A cost-effectiveness study of universal screening for hepatitis C virus infection in South Korea: A societal perspective

Article information

Abstract

Background/Aims

This study aimed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening compared to no screening in the Korean population from societal and healthcare system perspectives.

Methods

A published decision-tree plus Markov model was used to compare the expected costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALY) between one-time universal HCV screening and no screening in the population aged 40–65 years using the National Health Examination (NHE) program. Input parameters were obtained from analyses of the National Health Insurance claims data, Korean HCV cohort data, or from the literature review. The population aged 40–65 years was simulated in a model spanning a lifetime from both the healthcare system and societal perspectives, which included the cost of productivity loss due to HCV-related deaths. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) between universal screening and no screening was estimated.

Results

The HCV screening strategy had an ICER of $2,666/QALY and $431/QALY from the healthcare system and societal perspectives, respectively. Both ICERs were far less than the willingness-to-pay threshold of $25,000/QALY, showing that universal screening was highly cost-effective compared to no screening. In various sensitivity analyses, the most influential parameters on cost-effectiveness were the antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) prevalence, screening costs, and treatment acceptance; however, all ICERs were consistently less than the threshold. If the anti-HCV prevalence was over 0.18%, screening could be cost-effective.

Conclusions

One-time universal HCV screening in the Korean population aged 40–65 years using NHE program would be highly cost-effective from both healthcare system and societal perspectives.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major cause of liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and liver-related mortality. Globally, there were 5.8 million people living with HCV infection in 2019, accounting for 0.75% of the entire population [1]. The estimated number of newly infected people (1.75 million) exceeded the estimated number of people dying from HCV infection (399,000) and those being cured (843,000) in 2015 [2]. Therefore, without prevention and treatment, HCV-related mortality seems to increase.

The introduction of highly efficacious direct acting antivirals (DAAs) resulted in achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR) of >90% after 8–12 weeks of treatment, which is considered a “cure.” SVR has been shown to reduce the incidence of HCC by an estimated 85% and liver-related mortality and all-cause mortality by 70–75% in individuals with or without cirrhosis [3-5]. Therefore, the World Health Organization (WHO) called for the elimination of viral hepatitis B (HBV) and C infections as a public health problem at a 90% reduction in incidence (95% for HBV and 80% for HCV) and 65% reduction in mortality by 2030, compared to the 2015 baseline. In 2021, the WHO interim guidance used the following absolute impact targets for hepatitis elimination: an absolute annual HCV incidence of ≤5/100,000 people or ≤2/100 people who inject drugs (PWID); an HCV-related annual mortality rate of ≤2/100,000 people. These targets should be accomplished by testing >90% of the HCV diagnosed, treating >80% of diagnosed patients, and preventive measures including 0% unsafe injections, 100% blood safety, and 300 needles/syringes/PWID per year [1].

HCV accounted for 10–20% of the cause of liver cirrhosis and HCC in South Korea. The prevalence of antibodies to HCV (anti-HCV) in the Korean adult population was 0.78% in 2009 and 0.6% in 2015, showing increasing prevalence according to age [6]. Therefore, about 90% of chronic HCV patients were aged over 40 years. Considering that Korea is a region with low HCV prevalence in the global perspective, with a highly effective system for disease screening by the National Health Examination (NHE) program (Supplementary Table 1) run by the government [7], HCV eradication is highly feasible.

Previous studies on the screening of the Korean population with a high prevalence of HCV (age 40–60 years) using the NHE system were robustly cost-effective from the healthcare system perspective [8-10]. However, no study has been conducted on the cost-effectiveness of these screening strategies from a societal perspective. In addition, the treatment cost or duration and disease epidemiology is rapidly evolving; thus, for a national plan for HCV elimination and cost-effectiveness update from a healthcare perspective is needed [11,12]. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the cost-effectiveness of universal anti-HCV antibody screening in the Korean population aged 40–65 years as a part of NHE compared to no screening, from both healthcare system and societal perspectives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Overview of the cost-effectiveness model

A cost-utility analysis was conducted to compare the “one-time universal screening in the Korean population aged 40–65 years using anti-HCV,” provided as a part of the NHE program, to “no screening.”

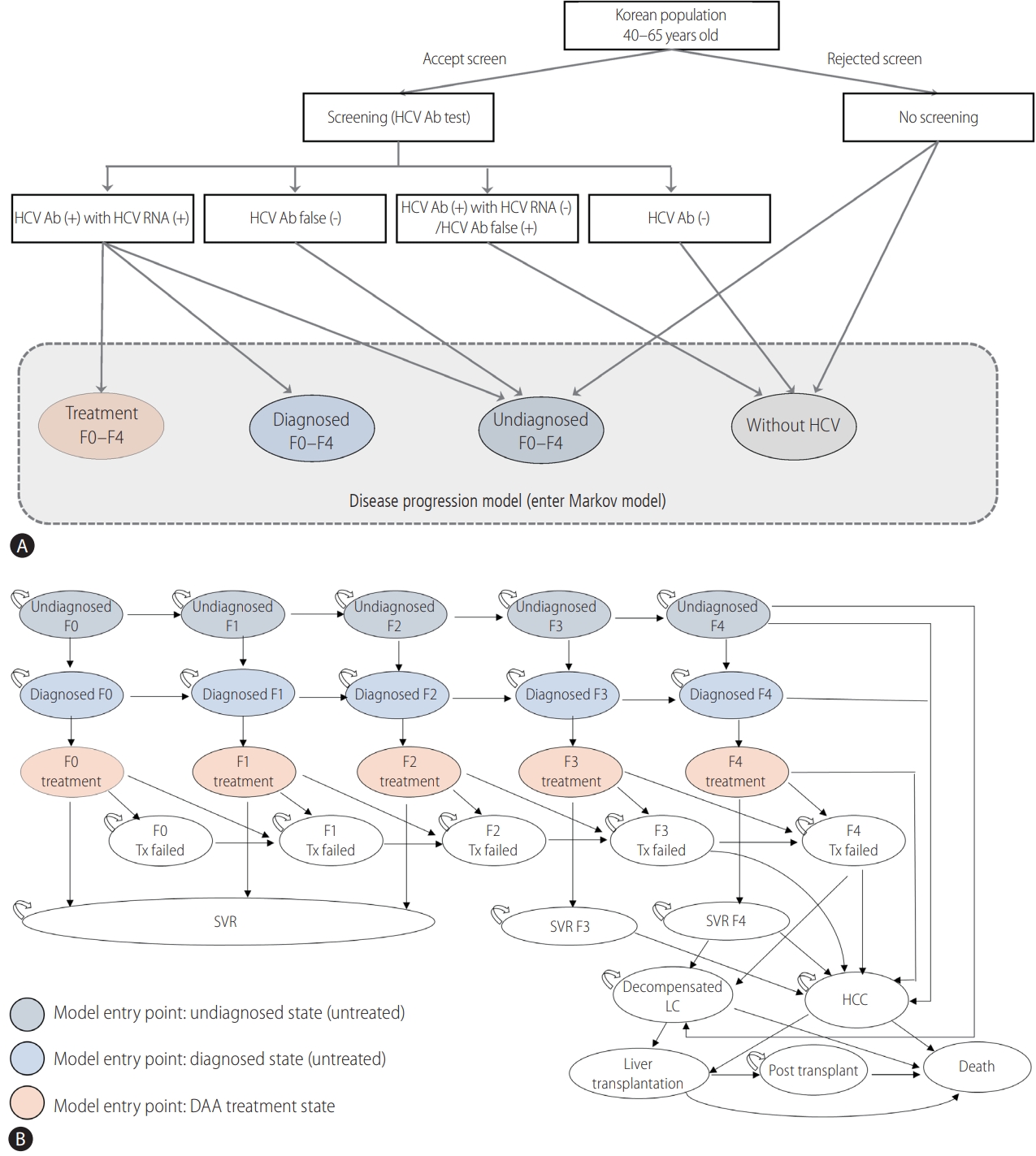

An established model reflecting the actual clinical setting and natural history of HCV infection was used, which was developed with the TreeAge Pro program (TreeAge Software, Williamstown, MA, USA) [9]. Some input parameters were updated, and the model was partially modified to reflect current practices such as prescribing trends and reduced prices of DAA agents. The model had two parts: a decision tree model and a Markov model. In the decision tree model, the population was divided into subgroups of “treatment state (F0-F4),” “diagnosed state (F0-F4),” “undiagnosed state (F0-F4),” and “alive without HCV” according to the prevalence of HCV antibodies, test performance of HCV antibody, HCV RNA positivity, and acceptance rates of screening and treatment (Fig. 1A). Then, the population was entered into the Markov model and moved to 28 predefined health states, including chronic hepatitis with fibrosis stage 0–3, compensated cirrhosis (F4), decompensated cirrhosis (DC), HCC, SVR, and liver transplantation (LT). In every health state, patients were at the risk of death from non-liver disease (age-related mortality) or liver disease (disease-specific mortality in DC, HCC, or LT). The cycle length of the Markov model was 1 year, and the lifetime horizon was selected. In each cycle, patients either remained in their current health state (recursive arrow) or progressed to another health state (straight arrow) according to the transition probability (Fig. 1B).

Cost-effectiveness model including (A) decision tree model and (B) Markov model. The model has two parts: (A) decision tree model and (B) Markov model. (A) Populations were divided into subgroups according to screening, diagnosis, and treatment. (B) Populations were entered into the Markov model and moved to 28 predefined health states, including chronic hepatitis (F stage 0–3), compensated LC (F4), decompensated cirrhosis (DC), HCC, SVR, and liver transplantation, and death by each transition probability. The cycle length of the Markov model was 1 year, and the lifetime horizon was chosen. In each cycle, patients either remained in their current health state (recursive arrow) or progressed to another health state (straight arrow) according to the transition probability. HCV, hepatitis C virus; Tx, treatment; SVR, sustained virologic response; LC, liver cirrhosis.

The following assumptions were made in our analysis. 1) Only one-time screening for HCV infection was provided to the Korean population aged 40–65 years during the biannual NHE. 2) Half of the patients were treated in the year of diagnosis, while the other half were treated in the following year. 3) Patients diagnosed from screening would have mild or no symptoms; hence, there were no symptomatic cases of decompensated liver cirrhosis at the time points of simulation entry. 4) Although there is insufficient data on HCV re-infection, it is considered to be very rare in Korea. Therefore, we assumed an absence of re-infection in our model.

Input parameters and data source

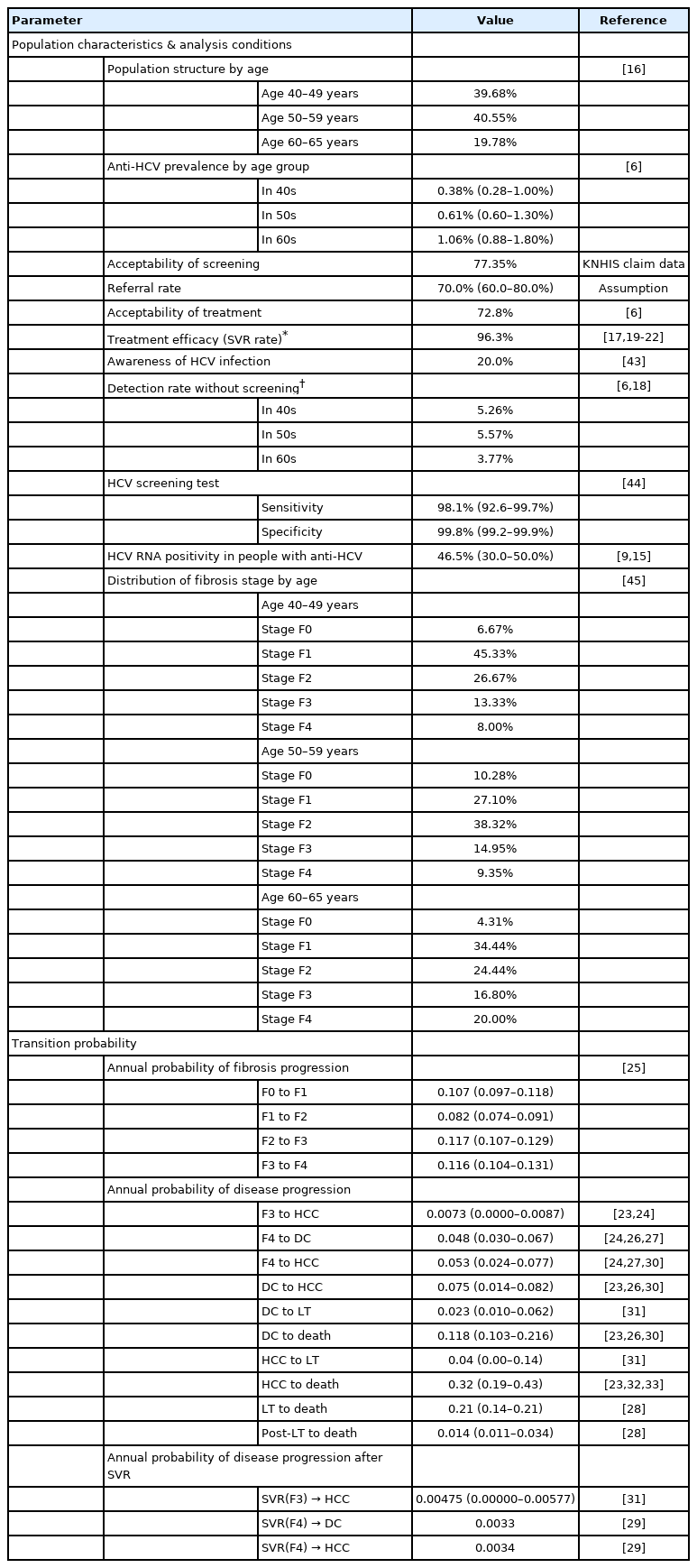

Studies in South Korea and other countries on epidemiology and treatment effects on patients with chronic HCV, analysis of health insurance claim data, and government statistics were extensively used. The optimal values were determined after discussion with the researchers. Data from South Korea were primarily used. The input parameters used in the model are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2.

Screening performance and other analysis conditions

Screening was performed by testing anti-HCV with 98.1% sensitivity and 99.8% specificity. The assumed acceptance rate of screening was 77.4% based on a report from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (KNHIS) [14]. HCV viremia was estimated to be present in 46.5% of people showing a positive anti-HCV [9,15]. The population structure by age was extracted from the 2019 population census [16]; the prevalence of anti-HCV by age group was estimated to be 0.38%, 0.63%, and 1.06% in 40s, 50s, and 60s, respectively [6]. The annual detection rate of HCV infection without screening was applied as 3.8–5.6% [17,18].

The current prescription profiles of various DAA regimens were estimated using the data extracted from the 2019 Korean HCV cohort study. Specifically, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for 8 weeks was the most commonly prescribed regimen (74.8%), followed by ledipasvir/sofosbuvir (11.2%), elbasvir/grazoprevir (10.5%), and sofosbuvir and ribavirin (3.5%) for 12 weeks each. The SVR rates of each regimen were obtained from the literature review [17,19-22].

Transition probabilities for movement between health states were determined as the best optimal values by authors through previous literature reviews or from the Korean government databases [23-34].

Costs and quality of life

The direct medical costs related to each health state were extracted from the KNHIS claim data analysis and reimbursement price list from HIRA. Direct medical costs included total fees for hospitalization, consultation, medication, examination, and other management. The operational definitions for each health state to estimate medical costs using claims data are presented in Supplementary Table 3. Indirect costs associated with productivity loss due to premature deaths were calculated using the average number of working days, average wage, and employment rate by age group from the Korean government database. Transportation costs resulting from hospital visits were also estimated according to the health states. All costs were measured in Korean won (KRW) and adjusted for inflation using the Korean consumer price index to reflect the 2020 KRW; they were converted to United States dollars ($) using the annual average currency rate in 2020 ($1=1,180 KRW) (Supplementary Table 3).

Utility weights for health states were obtained from published studies [9,23,26]. Age-specific utility weights in the general population were derived from the EQ-5D values in the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2018 (Supplementary Tables 2, 4).

Analysis

The main output was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of the “universal HCV screening” strategy compared to the “no screening” strategy. The ICER was calculated by dividing the incremental costs by the incremental QALY (or LY) between the comparative strategies. When the estimated ICER was less than $25,000/QALY, implicitly accepted as a willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold in Korea, the universal screening was considered to be cost-effective.

One-way deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analyses were performed to explore the uncertainty of the input parameters and applied assumptions. For one-way sensitivity analyses, the following variables related to HCV screening and the natural course of HCV infection were included: the prevalence of anti-HCV, detection rate without HCV screening, age, acceptability of treatment, SVR rate of DAA therapy, test fee, medical cost, utility weight, and discount rate.

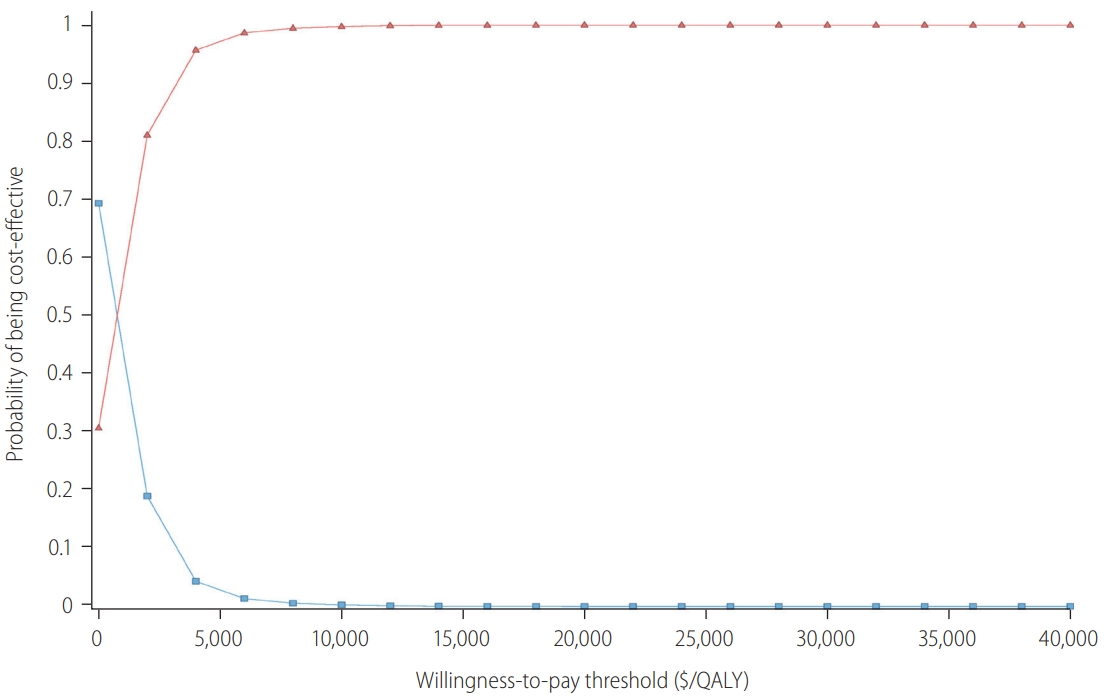

A probabilistic sensitivity analysis, using a second-order Monte Carlo simulation, was performed to evaluate the overall effect of uncertainty. The simulation was run 10,000 times with parameter values randomly generated from the relevant distributions. We applied a beta distribution for transition probabilities and utility weights and a gamma distribution for the costs (Supplementary Table 5). The results are presented as a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC).

RESULTS

Base-case analysis

In the base-case analysis from a healthcare system perspective, including direct medical costs, the universal HCV screening and DAA treatment group gained 0.0014 QALY (and 0.0010 LY) per patient compared to the “no screening” group over the lifetime horizon. The difference in the total costs per patient was $3.6, and the estimated ICER were $2,666/QALY and $3,653/LY (Table 2).

The cost-effectiveness results from a societal perspective, including the cost of productivity loss due to premature deaths and transportation cost, as well as direct medical costs, showed that universal HCV screening and DAA treatment compared to no screening would raise the QALY by 0.0014 (and LY by 0.0010) and the cost by $0.58, resulting in an ICER of $431/QALY and $590/LY. Therefore, the results from the societal perspective showed lower ICER than those from the healthcare system perspective. As the estimated ICERs ($2,666/QALY and $431/QALY) were far less than the threshold of $25,000/QALY, universal screening was highly cost-effective compared to the no screening strategy.

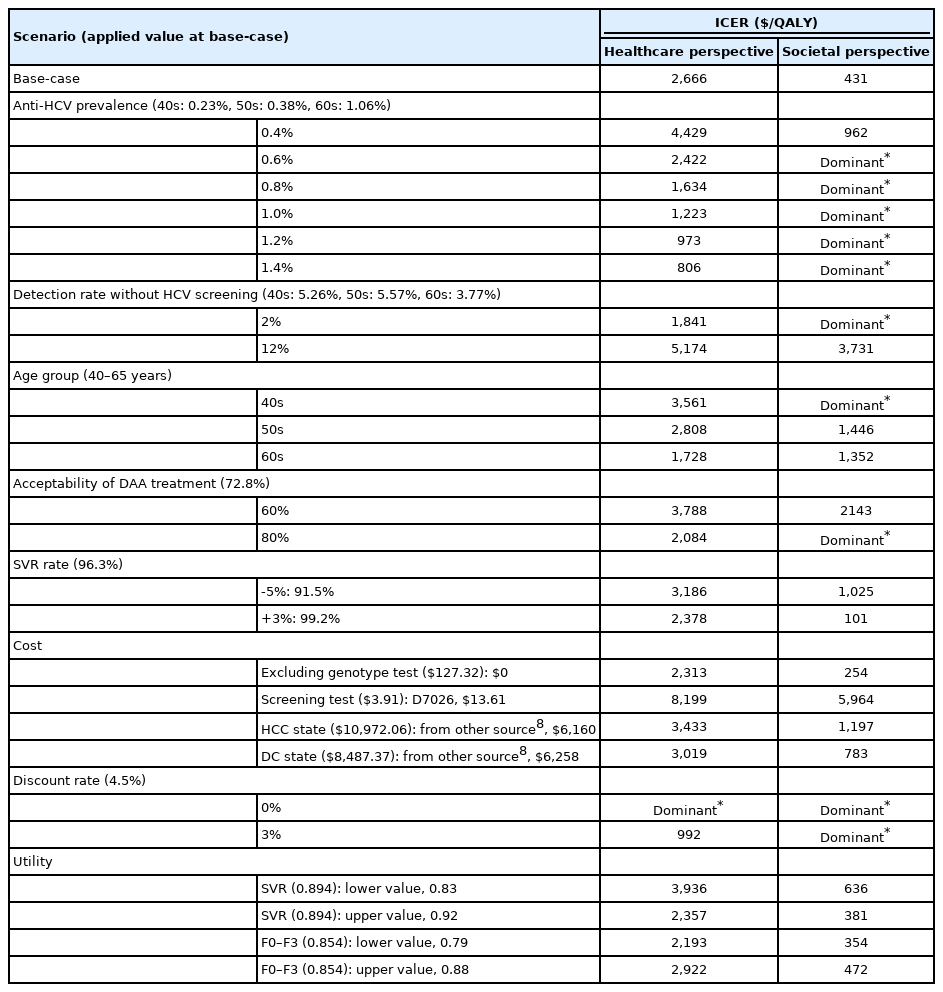

One-way sensitivity analysis

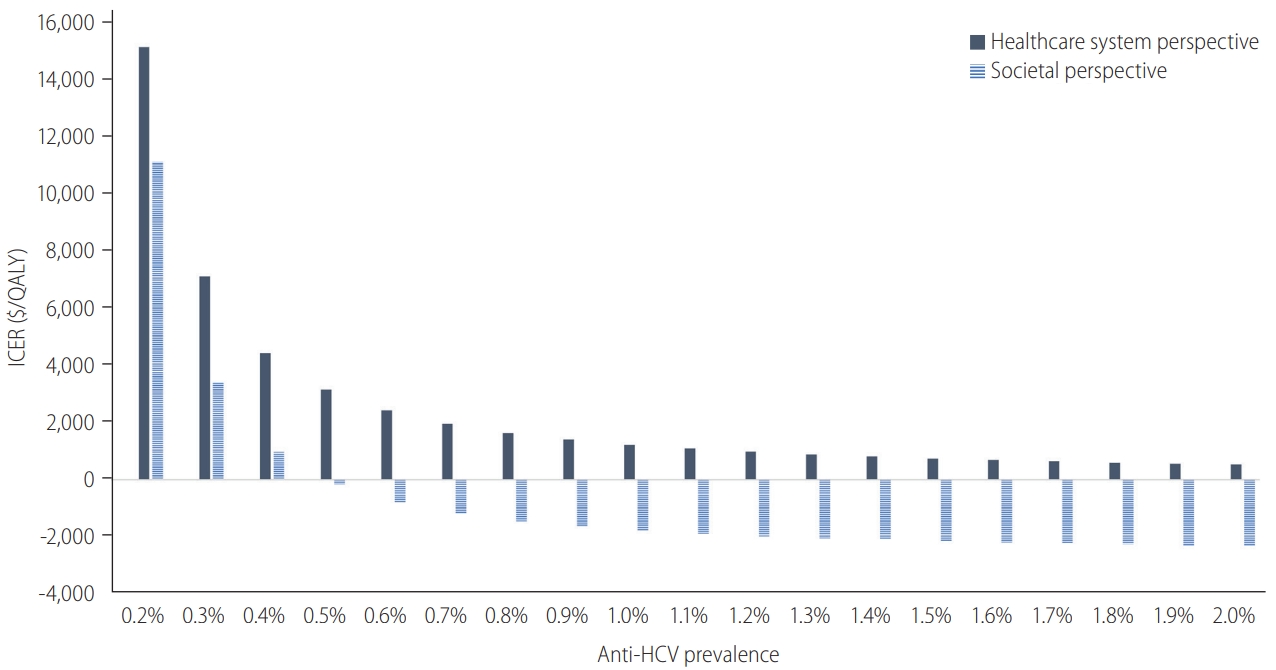

The results of the one-way sensitivity analyses are presented in Table 3 and Figure 2. The most influential parameter on the ICERs was the anti-HCV prevalence. As the prevalence of anti-HCV antibodies increased, the ICER decreased remarkably (Fig. 2). The changes in ICER according to various anti-HCV prevalence are shown in Figure 3; in the analysis from a healthcare system perspective, the ICER was $15,170/QALY with 0.2% anti-HCV prevalence and $527/QALY with 2.0% of it. Similarly, in the analysis from a societal perspective, the trend of ICER changed according to anti-HCV prevalence. With the anti-HCV prevalence over 0.179–0.186%, universal screening was cost-effective (ICER <$25,000/QALY) from both the healthcare system and societal perspectives (Fig. 3).

One-way sensitivity analysis presented through a tornado diagram. The most influential parameter on the ICERs was anti-HCV prevalence, showing that the ICER decreased remarkably as the prevalence of anti-HCV increased. This was followed by the screening cost according to the different immunoassay tests. Other variables affecting the ICERs included the detection rate without HCV screening, discount rate, acceptance rate of DAA treatment, utility weight for SVR, cohort age, SVR rate of DAA agent, utility weight for F0–F3, medical costs for HCC and DC, and HCV genotype testing. ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life years; HCV, hepatitis C virus; DAA, direct acting antiviral; Tx, treatment; SVR, sustained virologic response; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; DC, decompensated cirrhosis.

Changes in ICERs according to anti-HCV prevalence. The changes in ICER according to various anti-HCV prevalence are shown. From a healthcare system perspective, the ICER was $15,170/QALY with 0.2% anti-HCV prevalence and $527/QALY with 2.0% of it. Similarly, in the analysis from a societal perspective, the trend of ICER changed according to anti-HCV prevalence. With the anti-HCV prevalence over 0.179–0.186%, universal screening is cost-effective (ICER <$25,000/QALY) from both healthcare system and societal perspectives. ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY, quality-adjusted life years; anti-HCV, antibodies to hepatitis C virus.

Regarding the screening costs, it was observed that when the high-quality immunoassay test (National Health Insurance [NHI] fee code: D7026, $13.61) was substituted for the anti-HCV test (D7005, $3.91), the ICER increased to $8,199/QALY. Although our baseline anti-HCV test is adequate for population screening, many healthcare centers in Korea currently use the high-quality immunoassay test. For the detection rate without HCV screening, the ICER was $1,841/QALY with 2% and $5,174/QALY with 12% in the analysis from healthcare system perspective (in a societal perspective, -$0.54 and $3,731, respectively).

Other variables affecting the ICERs included the acceptance rate of DAA treatment, discount rate, utility weight for SVR, cohort age, SVR rate of DAA agent, utility weight for F0–F3, medical costs for HCC and DC, and HCV genotype testing.

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis

The results of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis simulated 10,000 times are illustrated in a CEAC (Fig. 4) and a cost-effectiveness scatter plot (Supplementary Fig. 1). CEAC indicated that the probability of a one-time screening and DAA therapy being cost-effective was 60.3%, 81.8%, and 97.7% with a WTP of $1,000, $2,000, and $5,000, respectively. In the cost-effectiveness scatter plot, the probability was 99.9% at a WTP threshold of $25,000. This confirmed the robustness of the cost-effectiveness of universal screening strategy.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. The results of the probabilistic sensitivity analysis simulated 10,000 times are illustrated. This indicates that the probability of a one-time screening and DAA therapy being cost-effective is 60.3%, 81.8%, and 97.7% with a WTP of $1,000, $2,000, and $5,000, respectively. QALY, quality-adjusted life years; DAA, direct acting antiviral; WTP, willingness-to-pay.

Health-related outcomes

Under the base-case analytic conditions, the one-time universal screening for Korean populations aged 40–65 years (total 21,099,926) was estimated to detect 32,148 HCV infection cases additionally. Moreover, it was estimated to reduce 4,081 HCV-related deaths over a lifetime (19.4/100,000). The number of preventable HCCs, DCs, and LTs over a lifetime was 3,156, 1,939, and 554, respectively (Supplementary Table 6).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that one-time universal screening with an anti-HCV test, provided as a part of the NHE program, and DAA treatment is highly cost-effective compared to no screening in the Korean population aged 40–65 years. In our results, an increase in QALY by 0.0014 and additional cost by $3.6 resulted in an ICER of $2,666/QALY from a healthcare system perspective. The results from a societal perspective, including the cost of loss of productivity by premature death related to HCV infection, showed lower ICER than that from the healthcare system perspective ($431/QALY). Both ICERs were calculated to be far less than $25,000, which is the implicit threshold of a WTP in Korea, based on the country’s gross domestic product per capita.

We conducted analyses from both the healthcare system and societal perspectives according to the recommendation for methodological practice by the panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine [35]. The report strongly emphasized that all cost-effectiveness analyses should report two analyses of both perspectives to improve quality and comparability. As shown in our study, results from a societal perspective generally have lower ICER than that from a healthcare system perspective, as the preventive cost can be covered not only in the healthcare sector, but also by employment and other sectors in society [36]. Therefore, in research dealing with disease in a relatively young population, the ICER difference between perspectives is greater.

The base-case analysis was simulated with 0.6% anti-HCV prevalence, and we showed that the estimated ICER could be maintained under the threshold even if the prevalence was lowered by 0.18%. Furthermore, universal screening prevented 19 HCV-related deaths, 15 HCCs, and nine DCs per 100,000 screened people. Although the expenses increased for HCV screening tests and DAA treatment in early diagnosed patients, the reduced health events that profoundly impacted medical expenses could be offset. Additionally, the robustness of cost-effectiveness for universal screening was demonstrated through the various sensitivity analyses to test the changes in the assumptions and input values of the model.

Our model was designed in a very sophisticated manner to reflect the actual conditions of the NHE program in Korea. NHI members over the age of 40 receive a biennial health examination from the NHIS; therefore, the model simulated that half of the population underwent examination in the current year and the other half in the following year. We also considered that half of the patients who accepted treatment would take medicine in the current year and the others in the following year, since not all patients receive treatment at once. Furthermore, the characteristics related to the medical utilization of the population, such as acceptability of screening and treatment, rate of clinic visits, and detection rate without screening, were applied to the model to reflect a real-world setting. Additionally, our analysis adopted the actual treatment proportion of DAA agents from the Korea HCV cohort study and the recent medical costs from representative data sources, such as the NHI claims data and NHI service fee table. Therefore, our results showed strong evidence for cost-effectiveness when HCV screening would be provided as part of the NHE program.

Our overall findings agree with previous studies that suggested the cost-effectiveness of universal HCV screening compared to no screening or risk-based screening in several countries [29,37-39]. In the economic evaluation studies of HCV screening for the Korean population, the universal screening was highly cost-effective as the estimated ICER was approximately $3,500–$9,000/QALY [8-10]. Cost-effectiveness varies depending on the healthcare system, medical service fees, treatment cost, and prevalence rate in each country [40]. Estimation of relatively lower ICERs from studies in Korea could be related to the cheaper medical service fees and DAA treatment cost. In particular, the DAA cost per course in Korea was $7,300–$18,500 according to the genotype just a few years ago, but the current cost is about $9,250 owing to a voluntary price cut by pharmaceutical companies since the advent of the pan genotypic DAA [41]. As a result, studies conducted after the price cut of DAA suggested a much lower ICER [8]. In addition to the price reduction of DAA, increased acceptance of DAA treatment and increased medical costs of severe health states, such as HCC and DC, led to a lower ICER compared to that seen in our previous work, although the same model was used [9].

Compared to our previous study, the estimated number of health events, such as HCV-related deaths, HCC, DC, and LT, decreased, and the number of preventable health outcomes (difference) between strategies was also reduced. This was attributed to changes in some input parameters. First, patients with advanced liver fibrosis decreased (F0–F2: 69.0% vs. 74.4%; F3–F4: 31.0% vs. 25.6%). Second, the acceptability of the treatment increased from 63.7% to 72.8%. Third, the detection rate without a screening changed from 0.8% to 3.8–5.3%, according to the age group. The two former variables influenced the reduction in the absolute number of events and the latter played a role in reducing the difference. Fourth, additional costs due to false-positive results of HCV screening tool (e.g., re-examination and transportation fee) were not applied to our model, as the anti-HCV test already showed very high sensitivity and specificity. Lastly, we simulated using a static (Markov) model instead of a dynamic model, which is known to be more suitable for infectious disease modelling. Dynamic models are important when an intervention affects a pathogen’s ecology or disease transmission. However, the scope of our research did not correspond to these situations. In addition, since a static model potentially underestimates the health effects of treatment, it provides a conservative estimate of cost-effectiveness [42].

By conducting additional analysis and partially modifying the analytic model, the current study overcame some limitations of our previous work. However, this study still had some limitations. First, several parameters related to the natural history of HCV infection were based on the literature and not fully defined. Second, the utility weights of patients with HCV infection were obtained from foreign data since there were no appropriate utility values for these health states for the Korean population. To assess the uncertainty of the input values and assumptions, we conducted extensive sensitivity analyses, which showed that the estimated ICERs were maintained robustly under the WTP threshold. Third, from a societal perspective, we only included the cost of productivity loss due to premature HCV-related deaths. The cost of unpaid lost productivity owing to illness or cost of uncompensated household production were not counted due to the absence of relevant information.

In conclusion, the one-time universal HCV screening with antiHCV test and DAA treatment was highly cost-effective compared to no screening in the Korean population aged 40–65 years. The cost-effectiveness was even higher from a societal perspective, which included the cost of productivity loss due to HCV-related deaths. As more pan genotypic DAAs are launched in the future, genotype testing could be omitted and the prices of antiviral treatment could fall owing to market competition, which would affect the ICER decline. Therefore, providing universal HCV screening as part of the NHE program can help achieve the goal of HCV elimination in South Korea.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by “The Research Supporting Program of The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver and The Korean Liver Foundation” and “The Chronic Infectious Disease Cohort Study (Korea HCV Cohort Study, 2020-E510400)” from Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency.

Notes

Authors’ contributions

Authors’ contributions All authors have full access to all data used in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The principal investigators SH Jeong was responsible for the conception and design of the study; the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data and the drafting of the manuscript. KA Kim and HL Kim, were responsible for the design of the study; the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data and the drafting of the manuscript. GH, Choi, ES Jang, M Ki, and HY Choi contributed to the literature search and data collection and assembly. All authors approved the definitive version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflicts of Interest

SH Jeong has served as an advisor for Gilead. The remaining authors disclose no conflicts.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Clinical and Molecular Hepatology website (http://www.e-cmh.org).

Summary of the national health examination program in South Korea

Input parameters (costs and utility weights)

Operational definitions

Applied utility weights to “without HCV population”6

Input parameters for probabilistic sensitivity analysis

Number of health events per 100,000 screened people

Cost-effectiveness scatter plot. In the cost-effectiveness scatter plot, the probability is 99.97% at a WTP threshold of $25,000. This confirms the robustness of the cost-effectiveness of universal screening strategy. QALY, quality-adjusted life years; WTP, willingness-to-pay.

Abbreviations

anti-HCV

antibodies to HCV

CEAC

cost-effectiveness acceptability curve

DAA

direct acting antiviral

DC

decompensated cirrhosis

HBV

hepatitis B virus

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

HCV

hepatitis C virus

HIRA

Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service of Korea

ICER

incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

KNHIS

Korean National Health Insurance Service

KRW

Korean won

LT

liver transplantation

LY

life years

NHE

National Health Examination

NHI

National Health Insurance

PWID

people who inject drugs

QALY

quality-adjusted life years

SVR

sustained virologic response

WHO

World Health Organization

WTP

willingness-to-pay

References

Article information Continued

Notes

Study Highlights

• The one-time universal HCV screening in the Korean population aged between 40–65 years with anti-HCV test and DAA treatment was highly cost-effective compared to no screening, from both healthcare system and societal perspectives.

• This screening strategy could prevent HCV-related deaths and development of HCC compared to no screening.

• The national action plan for HCV elimination until 2030 should include universal screening and enhanced linkage of care.