INTRODUCTION

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) is a rare subtype of extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. IVLBCL is characterized by the presence of lymphoma cells only in the lumina of small vessels, particularly capillaries.1 Clinical presentation is extremely heterogeneous, ranging from monosymptomatic forms such as fever, pain or local symptoms, to rapidly progressing multiorgan failure. The atypical characteristics of IVLBCL, including the absence of marked lymphadenopathy and aggressive clinical behavior, tend to result in the delay of timely and accurate diagnosis. Thus, the prognosis of IVLBCL is extremely poor.2 Median survival ranges from a few months without treatment to several years with rituximab-containing polychemotherapy.3

Microscopic findings of primary and secondary hepatic lymphomas (non-Hodgkin or Hodgkin lymphoma) include infiltration of lymphoid tissue that is composed of small lymphocytes with oval and irregular nuclei and clear cytoplasm in the liver parenchyma.4 In cases of Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphomas, the CT appearance of hepatic involvement can be divided into three categories: solitary hepatic mass lesions ranging from less than 1 cm to approximately 10 cm, multifocal hepatic lesions similar in appearance to metastatic disease or multifocal hepatoma, and diffuse hepatic involvement with lesions that often have the same attenuation as hepatic parenchyma.5 On MRI, lymphomatous lesions usually have low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and variable signal intensity on T2-weighted images. The lesions usually show mild enhancement after gadolinium chelate administration.6

The literature contains little about state-of-the art imaging findings for IVLBCL. We present a case of hepatic involvement of IVLBCL with CT and MRI findings that might be helpful for IVLBCL diagnosis. We describe an IVLBCL patient who presented with dyspnea, fever and elevated liver enzyme levels.

CASE REPORT

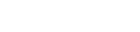

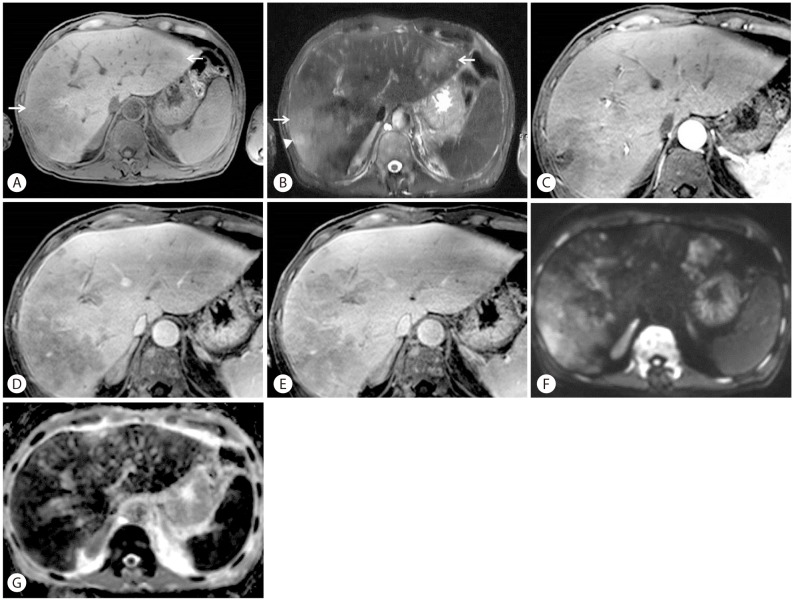

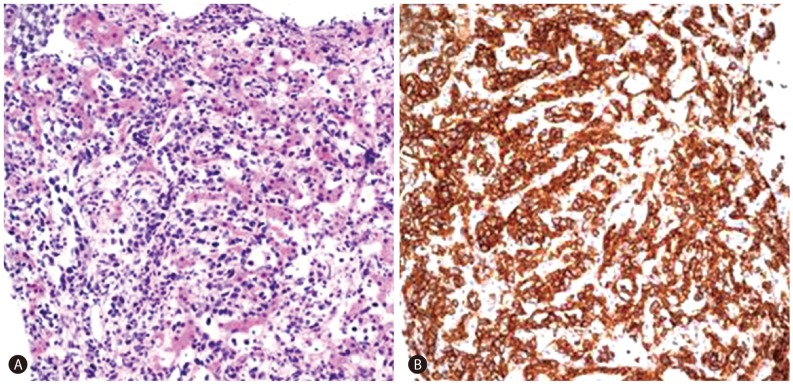

A 58-year-old man who was previously healthy presented with six-week history of dyspnea and a one-day history of fever. Body temperature at presentation was 38.8Ōäā. Laboratory studies revealed a white blood cell count of 10.2 ├Ś 103/┬ĄL with hemoglobin 8.5 g/dL. Total bilirubin level was 2.6 mg/dL (normal range, 0.2-1.5 mg/dL). Liver enzyme levels were elevated with an alanine aminotransferase 72 U/L (normal range, 0-40 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase 151 U/L (normal range, 0-40 U/L), and alkaline phosphatase 155 U/L (normal range, 53-128 U/L). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 6151 IU/L (normal range, 240-480 IU/L). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 12 mm/hr (normal range, 0-22 mm/hr). To evaluate the cause of dyspnea, chest CT was performed and there was no demonstrable abnormality to explain the symptom. On laboratory findings patient showed anemia which was suspected as the cause of dyspnea. The patient was known to have a hemangioma in liver segment VII that had been incidentally found in 2004 and had grown from 1.4 cm to 3.0 cm on follow-up ultrasonography. Therefore, imaging studies were performed to further evaluate the hepatic hemangioma and investigate the cause of the elevated liver enzymes. Contrast-enhanced dynamic CT of the liver showed multiple ill-defined non-enhancing areas in the hepatic lobes. Lesions appeared as low-attenuating areas of geographic pattern compared with normal-appearing parenchyma during all three phases. Hepatic vascular structures traversed normally through lesions without mass effects (Fig. 1). Gadoxetic acid-enhanced liver MRI (Fig. 2) revealed multiple mass-like lesions with ill-defined margins and homogeneous hypointensity on pre-contrast T1-weighted images and homogeneous hyperintensity on pre-contrast T2-weighted images. The lesions showed little contrast enhancement during dynamic scans and diffusion restriction on diffusion-weighted images. Hepatic vascular structures within the lesions were normal without mass effects, similar to the CT images. Ultrasonography-guided percutaneous biopsy was performed under the impression of a suspected unusual malignant tumor. Microscopic analysis showed abundant tumor cells filling the hepatic sinusoids and tumor cells positive for CD20 (Fig. 3). The patient was found to have no abnormality in central nerve system, skin, and other parts of the abdomen on physical examination and imaging studies. Bone marrow biopsy was performed and the final pathologic diagnosis was IVLBCL. Immediately after diagnosis, chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone and monoclonal antibody rituximab (R-CHOP) was initiated, and after a few days, fever began to subside. Follow-up CT (Fig. 4) 3 months later showed nearly total resolution of the liver lesions. The patient was alive at 17 months with no sign of disease progression.

DISCUSSION

Despite its recognition as a distinct disease, no large studies of IVLBCL have been reported.7 Skin and the central nervous system are the most commonly involved sites and IVLBCL of the liver is very rare. To our knowledge, this is the first report of imaging findings of hepatic involvement of IVLBCL.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the WHO classification, is a very rare non-Hodgkin's lymphoma that is estimated to be <1% of all lymphomas. IVLBCL is characterized by nearly exclusive intravascular neoplastic proliferation of B lymphocytes, usually without involvement of lymphoid tissues and peripheral blood.8 IVLBCL has been described in patients from 34-90 years of age, with a median age of 70 years. It occurs equally in women and men and usually shows rapid progression and short survival, with only transient remission.1

IVLBCL can involve any organ and is usually widely disseminated at the time of diagnosis. Because of its distribution, IVLBCL can present with a wide range of signs and symptoms that are generalized and nonspecific (e.g., B symptoms, cytopenias), or localized and related to the involved organ (e.g., cutaneous lesions, neurologic deficits, hepatic or renal insufficiency). These findings result in a variety of possible differential diagnoses including autoimmune, infectious, and neoplastic. Due to the lack of lymph node involvement or formation of mass lesions, the clinical picture is further complicated and the ability to make a prompt diagnosis is undermined.9

Laboratory findings are not specific but indicative for suspected IVLBCL. Increased serum LDH and ╬▓2-microglobulin levels are observed in more than 80% to 90% of IVLBCL patients. An elevated ESR is present in 43%. Altered hepatic, renal, or thyroid function tests are observed in 15% to 20%. These functional tests should be always included in staging work-up for IVLBCL.10

The predominant microscopic finding of IVLBCL is atypical blastoid cells with multiple mitoses that exclusively proliferate within vascular and sinusoidal structures of lymph nodes, liver, lung or bone marrow. Immunhistochemical staining is positive for the Bcell markers CD20 and CD79a in the absence of staining for T-cell markers. Occasionally, CD5 can be expressed as well.8

Radiologic findings in the case presented here revealed low attenuating infiltrative mass lesions with no enhancement on dynamic CT images. Vascular structures were noted within the mass with no mass effects. On MRI, the lesion showed homogeneous hypointensity on T1-weighted images, homogeneous hyperintensity on T2-weighted images and diffusion restriction.

Both primary and secondary hepatic lymphomas (non-Hodgkin lymphoma or Hodgkin disease) tend to show mild enhancement after contrast administration including homogeneous and rim-like pattern. Central necrosis may occur and produce a heterogeneous appearance. In addition, associated lymphadenopathy is noted in most patients with primary or secondary hepatic lymphomas.11 The patient in our case had multiple, ill-defined nonenhancing areas in the hepatic lobes that had a homogeneous appearance. Central necrosis and lymphadenopathy were absent. These findings could aid in the differential diagnosis of IVBCL from other forms of primary and secondary hepatic lymphomas.

Other liver diseases of diffuse pattern including malignant or non-malignant infiltrative diseases can be considered as differential diagnosis. The most common malignant lesion is hepatic metastasis of diffuse infiltrative pattern that can be differentiated from IVBCL on the bases of clinical context and imaging findings. Diffuse non-malignant infiltrative diseases include hemochromatosis and amyloidosis. Hemochromatosis typically shows diffuse high attenuation at CT and hypointensity at T2 weighted MRI whereas IVBCL shows low attenuation on CT and hyperintensity on T2 weighted image. Hepatic amyloidosis usually presents as hepatomegaly and multiorgan involvement is common unlike IVBCL.

No randomized, controlled trials have compared treatments of IVBCL. In most cases, IVBCL is disseminated at the time of diagnosis, warranting treatment with systemic therapy. An anthracycline-based chemotherapy regimen such as R-CHOP is recommended in cases with a B-cell immunophenotype.1

We presented a rare case of IVBCL of the liver without known radiologic features. IVBCL shows a wide range of signs and symptoms with no specific laboratory findings. However, when a patient presents with fever of unknown origin and elevated liver enzymes with infiltrative mass lesions with no enhancement on liver CT or MRI, as in our case, IVBCL involvement of the liver should be considered for prompt diagnosis and treatment.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print