Enhanced A-FABP expression in visceral fat: potential contributor to the progression of NASH

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

Adipose tissue is an active endocrine organ that secretes various metabolically important substances including adipokines, which represent a link between insulin resistance and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). The factors responsible for the progression from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis remain elusive, but adipokine imbalance may play a pivotal role. We evaluated the expressions of adipokines such as visfatin, adipocyte-fatty-acid-binding protein (A-FABP), and retinol-binding protein-4 (RBP-4) in serum and tissue. The aim was to discover whether these adipokines are potential predictors of NASH.

Methods

Polymerase chain reaction, quantification of mRNA, and Western blots encoding A-FABP, RBP-4, and visfatin were used to study tissue samples from the liver, and visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue. The tissue samples were from biopsy specimens obtained from patients with proven NASH who were undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to gallbladder polyps.

Results

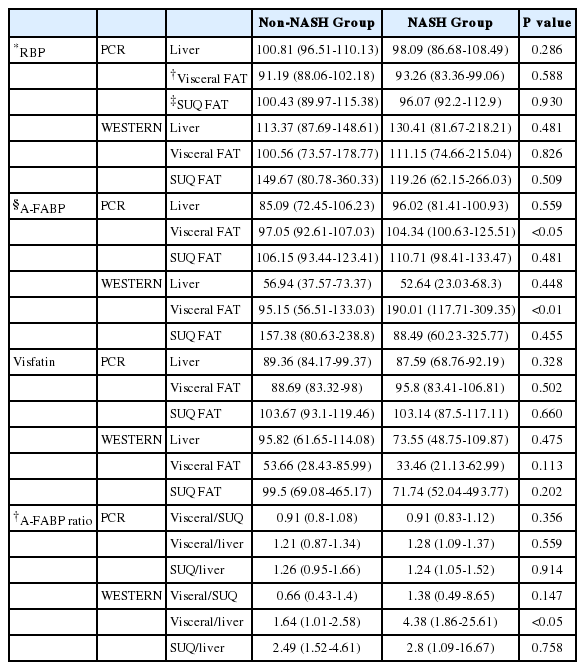

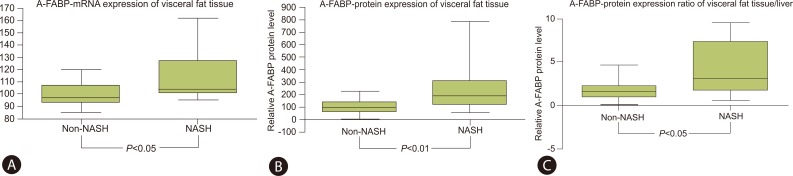

Patients were classified into two groups: NASH, n=10 and non-NASH, n=20 according to their nonalcoholic fatty liver disease Activity Score. Although serum A-FABP levels did not differ between the two groups, the expressions of A-FABP mRNA and protein in the visceral adipose tissue were significantly higher in NASH group than in non-NASH group (104.34 vs. 97.05, P<0.05, and 190.01 vs. 95.15, P<0.01, respectively). Furthermore, the A-FABP protein expression ratio between visceral adipose tissue and liver was higher in NASH group than in non-NASH group (4.38 vs. 1.64, P<0.05).

Conclusions

NASH patients had higher levels of A-FABP expression in their visceral fat compared to non-NASH patients. This differential A-FABP expression may predispose patients to the progressive form of NASH.

INTRODUCTION

Both insulin resistance and visceral fat play an important role in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Adipokines, a type of cytokine that is secreted by adipose cells, play multiple roles in the control of appetite and satiety, as well as fat metabolism. Adipokines also influence blood pressure, the inflammatory reaction, and the immune response. An imbalance in the production and secretion of adipokines can be secondary to chronic inflammation and obesity as well as the nutritional status of the patient. These changes can result in the development of NASH.1,2 NASH, which can progress into liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, has a poor prognosis so it is important to identify quickly this high-risk group.

Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing NASH. However, the invasiveness and possible adverse events of this procedure preclude its use as a screening tool for NASH.3 There is a great need to develop a non-invasive method to predict the degree of hepatic progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Since the adipokines are one of the predictive markers, many studies are searching to discover the relationship between adipokines and NASH. However, this association is not well established.

Therefore, this study evaluated the serum, the liver, and the adipose tissue for the expression of adipokines such as visfatin, A-FABP (Adipocyte fatty acid binding protein) and RBP-4 (Retinol binding protein-4). We also investigated whether these adipokines were potential contributor for the development of NASH.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

Between September 2008 and September 2009, the study population had a total of 30 Korean adult males who had gall bladder polyps over 1 cm. All subjects showed signs suspicious for NAFLD assessed by abdominal ultrasonography performed by the same radiology specialist and was defined as diffuse increased echogenicity of the hepatic parenchyma compared with the kidney, vascular blurring and deep-echo attenuation. These patients also had undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to gallbladder polyps. Parameters evaluated included anthropometric measures, blood chemistry, and liver ultrasonography. We excluded subjects if there was serology confirmed viral hepatitis, transferrin saturation >50%, daily alcohol ingestion ≥20 g, and the presence of other causes of liver disease. Also, patients were excluded if there was any metabolic or hereditary disease or cancer, chronic inflammatory disease, or the presence of infectious disease. Informed consent was obtained from all of the participating subjects and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kangbuk Samsung Medical Center.

Anthropometric data

Anthropometric data including height, body weight, and systolic and diastolic blood pressures (BP) were measured in duplicate and the results were averaged. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the weight in kilograms by the square of the height in meters (kg/m2).

Biochemical test

Blood samples were obtained after a 12-hour overnight fast. We determined fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglyceride (TG), fasting insulin, creatinine, and high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP). The following parameters of liver function were also obtained: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). The serum insulin concentration was measured using an immunoradiometric assay (INS-IRMA; Biosource, Nivelles, Belgium). As a marker of insulin resistance, the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated using the following formula: HOMA-IR = (fasting insulin {µIU/mL} × fasting glycemia {mmol/L})/22.5. The glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured using an immunoturbidimetric assay with a Cobra Integra 800 automatic analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland) with a reference value range of 4.4-6.4%. The A-FABP levels were measured by an ELISA kit (Uscn Life Science, Wuhan, China). The RBP-4 levels were measured by a Human RBP-4 ELISA kit (Millipore, St. Charles, Missouri, USA). The visfatin levels were measured by an ELISA kit (ALPCO, Salem, NH, USA).

Histopathology of liver and fat tissue

To control the liver biopsy size, the length of the biopsy was measured, and the number of portal areas on one cross-section was counted. The biopsy sample should contain representative tissue, be about 25 mm and/or contain 15 portal fields. Liver and visceral fat tissue was obtained using laparoscopic biopsy from liver and greater omentum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to gallbladder polyps. Subcutaneous abdominal fat was obtained using a 4 mm punch biopsy and was immediately frozen for future analysis. After collecting tissues from patients, wash with cold-PBS. All biopsied tissues put in 15 mL sterile tube moved to the lab in liquid nitrogen and keep at -80℃ deep freezer. It was stained with hematoxylin-eosin, reticulin, and Gomori trichrome stains. All histologic slides were analyzed by the hepatopathologist (SW Chae) according to the NAFLD Activity Score (NAS). The score is defined as the sum of the scores for steatosis (0-3), lobular inflammation (0-3), and ballooning (0-2); thus ranging from 0 to 8. We classified our patients in two groups: the NASH group (NAS score ≥5) and the non-NASH group (NAS score ≤4).4

RNA isolation and reverse transcription, polymerase chain reaction (PCR)

Three to five-gram samples of subcutaneous and visceral fat were obtained during the laparoscopic procedure. Hepatic tissue was also obtained at random from two sites during the procedure. The total RNA was isolated from the extracted tissues using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, USA). A 1.5 microgram sample of RNA was reverse transcripted using Takara RNA PCR Kit (Takara Biomedicals, Japan). Subsequent amplifications were using 1 µL of cDNA, Hotstar Taq polymerase (QIAGEN) and specific primer as follows:

-

A-FABP

(sense) 5'-GAAACTTGTCTCCAGTGAAAAC-3'

(antisense) 5'-GCTTGGGAGAAAATTAGTTGCT-3'

-

RBP-4

(sense) 5'-GCCTCTTTCTGCAGGACAAC-3'

(antisense) 5'-CGGGAAAACACGAAGGAGTA-3'

-

Visfatin

(sense) 5'-G GGAAAGACCATGAAAAAGA-3'

(antisense) 5'-AAGGCCATTAGTTACAACAT-3'

-

β-actin

(sense) 5'-CAAGAGATGGCCACGGCTGCT-3'

(antisense) 5'-TCCTTCTGCATCCTGTCGGCA-3'.

The PCR mixtures were subjected to 35 cycles of amplifications by denaturation (30 sec at 95°), annealing (1 min at 60° for A-FABP, RBP-4, 52° for visfatin and 68° for β-actin) and extension (1 min at 72°). PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Protein extraction and Western blot analysis

The samples were lysed using a PRO-PREP PROTEIN extraction solution (Intron, Korea). Extracts were separated by 10-20% Tris-Glysin gel (Invitrogen, USA) followed by electrotransfer to PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA). The extracts were probed with polyclonal or monoclonal antisera, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit, anti-mouse IgG, respectively. The products were visualized by chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer's instructions (Ab frontier, Korea). Specific antibodies were obtained from the following companies: RBP-4 from Abcam, A-FABP from Abnova, visfatin from Novus Biologicals, and actin from Abcam.

Statistical analysis

All results were presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD) or median (inter-quartile range or Min-Max range). Continuous variables were compared, using the Student's t test for normally distributed variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. The strength of association between continuous variables was reported using Spearman rank correlation. The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Clinical features of the study subjects

The study subjects (n=30) were classified into the NASH group (n=10) and the non-NASH group (n=20) using NAS system. The average age of each group was 42.5 years (range 37.8-52.8 years) in the NASH group and 52.5 years (range 38.3-65.0 years) in the non-NASH group.

The levels of serum HbA1c, insulin, and fasting blood glucose were 6.3%, 14.07 µIU/mL and 108.0 mg/dL in the NASH group. However, these same parameters were 5.9%, 10.45 uIU/mL and 98.0 mg/dL in the non-NASH group. These findings show significantly higher levels in the NASH group (P=0.012, P=0.026, and P=0.034 respectively).

No significant differences were shown in the levels of BMI, HOMA-IR, HDL cholesterol, serum triglyceride, liver function tests, and serum ferritin (Table 1).

Serum adipokines in the NASH group and the non-NASH group

Serum RBP-4 and visfatin showed no significant differences between the NASH and the non-NASH group (P=0.412, and P=0.451, respectively). The A-FABP showed a tendency towards a higher level in the NASH group (6.75, 1.04-21.86) than the non-NASH group (2.95, 1.46-6.18), but it was not statistically significant (P=0.714) (Table 2).

The expression of adipokine mRNA in visceral and subcutaneous fat in the NASH and the non-NASH group

The visfatin levels in the visceral and the subcutaneous fat, measured by PCR in each tissue, were higher in the NASH group than the non-NASH group. The RBP-4 levels were lower in the NASH group than in the non-NASH group, but no significant difference were found. However, the expression of A-FABP in the visceral fat was higher in the NASH group (104.34, 100.63-125.51) than the non-NASH group (97.05, 92.61-107.03) and this difference was statistically significant (P<0.05) (Table 3, Fig. 1A).

The expression of adipokine protein in the NASH and the non-NASH group

The Western blot analysis of the visceral and the subcutaneous fat tissue showed a lower expression of visfatin in the NASH group than the non-NASH group. The protein expression of RBP-4 in the visceral fat tissue was higher in the NASH than the non-NASH group. However, those levels in the subcutaneous fat tissue showed a lower figure in the NASH than the non-NASH group. Both the visfatin and RBP-4 showed no statistically significant difference.

The expression of the A-FABP protein in the visceral fat showed a higher figure in the NASH group (190.01, 117.71-309.35) than the non-NASH group (95.15, 56.51-133.03) and this difference was statistically significant (P<0.01) (Table 3, Fig. 1B).

The expression ratios of adipokines among liver, visceral, and subcutaneous fat in the NASH group and the non-NASH group

The expression ratio of A-FABP for visceral fat to liver measured by Western blot was higher in the NASH group (4.38, 1.86-25.61) than the non-NASH group (1.64, 1.01-2.58) with statistical significance (P<0.05) (Table 3, Fig. 1C).

DISCUSSION

Visceral fat, a potent predictor for NAFLD, shows a positive and quantitative association with hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. This visceral fat is independently associated not only with severe NASH, but also with hepatic fibrosis, and insulin resistance.5 Although the exact mechanism of how the visceral fat adversely affects the liver has not yet been established, the "portal/fatty acid flux theory" proposes that visceral fat, via its unique location and increased lipolytic activity, can lead to increased secretion of toxic free fatty acids. Those fatty acids are then delivered in high concentrations to the liver via the hepatic portal vein. The high concentration delivery of those fatty acids not only increases the storage and accumulation of visceral fat, but also causes hepatic insulin resistance.6,7

Concerning the pathogenesis of NASH, there are several explanations. One hypothesis states that insulin resistance contributed to the increased secretion of fatty acids from adipose tissue thereby increasing the influx of fatty acids to the liver. The 'two-hit hypothesis' explains that the hyper-oxidation of the lipids and the oxidative stress increases the activation of the astrocyte and the level of TGF-β and it facilitate hepatic fibrosis.8-10 Another hypothesis states that the high concentration of free fatty acids directly damages the liver.11 The variety of adipokines secreted from adipocytes, together with free fatty acids, play an important role in the development of NASH.12

Visfatin is an adipokine secreted from visceral fat. it facilitates the synthesis of triglyceride and plays an insulin-like action by acting on the insulin receptor. This later action is associated with insulin resistance, inflammatory reaction, and metabolic syndrome.13-15 In recent articles the level of serum visfatin in the NASH group was lower than that of a simple fatty liver.16,17 In our study, the levels of the protein expression of visfatin in the liver, the visceral, and the subcutaneous fat were lower in the NASH group, although they did not reach statistical significance.

The RBP-4, a type of adipokine mainly produced by adipocytes and hepatocytes, acts on the insulin signal pathway and is known to increase the insulin resistance.18 Since the serum RBP-4 is more highly expressed in the visceral fat than the subcutaneous fat tissue, it is known as an index of the amount of fat in abdomen.19 Some studies reported a negative association between the degree of progression of hepatic disease and the serum level of RBP-4.20,21 In our study, we observed that the expressions of RBP-4 mRNA in the liver and the fat tissue were lower in the NASH than in the non NASH, but they were not statistically significant.

The A-FABP, which is expressed in adipocytes and macrophages, is a kind of lipid-binding protein with a size around 15 kD. This lipid binding protein not only increases the intracellular transport of free fatty acids, but it is also being proposed as a predictive biomarker for metabolic disease such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and metabolic syndrome.22 Although its mechanism is not clearly known, some animal studies reported that A-FABP's interaction with adipocytes and macrophages plays a particular role in inflammation and insulin resistance. A rat lacking in A-FABP and epidermal-FABP showed decreased levels in fatty liver, atherosclerosis, and dyslipidemia.23,24 In a clinical study, it was shown that the serum level of A-FABP had a positive association with metabolic syndrome, HOMA-IR, TNF-α, and the risk of NAFLD.25 A recent study showed not only that the serum level of A-FABP had been higher in patients with fatty liver disease than normal subjects, but also that it had significantly increased in the NASH patients compared to subjects with simple steatosis. Also the high A-FABP serum level had an association with hepatic inflammation, and the degree of fibrosis.26 Our study demonstrated a higher serum level of A-FABP in the NASH group compared with the non NASH group, but it was not statistically significant.

In our study, we measured the serum A-FABP level, the expression of A-FABP mRNA, and the protein in tissue (liver, visceral, and subcutaneous fat). The NASH group, compared to the non-NASH, showed significantly higher levels in the expression of both A-FABP mRNA and protein in visceral fat. These findings suggest that the A-FABP expression in visceral fat, rather than visfatin or RBP-4, was more likely a potential contributor for the progression of NASH. The degree of expression of A-FABP mRNA and protein in visceral fat was a more important contributor in NASH than in other tissue. The higher visceral fat/liver ratio for A-FABP protein expression in the NASH group shows that the relatively high degree of A-FABP expression in visceral fat has an important impact on the development of NASH.

One of limitations of this study is the small sample size and all the subjects are male. Although all the subjects were classified into two groups based on the NAS system, the small number of patients could be a source of error. Another limitation is the study design. In this cross-sectional study design, the causal relationship between the expression of visceral A-FABP and the development of NASH could not be clarified. Also this study did not suggest any adipokine as a noninvasive marker and any conclusive role of adipokine in diagnosis NASH patients, but this data demonstrated the potential role of A-FABP in pathogeniesis and diagnosis in progressive NAFLD patients and further prospective studies with more cases should be warrented.

Despite these limitations, the strengths of this study include the fact that the tissues were taken from liver, visceral fat, and subcutaneous fat distinctively, the comparisons were made for the degree of expression of mRNA and protein, and a liver biopsy was performed to know the actual degree of NASH with NAS criteria.

In conclusion, the high expression of A-FABP mRNA and protein in visceral fat, and the ratio of visceral/liver for A-FABP protein expression were contributor for NASH. Further studies on the pathophysiological relationship between adipokines and NASH are necessary to identify a non-invasive biomarker to replace liver biopsy for the diagnosis and follow-up of NASH.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the research fund of the Korean Association for the Study of the Liver (KASL).

Notes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Abbreviations

A-FABP

adipocyte-fatty acid binding protein

NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

PCR

polymerase chain reaction

RBP-4

retinol binding protein-4