| Clin Mol Hepatol > Volume 27(1); 2021 > Article |

|

See the commentary-article "Old hepatitis B virus never dies: It just hides itself within the host genome" on page 107.

ABSTRACT

Background/Aims

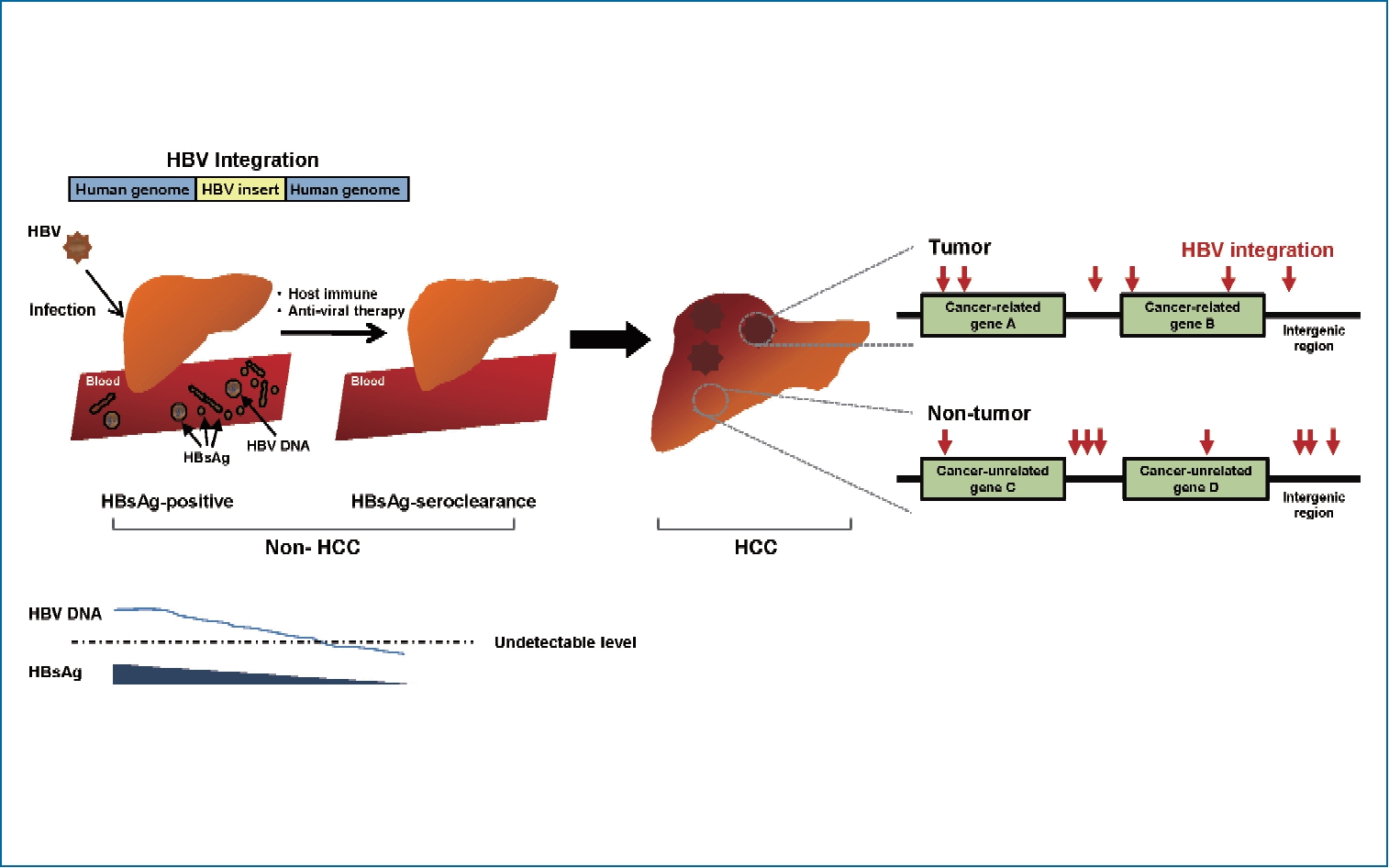

The role of hepatitis B virus (HBV) integration into the host genome in hepatocarcinogenesis following hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance remains unknown. Our study aimed to investigate and characterize HBV integration events in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients who developed hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after HBsAg seroclearance.

Methods

Using probe-based HBV capturing followed by next-generation sequencing technology, HBV integration was examined in 10 samples (seven tumors and three non-tumor tissues) from seven chronic carriers who developed HCC after HBsAg loss. Genomic locations and patterns of HBV integration were investigated.

Results

HBV integration was observed in six patients (85.7%) and eight (80.0%) of 10 tested samples. HBV integration breakpoints were detected in all of the non-tumor (3/3, 100%) and five of the seven (71.4%) tumor samples, with an average number of breakpoints of 4.00 and 2.43, respectively. Despite the lower total number of tumoral integration breakpoints, HBV integration sites in the tumors were more enriched within the genic area. In contrast, non-tumor tissues more often showed intergenic integration. Regarding functions of the affected genes, tumoral genes with HBV integration were mostly associated with carcinogenesis. At enrollment, patients who did not remain under regular HCC surveillance after HBsAg seroclearance had a large HCC, while those on regular surveillance had a small HCC.

Conclusions

The biological functions of HBV integration are almost comparable between HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-serocleared HCCs, with continuing pro-oncogenic effects of HBV integration. Thus, ongoing HCC surveillance and clinical management should continue even after HBsAg seroclearance in patients with CHB.

Graphical Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary cancer of the liver and the fifth most common cancer globally [1]. One of the major etiologic causes of HCC development is chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), especially in Asia and Africa. HBV-induced hepatocarcinogenesis is a complex and multifactorial process. This virus can produce onco-proteins such as HBV X protein (HBx), HBV large surface protein (L-HBs), or middle-sized HBV surface protein (MHBst) and drive the integration of HBV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequences into the human genome. These are involved in hepatocarcinogenesis as a direct oncogenic potential. Additionally, host immune-mediated cytolysis against HBV during long-lasting host-virus interaction ultimately results in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, which can indirectly cause HCC.

HBV genomic integrations have been reported in over 80ŌĆō90% of HBV-associated HCCs. HCC cells may contain single or multiple discrete HBV integrants within the human genome, which generate various genetic alterations, including deletions, translocations, fusion transcripts, and global genomic instability [2,3]. These alterations result in the selection of non-cancerous hepatocyte clones with survival advantages. Within this context, neoplastic clones with deregulated cell proliferation and suppressed apoptosis can ultimately arise and expand, resulting in overt HCCs [2,3].

Studies have shown HBV integration events even in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-negative HCC patients with anti-HCV antibody, and alcohol-related or cryptogenic liver disease, indicating its potential to induce liver cancer, especially in patients with occult HBV infection (OBI) [4,5]. Though rare, some chronic HBV carriers experience HBsAg seroclearance during the course of chronic hepatitis B (CHB), with a rate of approximately 1% per year [6]. Animal studies revealed that integrated forms of HBV still persist after HBsAg clearance [7,8]. It is unknown whether these persistent integrated HBV forms in the liver contribute to HCC risk. The clinical observations of an association between OBI and an increased risk of progressive liver disease or HCC suggest that the intrahepatic persistence of integrated forms of HBV may act as targets for low-level ongoing antiviral immune attacks, leading to disease progression [8,9]. Unfortunately, there is a lack of clinical evidence to characterize viral integrants and evaluate their role in HCC development following HBsAg seroclearance in chronic HBV carriers.

Advances in massive parallel sequencing technology have helped to overcome the technical limitations on earlier research methods for HBV integration, such as Southern blots or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods, and enabled highly efficient genome-wide detection of HBV integration. In this study, we performed a next generation sequencing (NGS)-based, high-throughput capture assay for HBV integration utilizing Korean genotype-specific probes. The aim of our study was to investigate the frequency and patterns of HBV integration, as well as characterize integration events in CHB patients developing HCC after HBsAg seroclearance.

Between December 2011 and December 2018, chronic HBV carriers with newly-diagnosed HCC at the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, South Korea, were screened for inclusion in the study. Among them, seven patients who developed HCC after HBsAg loss and had available stored liver tissue were included in the analysis. The diagnosis of HCC was made based on typical imaging analyses, consistent with the criteria of Korean National Cancer Center guideline [1] and finally confirmed pathologically. The liver tissue samples were unaffected by hemangioma or other benign tumor lesions and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at ŌĆō80┬░C. The diagnosis of liver cirrhosis was made by pathological examination or clinical evidence of cirrhosis, including nodularity or splenomegaly on liver imaging and/or thrombocytopenia [10]. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Catholic University of Korea (KC16TISI0436), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Intrahepatic HBV integration in liver tissues was identified by NGS-based high-throughput targeted sequencing, which was modified based on HBV probe-based capture technology [11]. The HBV hybridization probes were designed to tile, based on eight Korean full HBV genome sequences (GenBank Accession numbers AY641559.1, DQ683578.1, GQ872211.1, GQ872210.1, JN315779.1, KR184660.1, AB014381.1, AB014395.1, and D23680.1 Hepatitis B virus complete genome sequence; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore). The probes were prepared to capture the HBV inserted fragments in the host genome and these fragments were further sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. The number of total probes was 215, and the probe group size was 25.595 kbp. With these designed probes, 100% sequence coverage was achieved for all given HBV sequences. The workflow for detecting HBV integration is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

The HBV probe capture assay using the Illumina NGS workflow was conducted as follows. Briefly, 1 ug of input genomic DNA was fragmented to 150ŌĆō200 bp by adaptive focused acoustic technology (AFA; Covaris, Woburn, MA, USA). The fragmented DNA was repaired; an ŌĆśAŌĆÖ was ligated to the 3ŌĆÖ end and then Agilent adaptors ligated to the fragments. After a ligation assessment, the adaptor-ligated products were PCR-amplified. For HBV viral capture, 250 ng of DNA library was used according to the standard Agilent SureSelect Target Enrichment protocol. Hybridization to the capture baits was performed at 65┬░C using the heated PCR cycler lid option at 105┬░C for 24 hours. After amplification of the captured DNA, the final purified product was quantified according to the manufacturerŌĆÖs instructions (qPCR quantification protocol guide) and qualified using the TapeStation DNA Screen Tape D1000 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Finally, paired-end 100-bp read-length sequencing of the purified captured DNAs was carried out by Illumina HiSeq 2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturerŌĆÖs instructions.

We generated a modified reference by merging the human (UCSC assembly hg19, original GRCh37 from National Center for Biotechnology Information, February 2009) and HBV (DQ683578.1) genome. Then the paired-end reads were mapped to the reference by BWA-MEM (bwa-0.7.12). Duplicates were removed by Picard (Picard-tools-1.130). The final bam file was sorted according to chromosomal coordinates. After mapping the paired-end sequences to the human reference and HBV reference, the chimeric reads were extracted using an in-house script, and breakpoints were predicted from the chimeric reads that aligned both to the human and virus genome. The HBV sequences of chimeric reads that matched the virus genome reference by 30 bp or longer were considered to be integrated HBV sequences. To minimize errors in the experimental procedure and remove the noise signals, we utilized the mapping quality (MQ) and read counts of the host-virus chimeric DNA fragments for HBV integration breakpoint calling. For quality of phred score, MQ cut-off values of 10, 20, 30, and 40 indicates 10%, 1.0%, 0.1%, and 0.01% probabilities of incorrect base calls, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). HBV breakpoints with chimeric read counts of Ōēź2 and an average MQ of Ōēź20 were defined as true signals.

PCR and Sanger sequencing were done to validate the integrated HBV sequences in selected HBV-human junction breakpoints at the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and mixed-lineage leukemia 4 (MLL4) genes. Sequencing primers were designed based on the paired-end reads, with one primer located in the human genome and the other in the HBV genome. The PCR conditions with the primer sequences for a representative case are shown in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Data were expressed as median (range) or mean┬▒standard deviation. The proportions and number of HBV integration breakpoints were represented in the bar or pie charts. Statistical analyses were carried out to compare the values between two groups. StudentŌĆÖs t or Mann-Whitney U tests were used for continuous variables, and the chi-square test or FisherŌĆÖs exact test was used for categorical variables. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 21.0 (SPSS, Inc.. IBM Company, Chicago, IL, USA).

The enrolled seven HCC patients were all males aged 58.4┬▒10.4 years. Two patients achieved HBsAg seroclearance during antiviral therapy, while the remaining five did so spontaneously without antiviral therapy. Five (71.4%) of the seven patients had detectable HBV DNA in their serum at the time of HBsAg seroclearance or during the follow-up period after seroclearance, with serum HBV DNA levels ranging between <10 and 695 IU/mL. Paired tumor and adjacent non-tumor tissues were available in three patients, while only tumor tissue was available for the remaining four. Thus, our study examined 10 samples (seven tumors and three non-tumors) from the seven HCC patients. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1.

Using HBV probe capture technology (Supplementary Fig. 1), we obtained an average 61,214,931 raw reads from the specimens. After removing reads that were completely mapped against the HBV genome (DQ683578.1), a total of 1,811 reads that were partially mapped against the human genome reference (HG19) were extracted. We finally obtained 1,554 effective reads comprising potential integration events. HBV capture sequencing data were 6.12 Gb on average. Overall, six patients (85.7%) with HBsAg seroclearance had genomic integration of HBV DNA; eight (80.0%) of 10 samples tested positive for HBV integration. In our survey, we detected a total of 29 HBV integration breakpoints, with a mean of 2.90 integration breakpoints per sample (range, 0-8/sample) (Table 2). To confirm the HBV integrations, we randomly selected 18 breakpoints at the affected genes for PCR analysis in the present and other independent samples and successfully validated 88.9% of the integration sites (Supplementary Table 4).

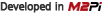

The HBV integration frequency was compared between the tumors and non-tumors. The number of integrated HBV DNA breakpoints was higher in the non-tumor tissues than in the tumor tissues. Breakpoints were detected in all of the non-tumor (3/3, 100%) and five of the seven (71.4%) tumor samples (Fig. 1A). The average number of HBV integration breakpoints was 2.43 per tumor sample and 4.00 per non-tumor sample (Fig. 1B).

We next evaluated HBV integration according to the HBV viremia status. HBV integration breakpoints were more frequent in patients with detectable viremia than in those without. In patients with detectable serum HBV DNA, integrated HBV DNA breakpoints were detected in 83.3% (5/6) of the samples. The average frequency of HBV integration was non-significantly higher in patients with detectable HBV DNA than in those with undetectable HBV DNA (3.33 vs. 2.25 per sample, respectively; P=0.513) (Fig. 1C).

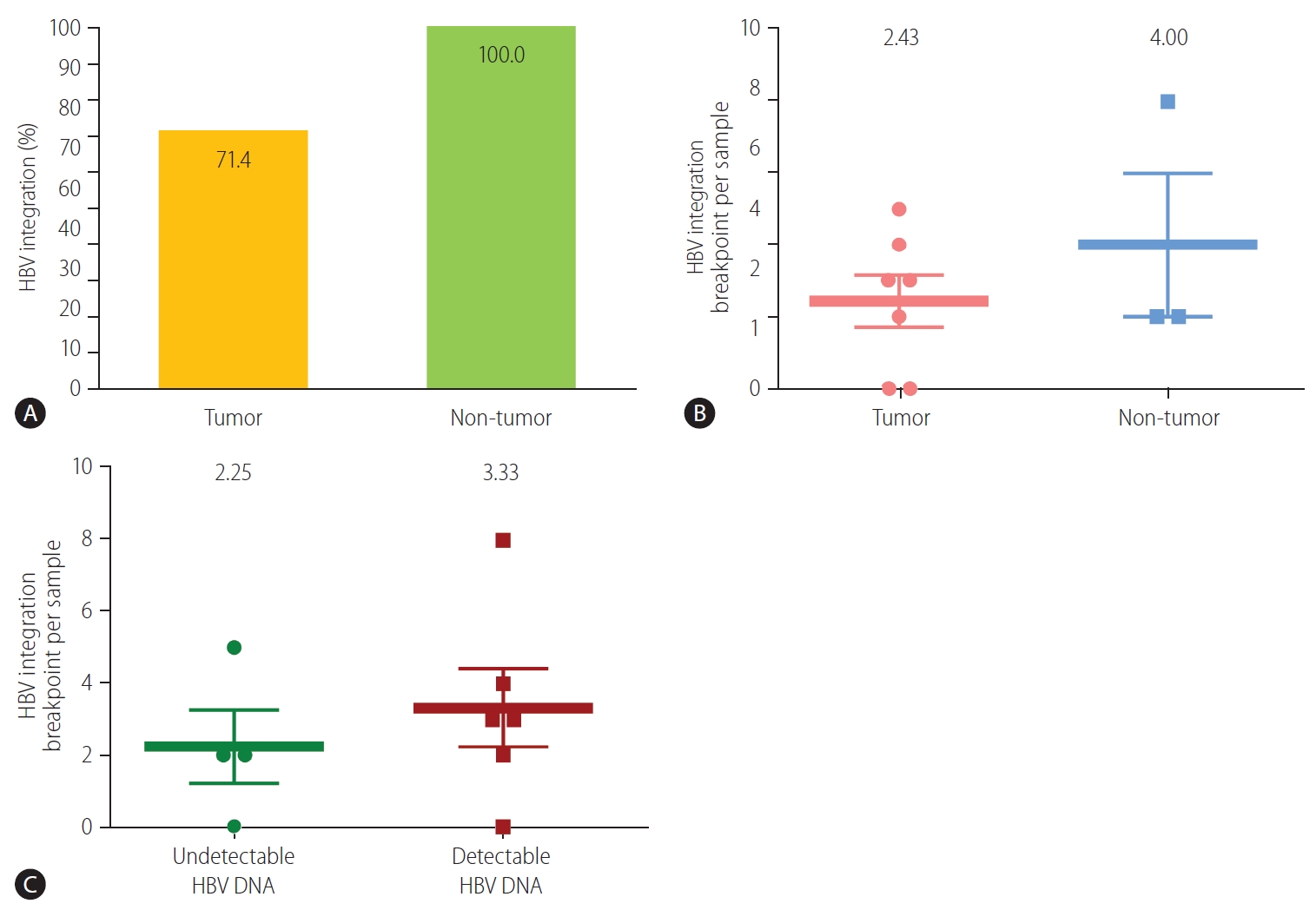

HBV integration breakpoints were distributed across the entire human genome, but most preferentially noted in chromosome 5 (6/29, 20.7%), especially in tumors (Fig. 2A, Table 2). The distribution of HBV integration was differentially observed in the tumor and non-tumor tissues. For tumors, the integration sites were more enriched within the genic area (58.8%, intragenic integration), which included HBV integrations into the promoter (11.8%) and intron (47.1%). In contrast, non-tumor tissues more often showed intergenic integration (58.3%), with only intronic integration among all of the genic integrations (Fig. 2B). In particular, despite the lower total number of tumoral versus non-tumoral integration breakpoints, the tumors tended to harbor a greater proportion of genic integrations than the non-tumor samples (P=0.362), with the specific involvement of promoter-integrations, which was not seen in the adjacent non-tumor tissues.

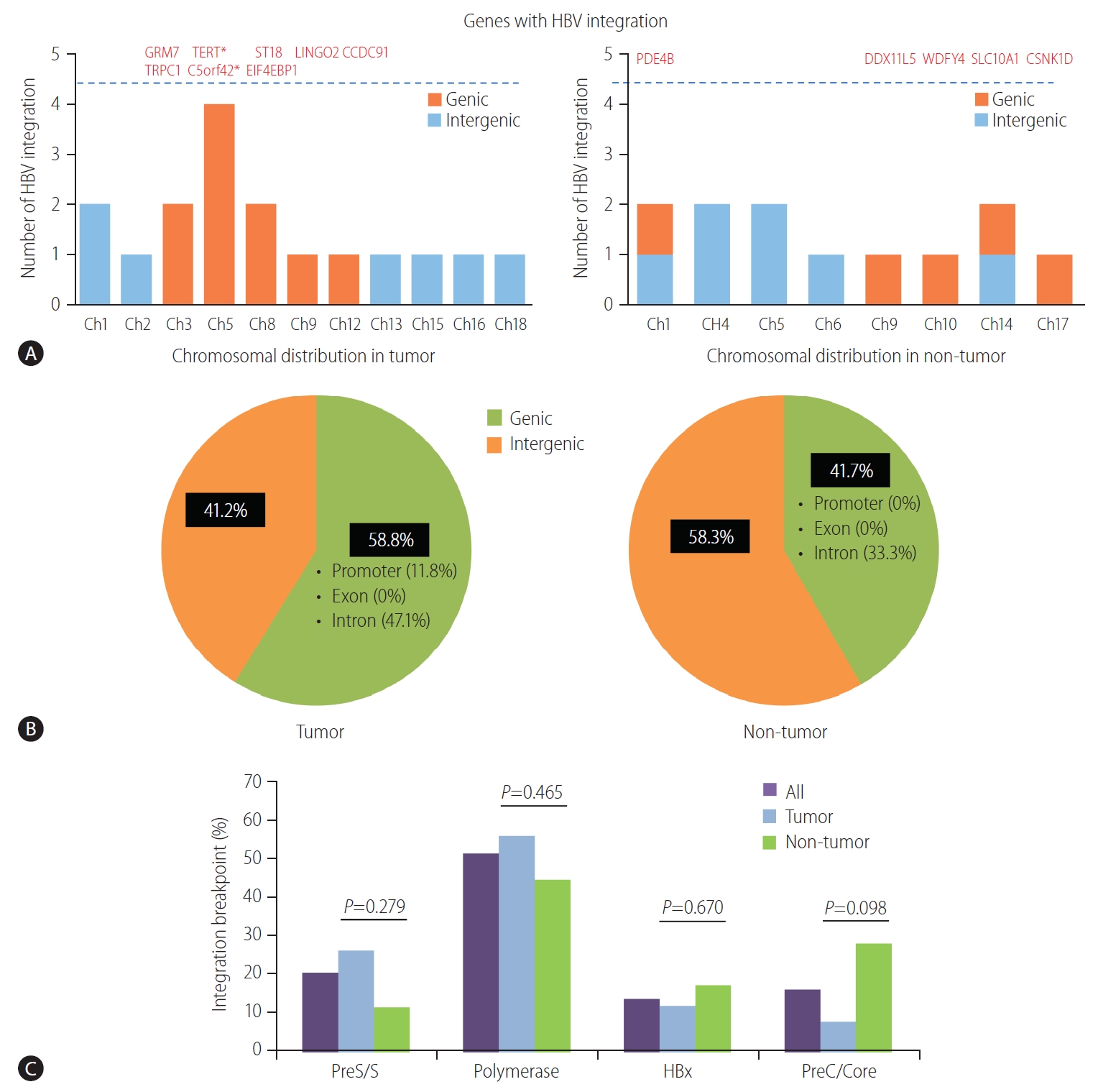

Overall, a total of 13 non-redundant genes with HBV integration are listed in Table 2. Among them, the TERT promoter region and chromosome 5 open reading frame 42 (C5orf42) at chromosome 5 were recurrently affected by HBV integration. The two genes with recurrent HBV integrations were detected exclusively in the tumor samples (Table 2). Notably, no gene was shared between tumors and non-tumors. Regarding functions of the affected genes, the tumoral genes with HBV integration were mostly involved in cell signaling, transcriptional regulation, development, metabolism, cell aging, and immortalization, which have been reported to be potentially involved in carcinogenesis (Table 3). Figure 3 illustrates a representative case of HBV integration (Pt #6 with HBV integration into the TERT promoter).

The locations of HBV integration into the HBV genome are shown in Figure 2C. The integrated HBV DNA breakpoints in all samples were distributed across the four HBV open reading frames, with a percentage frequency of 20.0%, 51.1%, 13.3%, and 15.6% in the surface, polymerase, X, and precore/core proteins, respectively (Table 2). The integration of HBV PreS/S gene sequences was observed more often in the tumor versus non-tumor samples, but the trend was not statistically significant (25.9% vs. 11.1%; P=0.279). In contrast, the integration of PreC/Core gene sequences tended to be more frequent in the non-tumors than in the tumors (P=0.098; Fig. 2C).

Study results of HBV integration may vary depending on the reference HBV genome used to capture the HBV sequences. Many previous studies of integration have included heterogeneous subjects in terms of HBV genotypes. In this regard, Korean patients are likely the best group to study HBV genome as genotype C is the universal type, accounting for almost 100% of Korean CHB patients [12]. Southern blot hybridization, an initial method for detecting integrated DNAs, was shown to have low sensitivity and only detected clones undergoing extensive positive selection. PCR-based methods are significantly biased toward Alu or other specific sequences. NGS-based technologies currently emerged for this purpose. However, whole-exome sequencing captures only coding regions, while robust detection by ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing is limited to HBV DNA integrations occurring in transcriptionally active sites or large cellular clones [3]. Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) also has some drawbacks including low depth and high cost, necessitating more efficient and cost-effective ways to identify viral integrations [3]. Recently, we developed a probe set expected to cover almost all of the putative genotypes of Korean HBV, as our probes were designed based on the eight full-length HBV genome sequences from Korean patients with various stages of liver disease. Moreover, our method permits ultra-high depth sequencing and unbiased HBV capturing at about one-fourth of the cost of WGS. Taking advantage of its utility, we were able to localize multiple HBV integration sites throughout the genome of even patients with HBsAg seroclearance.

The current study demonstrated that HBV integration into the host genome is still present either in tumor or non-tumorous tissues in most of the patients who lost HBsAg. This prevalence appeared to be clearly higher than that of HBsAg-negative HCC patients with different etiologies [4,5] and almost comparable to the reported data using NGS-based methods for those with overt HBV infections [3,13,14]. Importantly, our findings confirm the results of animal studies in clinical settings [7,8], which reported viral persistence as integrated forms after the resolution of HBV infection.

It is unclear whether these persistent HBV integrants contribute to liver cancer risk in functionally-cured patients with HBsAg seroclearance. The information has been lacking due to the widespread rarity of HBsAg seroclearance and the more extreme difficulties in obtaining tissues from such patients in order to study integration. The importance of our results lies in that we revealed a high prevalence of HBV integrations in the liver of patients who lost HBsAg. Moreover, the common site of HBV integration was the TERT promoter, in which a mutation was recently suggested as a gate-keeper driver in HCC development [15]. Overall, the study results demonstrated that the genomic locations of integration, as well as HBV inserts, often appeared to be enriched within the regions relevant to hepatocarcinogenesis. These findings may provide insight into the potential causal relationship between the intrahepatic persistence of HBV integrants and HCC in HBsAg seroclearance settings.

It is noteworthy that there were distinct integration features between the tumors and non-tumors. We detected more frequent overall integration, but less frequent genic HBV integration in the non-tumors rather than in the tumors. In addition, many tumoral integrations were located in the vicinity of regulatory or cancer-associated genes including TERT, which involve immortalization, cell signaling, development, and transcriptional regulation (Table 3). Viral breakpoints were also frequently found within or near the PreS/S gene, with some integrations in the X genes. The overall findings indicate that an HBV integration event in HCC with HBsAg seroclearance is absolutely comparable to that of HCC with overt HBV infection in terms of its genomic locations and viral inserts, as previously reported [2,13,16].

HBV integration reportedly occurs randomly throughout the human genome [2,3]. However, recent high-throughput data consistently demonstrated that HBV integration in HCCs was not random, with several specific, highly affected sites, such as TERT, MLL4, and CCNE2 [3,13,16]. Our analysis also showed HBV-TERT integration in our patient samples. Indeed, we observed biased, uneven chromosomal and genomic distributions of the HBV breakpoints, of which tumoral integrations were highly enriched in cancer-associated genes. As with HBV-related HCCs, the HBV integration sites in HCCs following HBsAg loss may reflect selection of integrations that confer a growth advantage to clonal populations of cells during liver carcinogenesis [2].

Our results emphasize HCC surveillance in chronic carriers achieving seroclearance. In our data, patients with HBsAg loss who did not remain under regular surveillance eventually presented with a large HCC (Table 1). A Korean study has shown that the estimated annual incidence rates of HCC following seroclerance were 2.85% and 0.29% in cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients, respectively [17]. The regional guidelines recommend offering surveillance when the risk of HCC exceeds 1.5%/year in cirrhotic patients and 0.2%/year in non-cirrhotic CHB patients [1,18]. Our analysis herein also showed the persistence of HBV integration within cancer-associated genes as well as HBV PreS/S subgenomic integrants in HCC patients achieving seroclearance. Thus, these findings strongly support ongoing HCC surveillance in patients even after HBsAg seroclearance.

Interestingly, we observed a higher number of integration breakpoints in HCC patients with detectable HBV DNA than in those with undetectable HBV DNA (Fig. 1C). The linear correlation between HBV breakpoints and HBV viremia status or OBI levels remains to be further confirmed. It would also be interesting to investigate the ŌĆśdirectŌĆÖ transforming effects of HBV integration in the absence of cirrhosis, as previously described [4,13]. The study subjects were all male. Besides HBV effects, gender or environmental/behavioral effects cannot be excluded in such patients. Since this study had only small sample sizes, it was not feasible to provide a detailed evaluation of such open questions. Nevertheless, our observation of HBV integrations enriched in cancer-related pathways, HBV PreS/S or X integrants, as well as cirrhotic patients with viremia, indicates that the direct and indirect pathways are not mutually exclusive but both may induce hepatocarcinogenesis in these settings.

In conclusion, our study clearly demonstrated the persistence of intrahepatic HBV DNA integration in HCC developing after HBsAg seroclearance. Using the Korean genotype-specific probe capture assay followed by NGS technology, we identified more frequent genic integrations in HCC with preferential sites toward cancer-associated genes, such as the TERT promoter, as well as subgenomic HBV fragments of regulatory elements, such as the PreS/S and X genes. These findings suggest that the biological functions of HBV integration would be absolutely comparable between HBsAg-positive and HBsAg-serocleared HCC and pro-oncogenic effects of HBV integration may continue and ultimately lead to HCC in a subset of patients achieving HBsAg seroclearance. Thus, ongoing HCC surveillance and clinical management should be continued even after HBsAg seroclearance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no financial or personal relationships with other persons or organizations that could inappropriately affect the work. Jeong Won Jang has served as a consultant to or has served on the advisory board of BMS, Gilead, AbbVie, and Bayer. Lewis R. Roberts has received grant funding from Bayer, Boston Scientific, Exact Sciences, Gilead Sciences, GlycoTest, RedHill Biopharma, TARGET PharmaSolutions, and Fujifilm Medical Systems USA, and served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, QED Therapeutics, and TAVEC.

FOOTNOTES

AuthorsŌĆÖ contribution

Study concept and design: Jang JW

Acquisition of data: Nam H, Sung PS, Bae SH, Choi JY, Yoon SK

Analysis and interpretation of data: Kim JS, Kim HS, Tak KW Experiment: Kim JS, Kim HS

Drafting and review of the manuscript: Jang JW, Roberts LR Study supervision: Jang JW

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no financial or personal relationships with other persons or organizations that could inappropriately affect the work. Jeong Won Jang has served as a consultant to or has served on the advisory board of BMS, Gilead, AbbVie, and Bayer. Lewis R. Roberts has received grant funding from Bayer, Boston Scientific, Exact Sciences, Gilead Sciences, GlycoTest, RedHill Biopharma, TARGET PharmaSolutions, and Fujifilm Medical Systems USA, and served on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Exact Sciences, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, QED Therapeutics, and TAVEC.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Clinical and Molecular Hepatology website (http://www.e-cmh.org).

Supplementary┬ĀFigure┬Ā1.

(A) Probes to capture integrated HBV sequences were designed from eight Korean genotype-specific full-length HBV genomes as listed in Supplementary Figure 1A and biotin-labeled. (B) The schematic view of probe-based HBV capture assay to detect HBV integration. The overall processes were prepared and modified based on Li et al [11]. HBV, hepatitis B virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Supplementary┬ĀTable┬Ā2.

PCR conditions for the human-HBV chimeric sequence amplification in case #patient 6: PCR optimization

Supplementary┬ĀTable┬Ā3.

Primer design on the human-HBV chimeric sequences in case #Patient 6

Figure┬Ā1.

Detection of HBV integration breakpoints. (A) Overall percentage of HBV breakpoints in tumors and non-tumors (P>0.999, FisherŌĆÖs exact test). Number of HBV breakpoints per sample in (B) tumors and non-tumors (P=0.369), and (C) samples with and without detectable HBV DNA (P=0.513). HBV, hepatitis B virus.

Figure┬Ā2.

(A) Distribution of HBV integration breakpoints across human chromosomes. The genes affected by HBV integration are listed above the dotted line. (B) Pie charts: proportion of HBV integration in the genic and intergenic regions of tumors and non-tumors. (C) HBV integration sites in the HBV genome. HBV, hepatitis B virus; TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase; Ch, chromosome. *Genes with recurrent HBV integration.

Figure┬Ā3.

Sanger sequencing validation of a representative case (Patient #6). (A) Detection of HBV integration (arrows). Additional information is provided in Supplementary Table 2. (B) Schematic view of the chimeric junction between human DNA and HBV DNA. (C) Sequences on both sides of the junction between human DNA (TERT promoter) and HBV DNA insert (HBV genome nt 2,612-2,650). The HBV sequences are underlined. HBV, hepatitis B virus; TERT, telomerase reverse transcriptase.

Table┬Ā1.

Baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients

| Patient | Sex | Age (years) | HBsAb | HBeAg/Ab | Anti-HBc | Serum HBV DNA (range*) | Antiviral therapy | Time to HCC (months) | Tumor size (cm) | Tumor differentiationŌĆĀ | Non-tumor liver | HCC surveillance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt #1 | Male | 63 | ŌĆō | ŌĆō/ŌĆō | + | Undetectable | No | 50 | 1.2 | Total necrosis | CirrhoticŌĆĪ | Regular |

| Pt #2 | Male | 57 | ŌĆō | ŌĆō/+ | + | Detectable (54ŌĆō695) | On lamivudine | 6 | 1.5 | II | CirrhoticŌĆĪ | Regular |

| Pt #3 | Male | 48 | ŌĆō | ŌĆō/+ | + | Undetectable | No | 41 | 1.2 | II | CirrhoticŌĆĪ | Regular |

| Pt #4 | Male | 43 | ŌĆō | ŌĆō/ŌĆō | + | Detectable (<10ŌĆō169) | No | 59 | 10.0 | III | Cirrhotic | Inadequate |

| Pt #5 | Male | 73 | ŌĆō | ŌĆō/+ | + | Detectable (10ŌĆō28) | No | 176 | 7.8 | III | Non-cirrhotic | No |

| Pt #6 | Male | 67 | + | ŌĆō/+ | + | Detectable (21ŌĆō140) | Prior lamivudine | 19 | 15.0 | II | Cirrhotic | Inadequate |

| Pt #7 | Male | 58 | ŌĆō | ŌĆō/+ | + | Detectable (<10ŌĆō62) | No | 88 | 15.8 | NA | Non-cirrhotic | No |

Table┬Ā2.

HBV integration loci of the 10 samples with HBsAg seroclearance

Table┬Ā3.

Target genes with HBV integration in the tumor tissues

Abbreviations

CHB

chronic hepatitis B

HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

HBV

hepatitis B virus

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

MLL4

mixed-lineage leukemia 4

MQ

mapping quality

NGS

next generation sequencing

OBI

occult HBV infection

PCR

polymerase chain reaction

TERT

telomerase reverse transcriptase

WGS

whole-genome sequencing

REFERENCES

1. Korean Liver Cancer Association; National Cancer Center. 2018 Korean Liver Cancer Association-National Cancer Center Korea practice guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut Liver 2019;13:227-299.

2. Bonilla Guerrero R, Roberts LR. The role of hepatitis B virus integrations in the pathogenesis of human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2005;42:760-777.

3. Budzinska MA, Shackel NA, Urban S, Tu T. Cellular genomic sites of hepatitis B virus DNA integration. Genes (Basel) 2018;9:365.

4. Wong DK, Cheng SCY, Mak LL, To EW, Lo RC, Cheung TT, et al. Among patients with undetectable hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatocellular carcinoma, a high proportion has integration of HBV DNA into hepatocyte DNA and no cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:449-456.

5. Tamori A, Nishiguchi S, Kubo S, Narimatsu T, Habu D, Takeda T, et al. HBV DNA integration and HBV-transcript expression in non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. J Med Virol 2003;71:492-498.

6. Yeo YH, Ho HJ, Yang HI, Tseng TC, Hosaka T, Trinh HN, et al. Factors associated with rates of HBsAg seroclearance in adults with chronic HBV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2019;156:635-646 e9.

7. Summers J, Mason WS. Residual integrated viral DNA after hepadnavirus clearance by nucleoside analog therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:638-640.

8. Tu T, Budzinska MA, Shackel NA, Urban S. HBV DNA integration: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Viruses 2017;9:75.

9. Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, Cacciola I, Raffa G, Craxì A, et al. Hepatitis B virus maintains its pro-oncogenic properties in the case of occult HBV infection. Gastroenterology 2004;126:102-110.

10. Jang JW, Choi JY, Kim YS, Woo HY, Choi SK, Lee CH, et al. Long-term effect of antiviral therapy on disease course after decompensation in patients with hepatitis B virus-related cirrhosis. Hepatology 2015;61:1809-1820.

11. Li W, Zeng X, Lee NP, Liu X, Chen S, Guo B, et al. HIVID: an efficient method to detect HBV integration using low coverage sequencing. Genomics 2013;102:338-344.

12. Kim BK, Revill PA, Ahn SH. HBV genotypes: relevance to natural history, pathogenesis and treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther 2011;16:1169-1186.

13. Sung WK, Zheng H, Li S, Chen R, Liu X, Li Y, et al. Genome-wide survey of recurrent HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet 2012;44:765-769.

14. Zhao LH, Liu X, Yan HX, Li WY, Zeng X, Yang Y, et al. Genomic and oncogenic preference of HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun 2016;7:12992.

15. Pinyol R, Tovar V, Llovet JM. TERT promoter mutations: gatekeeper and driver of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2014;61:685-687.

16. Li X, Zhang J, Yang Z, Kang J, Jiang S, Zhang T, et al. The function of targeted host genes determines the oncogenicity of HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2014;60:975-984.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- ORCID iDs

-

Jeong Won Jang

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3255-8474Lewis R. Roberts

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7885-8574 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Supplement1

Supplement1 Print

Print