T2-weighted image, showing a high signal intensity comprising multiple cystic and solid portions. (E) A single concurrent hepatic hemangioma in the right hepatic dome, showing a low signal intensity in a T1-weighted MR image. (F) Grossly, a 7×6-cm-sized resected tumor that appears to be embedded in the liver parenchyma. The outer surface looks soft, grayish-white, and glistening. (G) Cross-sectional view of the resected tumor, showing multiple intratumoral cysts filled partly with fluid, partly with myxoid material, and with a hemorrhagic portion. The mass is well-encapsulated, pushing the normal liver parenchyma aside, with no evidence of infiltration of the surrounding tissue.

A preoperative liver core biopsy was performed, because a definitive diagnosis was not made. Since a malignancy could not be completely excluded and the patient had presented with right upper quadrant pain, partial hepatectomy of segments IV and VIII was performed. The patient made an uneventful recovery.

Pathology findings

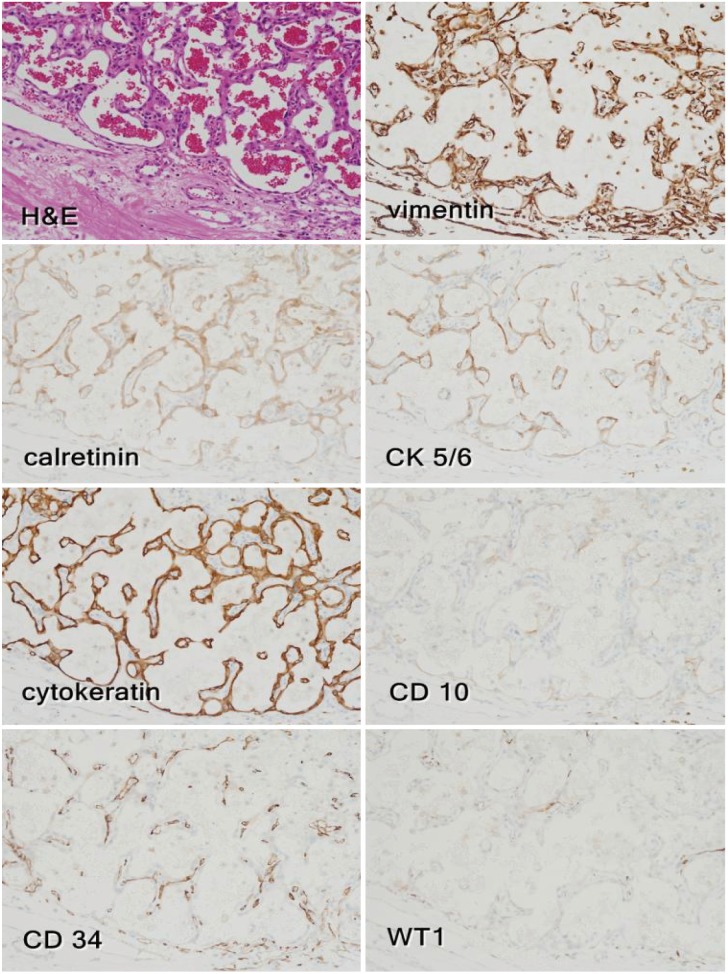

Preoperative liver biopsy showed multifocal proliferation of clear, cuboidal cells in a tubular and cystic structure and highly vascular edematous stroma. Because the clear cells were positive for cytokeratin and vimentin, metatstatic renal cell carcinoma was considered, although the tumor cells were negative for CD10 that is used as a marker for clear cell, renal cell carcinoma. The resected liver showed a solid mass measuring 7.5×6.5×3.7 cm and with a well-circumscribed border that was continuous with the Glisson's capsule and pushing the hepatic parenchyma. The mass was mostly solid, partly myxoid and hemorrhagic, and partly cystic with multiple, various sized cysts (Fig. 1F). The cut surface of the solid portion of the mass was mostly whitish-yellow, partly reddish, smooth, and glistening. The cysts were filled with serous fluid (Fig. 1G). Microscopically, the tumor showed proliferation of flattened or cuboidal epithelioid cells in tubular or glandular structures as well as highly vascular stroma with thin-walled blood vessels (Fig. 2). The epithelioid cells were diffusely positive for cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), vimentin, calretinin, and cytokeratin 5/6, were focally positive for CD10, and were negative for WT1 and CD34 (Fig. 3). These findings support the mesothelial differentiation of the tumor cells. Apart from this mass, there was an hepatic mass, measuring 2 cm in diameter and located in the right hepatic dome; the mass was a typical, cavernous hemangioma (Fig. 4).

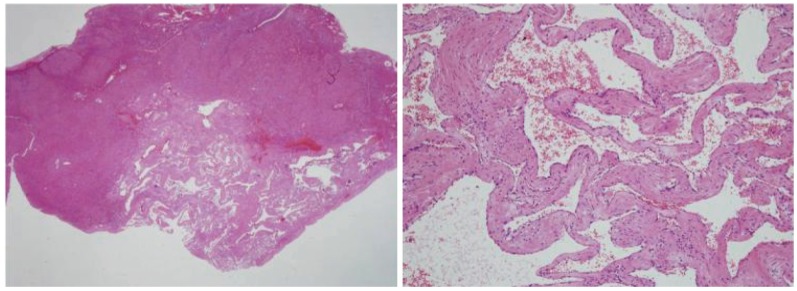

Microscopic findings of the resected hepatic adenomatoid tumor. (A) Low-power-field view of the resected tumor specimen, showing a well-encapsulated tumor mass without infiltration to the liver parenchyma (H&E, ×10). (B) Various-sized capillary anastomosis were observed (H&E, ×40).

Immunohistochemical staining of a hepatic adenomatoid tumor. The cystic or angiomatoid spaces are lined with flattened or cuboidal epithelioid cells containing numerous red blood cells (H&E, ×200). Immunohistochemistry revealed positivity for vimentin, calretinin, cytokeratin 5/6, and cytokeratin (AE1/AE3); the sections were also focally positive for CD10 and negative for WT1. Intervening CD34-positive, thin-walled blood vessels were also noted in the highly vascular portion.

DISCUSSION

Adenomatoid tumors of mesothelial derivation have been most often found in the male and female genital tracts, and are rarely reported in extragenital sites such as the adrenal gland, heart, mediastinum, appendix, intestinal mesentery, liver, pancreas, peritoneum, and pleura. Only two cases of hepatic adenomatoid tumor have been described in the medical literature, one of which was a solitary liver mass,6 and the other involving the liver and peritoneum.7 Here, we report the first case of a large sized hepatic adenomatoid tumor combined with a hepatic hemangioma.

In the preoperative liver core biopsy, two components were noted, i.e. CD34-positive thin blood vessels and cytokeratin positive cells. CD10 was focally positive at postoperative biopsy while it was negative at preoperative biopsy specimen that was insufficient for thorough pathologic examination. As the tumor cell was initially considered to be epithelial cells with CD10 immunopositivity, renal cell carcinoma was considered in the differential diagnosis, although the left renal cyst looked a simple benign cyst. Retrospectively, as mesothelial cells are also positive for various epithelial markers, specific markers of mesothelial cells, including calretinin and WT1, must have been examined in the liver biopsy specimen.

The preoperative differential diagnoses included sclerosing hemangioma, inflammatory pseudotumor, slow-growing well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma, and metastastic renal cell carcinoma due to the hypervascular feature of the tumors.

Radiologically, the findings of adenomatoid tumors range from a solid tumor to a cystic tumor depending on the content of the cystic spaces, smooth muscle, and fibrous tissue.8 As these tumors are difficult to differentiate from other benign or malignant tumors on clinical examination, ultrasonography, CT, and MR imaging, the situation usually leads to obtaining a both histopathologic and immunohistochemical diagnosis.

In general, the resected tumor in this patient was likely to be embedded in the liver parenchyma, abutted to the diaphragm, and pushing the normal structure oppressed but without infiltration or destruction.

Histologically, adenomatoid tumor is classified into four types; adenoid or tubular; angiomatoid or canalicular; solid or plexiform; and cystic.9 Thread-like bridging strands crossing the pseudotubular spaces are the characteristic morphologic features of adenomatoid tumor10 which is usually composed of gland-like spaces lined by single cubodial cells with prominent nuclei. As the tumor cells are extremely flat, the possibility of adenocarcinoma such as epithelial bile duct cancer seems unlikely. Also differential diagnoses of hepatic tumors composed of clear cell type include hepatocelluar carcinoma, metastatic clear cell carcinoma, and metastatic adrenal cortical carcinoma. And it is necessary to exclude vascular neoplasms such as hemangioma, epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and lymphangioma. Metastatic adenocarcinoma can be easily differentiated from adenomatoid tumor by its cytologic morphology such as an atypical and infiltrative border, the negativity for calretinin and CK5/6, and the positivity for carcinoembryonic antigen and MOC 31. And differentiation from clear cell type tumors and vascular neoplasms can be made possible by the use of immunohistochemical stainings for blood vessel endothelial markers (CD31, CD34, and factor VIII), lymphatic vessel markers (HBME-1), cytokeratin and vimentin.11 In the present case, the enlarged and proliferating capillaries in the edematous stroma were positive for CD34, while intervening epithelioid cells were negative for endothelial markers. Another differential diagnosis of adenomatoid tumor includes lipoma and metastatic carcinomas.12 As in the present case, metastatic clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma has the most difficult differential diagnosis because renal cell carcinoma only expresses both positive for cytokeratin and vimentin and has clear tumor cells with various cellular atypia.

In conclusion, preoperative core biopsy is important for obtaining a definite diagnosis in cases of large adenomatoid tumor arising in unusual sites in order to determine the optimal treatment because many adenomatoid tumors are small and incidentally identified. When the biopsy specimen reveals benign epithelioid cells, immunohistochemistry for mesothelial markers must be performed in addition to obtaining both epithelial and mesenchymal markers for an accurate differential diagnosis.

Notes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

AE-1

anion exchanger protein 1

AE-3

anion exchanger protein 3

CA 19-9

carbohydrate antigen 19-9

CD

cluster of differentiation

CEA

carcinoembryonic antigen

CK

cytokeratin

CT

computed tomography

EOB-DTPA

ethoxybenzyl diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid

HBME-1

anti-human mesothelial cell antibody

MOC-31

epithelial related antigen

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

PIVKA-II

protein induced by vitamin K absence-II

WT-1

Wilms' tumor-1 protein