| Clin Mol Hepatol > Volume 29(Suppl); 2023 > Article |

|

See the commentary-article "The growing burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease on mortality" on page 374.

ABSTRACT

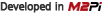

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in the United States and worldwide. Though nonalcoholic fatty liver per se may not be independently associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality, it is associated with a number of harmful metabolic risk factors, such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, and an unhealthy diet. The fibrosis stage is a predictor of all-cause mortality in NAFLD. Mortality in individuals with NAFLD has been steadily increasing, and the most common cause-specific mortality for NAFLD is cardiovascular disease, followed by extra-hepatic cancer, liver-related mortality, and diabetes. High-risk profiles for mortality in NAFLD include PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism, low thyroid function and hypothyroidism, and sarcopenia. Achieving weight loss through adherence to a high-quality diet and sufficient physical activity is the most important predictor of improvement in NAFLD severity and the benefit of survival. Given the increasing health burden of NAFLD, future studies with more long-term mortality data may demonstrate an independent association between NAFLD and mortality.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as hepatic steatosis in the absence of significant alcohol consumption or other alternative explanation for hepatic fat deposition, such as underlying other chronic liver diseases [1,2]. It is closely associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, obesity, gallstone disease, a sedentary lifestyle, and an unhealthy diet [3-5]. NAFLD is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in the United States, where prevalence passed over 30% in 2017ŌĆō2018 [6]. Prevalence of NAFLD is similarly high in other parts of the world, particularly the Middle East and South America [1]. While the prevalence of chronic viral hepatitis has decreased over the past decade, the prevalence of NAFLD has steadily increased over the same period, coinciding with increasing rates of obesity and type 2 diabetes [7,8]. The US national prevalence of NAFLD-related advanced fibrosis increased from 2.6% in 2005ŌĆō2008 and 4.4% in 2009ŌĆō2012 to 5.0% in 2013ŌĆō2016 [7]. Age-standardized mortality in individuals with NAFLD has also been steadily increasing over the past decade at an annual rate of 7.8% [9]. Though projected to further increase by 44% between now and 2030 [10], mortality for NAFLD still remains lower than those seen in chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection or alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) [9]. The most common cause-specific mortality in individuals with NAFLD is cardiovascular disease, followed by mortality due to extra-hepatic cancer, liver-related mortality (including hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC), and diabetes [11]. When controlling for comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, smoking status, hyperlipidemia, and obesity, NAFLD per se is not associated with increased allcause or cause-specific mortality, likely because a large proportion of this mortality is due to cardiovascular deaths driven by comorbid metabolic abnormalities [12,13]. In contrast, metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, which requires the presence of metabolic risk factors in the setting of hepatic steatosis, is associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality [13,14]. In this review, we focus on the causes and risk profiles of mortality among individuals with NAFLD (Fig. 1).

We summarized essential studies regarding all-cause mortality in individuals with NAFLD in Table 1. The first US community-based retrospective cohort study (n=435) of its kind showed there was a significantly lower survival for populations with NAFLD defined by ultrasonography or histology compared to the age- and sex-matched general population during 7.6 years of follow-up (77% vs. 87%, respectively, P<0.005) [15]. Several subsequent studies revealed similar results with a significant increase in all cause-mortality with ranges of the hazard ratio (HR) of 1.004ŌĆō1.038 and standardized mortality ratio of 1.34ŌĆō2.6 [16]. Although earlier studies showed that NAFLD was associated with a higher risk of allcause mortality compared to the general population of the same age and sex, it is unclear whether NAFLD-related liver disease is an independent risk factor, or if it is associated with the underlying metabolic abnormalities responsible for the increased risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortalities [17]. A US population-based study determined that NAFLD per se did not increase mortality risk after adjusting for multiple clinical and metabolic confounders beyond age and sex [12,13]. Consistent with these results, several studies have reported no significant difference in all-cause mortality in individuals with NAFLD [16,18,19]. Stratification by fibrosis using non-invasive panels was associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality [12]. A Swedish nationwide, matched cohort study with 10,568 biopsy-confirmed NAFLD reported that significant excess mortality risk was noted in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) without fibrosis (adjusted HR, 1.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.03ŌĆō1.26), non-cirrhotic fibrosis (adjusted HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.15ŌĆō1.38) and cirrhosis (adjusted HR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.75ŌĆō2.18) compared with nonalcoholic fatty liver (simple steatosis) [20]. Dose-response association along with the severity of NAFLD was observed (P for trend <0.01) [20]. A recent meta-analysis showed that compared with no fibrosis (stage 0), the unadjusted risk increased with increasing stage of fibrosis (stage 0 vs. 4) with all-cause mortality relative risk (RR) of 3.42 (95% CI, 2.63ŌĆō4.46) irrespective of the presence or absence of NASH [21]. The stage of fibrosis and rate of fibrosis development associated with mortality in NAFLD may be utilized as a predictor to differentiate between low-risk NAFLD and those that will progress to fibrosis or cirrhosis, which result in all-cause mortality. Therefore, better phenotyping of NAFLD may be needed to determine the relationship of NAFLD with all-cause mortality.

The recent trends in NAFLD-related all-cause mortality showed an initial linear increase, which then accelerated in recent years in the US [9,11]. Although the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision (ICD-10) code for NAFLD underestimated the true prevalence of NAFLD, the mortality due to NAFLD increased from an annual rate of 6.1% (95% CI, 4.5ŌĆō7.8%) in 2007ŌĆō2013 to 11.3% (95% CI, 6.3ŌĆō16.6%) [9]. Compared with other racial/ethnic subgroups, non-Hispanic whites had higher mortality due to NAFLD [9]. NAFLD-related mortality increased continuously in Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites from 2007 to 2016, while mortality remained stable in non-Hispanic blacks [9]. A recent study showed that the attributable risk of NAFLD for all-cause mortality is 7.5% (95% CI, 3.0ŌĆō12.0%), although the attributable risk of diabetes was 38.0% (95% CI, 13.1ŌĆō63.0%) [22]. NAFLD-related mortality is expected to increase by 44% to 1.83 million annual deaths by 2030 in the US [10].

The leading cause of death in individuals with NAFLD is cardiovascular disease (summarized in Table 2), followed by extra-hepatic cancer and then liver-related mortality (summarized in Table 3) [12,15].

NAFLD has been associated with an increased risk for the development of cardiovascular disease compared to those without NAFLD. A recent meta-analysis reported that NAFLD was associated with a moderately increased risk of fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular disease events (pooled HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.31ŌĆō1.61) [23]. This risk markedly increased across the severity of NAFLD, especially the fibrosis stage (pooled HR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.68ŌĆō3.72) [23]. This effect is even more substantial with more advanced liver disease, especially with higher fibrosis stage, suggesting that the severity of NAFLD may independently predict risk for incident cardiovascular disease. Even relative to other causes of liver disease, such as viral hepatitis or ALD, the underlying cause of death in individuals with NAFLD is more likely to be cardiovascular disease. Though the independent association between NAFLD and increased cardiovascular mortality may be inconclusive, the underlying cause of death in individuals with NAFLD was more likely to be cardiovascular disease compared with other chronic liver diseases [9]. According to a study from the US national mortality data, the proportion of deaths due to cardiovascular disease in individuals with NAFLD was 16.2%, notably higher than that seen for those with HCV infection (10.3%), hepatitis B virus infection (7.2%), and ALD (5.0%) [7]. This is likely due to the fact that many of the comorbid metabolic abnormalities associated with NAFLD confer an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality. In particular, the accumulation of ectopic fat and resulting pro-inflammatory milieu work synergistically with associated dyslipidemia to accelerate the process of atherosclerosis. Among individuals with NAFLD, a high probability of advanced fibrosis by noninvasive markers was significantly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR: 3.46, 95% CI: 1.91ŌĆō6.25 for NAFLD fibrosis score; HR: 2.68, 95% CI: 1.44ŌĆō4.99 for fibrosis-4 [FIB-4]; HR: 2.53, 95% CI: 1.33ŌĆō4.83 for aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index) [12]. A multi-national study with 458 biopsy-proven NAFLD with bridging fibrosis (n=159) or compensated cirrhosis (n=222) showed that NAFLD with bridging fibrosis had extra-hepatic cancers and cardiovascular events predominantly, while NASH cirrhosis had liver-related events predominantly [24]. Although all-cause mortality was significantly lower in NAFLD with bridging fibrosis, 50% of deaths were directly attributed to extrahepatic cancers or cardiovascular events. In contrast, patients with compensated cirrhosis were at significantly lower risk for non-liver-related deaths (12%) [24]. Therefore, it is essential to identify advanced fibrosis at increased risk of cardiovascular mortality among individuals with NAFLD.

A Korean cohort study reported the association between NAFLD and incident cancer. During the follow-up of the median of 7.5 years, the cancer incidence rate in NAFLD was higher than that of non-NAFLD (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.17ŌĆō1.49) [25]. NAFLD was strongly associated with two extra-hepatic cancers: colorectal cancer in men (HR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.10ŌĆō3.68) and breast cancer in women (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.15ŌĆō3.20) [25]. A high probability of advanced fibrosis was associated with developing all cancers and HCC [25]. A US cohort study with age and sex-matched individuals with and without NAFLD reported that NAFLD was associated with a 90% increased risk of cancer [26]. The incidence of uterine, stomach, pancreas, and colon cancer was higher in those with NAFLD than those without [26]. Other cancers that have been demonstrated to have a higher incidence in those with NAFLD include male genital, female breast, and skin cancer in any gender [27]. Interestingly, NAFLD carries an independent association with an increased risk for cancer, while obesity alone does not [26]. NAFLD is associated with an increased risk for cancer-related mortality even outside the liver, and mortality due to extra-hepatic cancer is rising faster than any other cause of death in individuals with NAFLD at an annual percent change of 15.1% (95% CI, 13.0ŌĆō17.2%) [11]. A recent meta-analysis reported that NAFLD was significantly associated with a 1.5ŌĆō2 fold higher risk of incident gastrointestinal cancers (esophagus, stomach, colorectal, or pancreas) independent of age, sex, obesity, diabetes, smoking, or other potential confounders [28]. In addition, NAFLD was associated with a nearly 1.2ŌĆō1.5-fold higher risk of incident lung, breast, urinary tract, or gynecological cancers [28]. Extra-hepatic cancer and cardiovascular mortality rates in NAFLD-related cirrhosis were more pronounced than in NAFLD without cirrhosis [11]. Though the mechanism of hepatic fibrosis facilitating carcinogenesis in the liver is well-described, how NAFLD and metabolic syndrome are associated with the development of extra-hepatic cancer is less well-understood. It is theorized that hepatic fat deposition results in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to extra-hepatic tissue damage, remodeling, and immune cell dysfunction [29]. This theory partly explains why obesity in the absence of hepatic steatosis is not associated with an increased risk of cancer. However, future mechanistic studies are warranted.

Individuals with NAFLD are at risk for progression to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. This is especially true of the inflammatory subtype of NASH, which carries a 20% lifetime risk of progression to cirrhosis [30]. Prevalence of NAFLD-associated advanced fibrosis in the US has increased markedly in recent years, doubling from 3% in 2005ŌĆō2006 to 6% in 2013ŌĆō2016 [7]. Increased age, insulin resistance, and genetic polymorphisms may be associated with an increased risk for the development of fibrosis in individuals with NAFLD [31]. Liver fibrosis is one of the most important predictors of mortality in NAFLD, and liver-related mortality increases exponentially with the increasing fibrosis stage [32]. A recent meta-analysis showed that individuals with NAFLD and fibrosis were at an increased unadjusted RR of liver-related mortality and all-event liver morbidity compared with those with NAFLD and no fibrosis, and this risk was incremental according to the fibrosis stage [21]. Liver-related mortality included deaths due to compensated cirrhosis, complications of decompensated cirrhosis (ascites or bleeding esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy), acute on chronic liver failure, and/or HCC. A recent US national study showed that liver-related mortality among individuals with NAFLD was responsible for 58.9% of deaths in 2017, although liver-related mortality among those with NAFLD was lower than among those with other chronic liver diseases [11]. NAFLD-related liver mortality markedly increased in recent years with an annual percentage change of 4.9% (95% CI, 4.2ŌĆō5.5%) during the recent decade [9].

In terms of cirrhosis-related mortality, there was an initial increase in cirrhosis due to HCV infection at a rate of 2.9% per year (95% CI, 2.3ŌĆō3.5%) in 2007ŌĆō2014, followed by a decrease in 2014ŌĆō2016 at an annual rate of 6.5% (95% CI, ŌĆō10.3% to ŌĆō2.6%) after the introduction of direct-acting antiviral agents [33]. In contrast, mortality due to NASH cirrhosis increased with an average annual rate of 15.4% (95% CI, 14.1ŌĆō16.7%) during the recent decade [33].

NAFLD is the fastest-growing cause of HCC in the world [34]. HCC risk associated with diabetes seemed to be highest in NAFLD, followed by ALD [35]. Based on dynamic modeling after accounting for current trends in diabetes and obesity, the annual incidence of NAFLD-associated HCC is projected to increase by 137%, from 5,160 cases in 2015 to 12,240 cases in 2030 [10]. A meta-analysis showed that the annual incidence of HCC was 0.44 per 1,000 person-years in those with NAFLD, and even higher in those with biopsy-proven NASH (5.29 per 1,000 person-years) [36]. In addition, HCC is an increasingly-recognized contributor to mortality in individuals with NAFLD, as metabolic syndrome and NAFLD cause almost 10% of cases of HCC in the world and 14.1% of cases of HCC in the US [37]. HCC usually arises in the background of cirrhosis, thought to be related to increased cell turnover from chronic inflammation leading to the formation of driver gene mutations. However, NAFLD and NASH are among the most common causes of HCC in the absence of cirrhosis [38]. HCC is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortalities globally, accounting for 810,000 mortalities in 2015 [39]. Globally, deaths from HCC increased by 60% from 1990 to 2013 [40], and HCC remained the second leading cause of years of life lost due to cancer from 2005 to 2015 [39]. In addition, HCC is a growing burden in individuals with NAFLD. A recent study based on the US National Vital Statistics System demonstrated an increase in the annual rate of HCV infection-related HCC mortality of 5.4% (95% CI, 3.6ŌĆō7.4%) was noted from 2009 to 2014, followed by a decrease from 2014 to 2018 at a rate of 3.5% per year (95% CI, ŌĆō5.9% to ŌĆō1.1%) after the introduction of potent direct-acting antiviral agents [41]. In contrast, age-standardized mortality for HCC from NAFLD demonstrated a linear increase with an annual percentage change of 21.1% (95% CI, 16.9ŌĆō25.4%) from 2009 to 2018 [41].

Type 2 diabetes is common among individuals with NAFLD and NASH, with a global estimated prevalence of 22.5% (95% CI, 17.9ŌĆō27.9%) and 43.6% (30.3ŌĆō58.0%), respectively [36], compared to a contemporary US national prevalence of 14.3% (95% CI, 12.9ŌĆō15.8%) [42]. This strong association reflects the overlapping pathogenesis of metabolic dysregulation shared between the two conditions. However, the relationship between type 2 diabetes and NAFLD is complex and may be bi-directional [43]. The global prevalence of NAFLD and NASH among individuals with type 2 diabetes was 55.5% (95% CI, 47.3ŌĆō63.7%) and 37.3% (95% CI, 24.7ŌĆō50.0%) [44]. A recent US population-based study showed that the prevalence of NAFLD by transient elastography was high in individuals with prediabetes (38.5ŌĆō52.9%) and diabetes (70.7ŌĆō82.1%) [45]. Significant fibrosis and cirrhosis were observed in about one-fourth of individuals with NAFLD and diabetes and one-sixth with NAFLD and prediabetes [45]. In the US general population, age-standardized mortality due to diabetes declined from 112.2 per 100,000 individuals in 2007 to 104.3 in 2017, with the decline of annual percentage change of ŌĆō1.4% (95% CI, ŌĆō1.9% to ŌĆō1.0%) in 2007ŌĆō2014 and stabilization of annual rate of 1.1% (95% CI, ŌĆō0.6% to 2.8%) in 2014ŌĆō2017 [46]. When looking specifically at individuals with NAFLD and diabetes, however, mortality in individuals with NAFLD increased at an annual rate of 11.6% (95% CI, 9.5ŌĆō13.8%) during the same period [47]. Therefore, clinicians bear in mind the harmful impact of NAFLD among individuals with diabetes and vice versa.

As commented above, it is essential to identify and phenotype high-risk profiles at increased risk of all-cause mortality among individuals with NAFLD.

Outcomes of individuals with NAFLD are impacted by several associated factors, including genetic mutations such as polymorphisms in the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3) gene. PNPLA3 encodes an enzyme involved in the hydrolysis of triglycerides, and mutations affecting its function have been associated with increased risk for the development of NAFLD, NASH, advanced fibrosis, and HCC [48]. PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism is more common among Hispanics, contributing to a higher incidence of advanced fibrosis and poorer outcomes from NAFLD compared with any other race/ethnicity [49]. PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism is associated with an earlier age of NAFLD, observation most pronounced in Hispanic Americans [50]. Earlier studies on the association between PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism and all-cause mortality have reported inconsistent results [51,52]. A US population-based study determined that individuals with NAFLD who are homozygous for the PNPLA3 I148M mutation are at increased risk of all-cause mortality as well as liver-related mortality when compared to those with NAFLD and wildtype PNPLA3 genotype during a follow up of 20 years [53,54]. Risk for cardiovascular mortality does not appear to be increased in individuals with PNPLA3 I148M polymorphism. A Chinese study with a mean age of 64 years showed that being homozygous for the PNPLA3 I148M mutation was independently associated with increased liver-related mortality (HR, 3.34; 95% CI, 1.01ŌĆō11.17) but not associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality during 5.3 years follow-up [55]. Further studies are warranted to confirm these associations.

Low thyroid function, defined as higher levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level within the normal reference range of thyroid hormone (ŌĆ£low-normalŌĆØ thyroid function and subclinical hypothyroidism), may cause adverse health effects similar to overt hypothyroidism. Hypothyroidism and low thyroid function are closely associated with increased risk for NAFLD, and a more advanced spectrum of NAFLD, including NASH, and significant fibrosis independent of clinical and metabolic risk factors [56-58]. A recent longitudinal study showed that increasing TSH levels during a median follow-up of 4 years were associated with incident NAFLD independent of other metabolic factors [59]. An US population-based study determined a strong association between NAFLD with increasing plasma TSH levels and all-cause mortality, mainly from cardiovascular mortality [60]. During the median follow-up of 23 years, low thyroid function was independently associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality in individuals with NAFLD (HR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.02ŌĆō1.50), while this association was absent in those without NAFLD [60]. ŌĆ£Low-normalŌĆØ thyroid function and subclinical hypothyroidism were significantly associated with an increase in the risk for all-cause mortality among individuals with NAFLD of 18% and 38%, respectively [60]. Low thyroid function was associated with cardiovascular mortality in individuals with NAFLD (HR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.11ŌĆō2.34). ŌĆ£Low-normalŌĆØ thyroid function and subclinical hypothyroidism were significantly associated with a increase in the risk for cardiovascular mortality among individuals with NAFLD of 50% and 94%, respectively [60].

NAFLD and sarcopenia, which share various pathophysiologic mechanisms, have become increasingly prevalent conditions, resulting in a significant health burden [61]. Previous Asian studies determined sarcopenia is independently associated with NAFLD [62,63] and NAFLD-associated fibrosis [64]. A US population-based study showed an independent association between sarcopenia and NAFLD across various ethnicities [65]. During a median follow-up of 23 years, individuals with both NAFLD and sarcopenia had an increased risk for all-cause mortality (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.06ŌĆō1.55) compared with those without NAFLD and sarcopenia [66]. Sarcopenia was associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality only in individuals with NAFLD after adjusting for advanced fibrosis, whereas this association was absent in those without NAFLD [66]. Other research is consistent with this finding [67,68]. Both NAFLD and sarcopenia confer increased risk for adverse outcomes mediated by a combination of additive and synergic risk factors for all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality [61].

Lifestyle modification is the staple of the management of NAFLD of any severity. Guidelines from both the American Gastroenterological Association and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases on the management of NAFLD recommend lifestyle modification with a combination of physical activity (PA) and dietary modifications to achieve a weight loss of Ōēź5% of total body weight for NAFLD reduction, Ōēź7% for NASH resolution, and Ōēź10% for fibrosis regression/stability [69,70]. Though achieving weight loss is the most important predictor of improvement in NASH or fibrosis, adherence to a high-quality diet and sufficient PA have each been associated with improvement in NAFLD, even in the absence of weight loss [71,72]. Dietary modification includes restriction of caloric intake by 500ŌĆō1,000 kcal as well as prioritization of foods low in carbohydrates and saturated fats, such as in the Mediterranean diet [69,70]. Higher diet quality was associated with significantly lower odds of NAFLD and a lower risk for all-cause mortality [3]. Clinicians focusing on primary prevention with high diet quality may be the ideal way to help curb the rising prevalence of NAFLD.

Practice guidelines recommend that individuals with NAFLD should achieve more than 150 minutes/week of moderate-intensity or more than 75 minutes/week of vigorous-intensity PA [70], which mirrors guideline recommendations for PA in the general population for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease [73]. Although the prevalence of meeting the PA guidelines for leisure time increased in individuals without NAFLD from 2007 through 2016, the trends in meeting PA guidelines for any type of PA remained stable among those with NAFLD, with downtrends in transportation-related PA in the US [74]. Increasing PA beyond the amount recommended by PA guidelines may have an additional benefit to the management for NAFLD [74,75]. While 150ŌĆō299 minutes/week of PA was associated with 40% lower odds of NAFLD, that risk reduction was 49% in those who achieved Ōēź300 minutes/week [75]. PA Ōēź300 minutes/week was also associated with 59% lower odds of fibrosis and 63% lower odds of cirrhosis [75]. Similar to diet quality, the level of PA has also been demonstrated to influence mortality. A recent US population cohort study with an average follow-up of 10.6 years showed that increasing duration of objectively-measured PA was associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality (P for trend <0.001) among individuals with NAFLD [76]. Furthermore, longer total PA was associated with a lower risk for cardiovascular mortality in individuals with NAFLD (P for trend=0.007) [76]. In summary, increasing PA has beneficial survival impacts on all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in individuals with NAFLD. Increasing PA in individuals with NAFLD should be recommended for its benefits on survival.

NAFLD is a highly prevalent and growing problem in the United States and worldwide. The overall incidence of the disease, as well as associated mortality rates, are continually increasing. While NAFLD per se may do not independently increase the risk for all-cause mortality, more severe NAFLD is associated with the underlying metabolic complications responsible for the increased risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortalities. The most common causes of death in individuals with NAFLD are cardiovascular disease, extra-hepatic cancer, liver disease (including decompensated cirrhosis and HCC), and diabetes. Mortality in NAFLD is further influenced by mutations in the PNPLA3 gene, low thyroid function, and sarcopenia. Weight loss through diet and PA is the recommended approach for NAFLD. Both diet and exercise have each been demonstrated to have significant effects on mortality, including all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. As the health burden of NAFLD increases, future studies may demonstrate an association between NAFLD and mortality, especially as more long-term mortality data is available that captures the downstream cardiovascular consequences of long-standing NAFLD and fibrosis.

FOOTNOTES

AuthorsŌĆÖ contribution

Dr. Peter Konyn was involved in the study concept and design, acquisition of data, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Dr. Aijaz Ahmed and Dr. Donghee Kim were involved in the study concept and design, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, and study supervision.

Figure┬Ā1.

Causes and risk profiles of mortality among individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; PNPLA3, patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3.

Table┬Ā1.

Essential studies evaluating all-cause mortality in individuals with NAFLD

| Study | Country | Total population (number of NAFLD) | Diagnostic method | Average follow-up (years) | Outcomes | Confounder adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dam-Larsen et al. [19] (2004) | Denmark | 215 | Fatty liver: liver biopsy | NAFLD: 16.7 | Overall estimated survival in NAFLD was not different from general Danish population | None |

| Alcoholic fatty liver: 9.2 | ||||||

| Adams et al. [15] (2005) | USA | 420 NAFLD | NAFLD: ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, liver biopsy, or cryptogenic cirrhosis + metabolic syndrome | 7.6 | Overall survival in NAFLD was lower than the expected survival for the general population (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.003ŌĆō1.76) | Age and sex |

| Kim et al. [12] (2013) | USA | 11,154 (NAFLD: 34%) | NAFLD: ultrasonography | 14.5 | NAFLD had no association with all-cause mortality (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.78ŌĆō1.02). | Age, sex, race or ethnicity, education, income, diabetes, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, lipid-lowering medication, smoking status, waist circumference, alcohol consumption, caffeine consumption, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, transferrin saturation, and C-reactive protein |

| Fibrosis: non-invasive panels | Advanced fibrosis had a 69% increase in all-cause mortality (HR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.09ŌĆō2.63) | |||||

| Estes et al. [10] (2018) | USA | N/A | N/A | N/A | Total annual deaths in NAFLD patients were projected to reach 1.83 million in 2030, a 44% increase from a baseline of 1.27 million in 2015 | N/A |

| Kim et al. [9] (2018) | USA | 25,379,768 (NAFLD: 30,091) | NAFLD: ICD-10 codes | 10 | Between 2007 and 2016, there was a linear increase in age-standardized all-cause mortality for NAFLD (APC, 7.8; 95% CI, 6.3ŌĆō9.4). NAFLD-related mortality increased continuously in Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites from 2007 to 2016, while mortality remained stable in non-Hispanic black | Age |

| Taylor et al. [21] (2020) | Multinational | 4,428 NAFLD | NAFLD: liver biopsy | 6.2 | Biopsy-confirmed fibrosis was associated with increased all-cause mortality in NAFLD, which increased incrementally with increasing fibrosis stage. | Variable |

| Fibrosis: liver biopsy | Stage 1: HR 1.12 (95% CI, 0.91ŌĆō1.38) | |||||

| Stage 2: HR 1.50 (95% CI, 1.20ŌĆō1.86) | ||||||

| Stage 3: HR 2.13 (95% CI, 1.70ŌĆō2.67) | ||||||

| Stage 4: HR 3.42 (95% CI, 2.63ŌĆō4.46) | ||||||

| Alvarez et al. [22] (2020) | USA | 12,253 NAFLD | NAFLD: ultrasonography | 23.3 | The population attributable fraction for overall mortality associated with NAFLD was 7.5% (95% CI, 2.1ŌĆō79.6) | Age, sex, race/ethnicity, years of education, physical activity score, cigarette smoking, moderate alcohol consumption, body mass index |

| Kim et al. [13] (2021) | USA | 7,761 (NAFLD: 29.5% MAFLD: 25.9%) | NAFLD: ultrasonography | 23 | MAFLD(ŌĆō)/NAFLD(+) had no association with all-cause mortality (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.60ŌĆō1.46). | Age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, smoking status, alanine aminotransferase, sedentary lifestyle, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, fasting triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, waist circumference, and C-reactive protein |

| MAFLD: criteria proposed by international panel | MAFLD(+)/NAFLD(ŌĆō) (HR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.19ŌĆō2.32) and MAFLD(+)/NAFLD(+) (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.00ŌĆō1.26) were both associated with an increase in all-cause mortality | |||||

| Simon et al. [20] (2021) | Sweden | 10,568 NAFLD | NAFLD: liver biopsy | 14.2 | NAFLD at all histological stages was associated with increased all-cause mortality when compared to the general population (HR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.64ŌĆō1.79). | Age at the index date, sex, county, calendar year, education level, cardiovascular disease, and the metabolic syndrome, defined as a composite categorical variable (ranging from 0 to 4) with 1 point given for each of the following conditions (i.e., diabetes, obesity, hypertension and/or dyslipidemia) |

| Fibrosis: liver biopsy | Overall mortality increased with the worsening stage of fibrosis. | |||||

| Simple steatosis: HR 1.71 (95% CI, 1.64ŌĆō1.79) | ||||||

| NASH without fibrosis: HR 2.14 (95% CI, 1.93ŌĆō2.38) | ||||||

| Non-cirrhotic fibrosis: HR 2.44 (95% CI, 2.22ŌĆō2.69) | ||||||

| Cirrhosis: HR 3.79 (95% CI, 3.34ŌĆō4.30) | ||||||

| P trend: <0.01 |

Table┬Ā2.

Essential studies evaluating cardiovascular mortality in individuals with NAFLD

| Study | Country | Total population (number of NAFLD) | Diagnostic method | Average follow-up (years) | Outcomes | Confounder adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams et al. [15] (2005) | USA | 420 NAFLD | NAFLD: ultrasonography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, liver biopsy, or cryptogenic cirrhosis + metabolic syndrome | 7.6 | Cardiovascular disease was identified as the cause of death in 28% of participants. | Age and sex |

| Kim et al. [12] (2013) | USA | 11,154 (NAFLD: 34%) | NAFLD: ultrasonography Fibrosis: non-invasive panels | 14.5 | Increased mortality in individuals with NAFLD and hepatic fibrosis was driven mostly by cardiovascular death. | Age, sex, race or ethnicity, education, income, diabetes, hypertension, history of cardiovascular disease, lipid-lowering medication, smoking status, waist circumference, alcohol consumption, caffeine consumption, total cholesterol, high- density lipoprotein cholesterol, transferrin saturation, and C-reactive protein |

| NFS: HR 3.56 (95% CI, 1.91ŌĆō6.25) | ||||||

| APRI: HR 2.53 (95% CI, 1.33ŌĆō4.83) | ||||||

| FIB-4: HR 2.68 (95% CI, 1.44ŌĆō4.99) | ||||||

| Vilar-Gomez et al. [24] (2018) | Multinational | 458 NAFLD (Bridging fibrosis: 35%, Compensated cirrhosis: 65%) | NAFLD, fibrosis, or cirrhosis: liver biopsy | 5.5 | Cardiovascular deaths made up a higher proportion of overall mortality in patients with NAFLD and bridging fibrosis (5%) than in cirrhosis (1ŌĆō2%). | Center, race/ethnicity, age, sex, calendar year of patientsŌĆÖ recruitment, baseline body mass index, hypertension, history of previous vascular events or malignant neoplasm, anti-diabetic, antihypertensive, and hypolipidemic drugs, aspirin, current smoking and diagnosis of type 2 diabetes as timevarying covariates. |

| Annualized incidence of major vascular events in the entire cohort was 0.9 (95% CI, 0.5ŌĆō1.8). | ||||||

| Kim et al. [9] (2018) | USA | 25,379,768 (NAFLD: 30,091) | NAFLD: ICD-10 codes | 10 | Cardiovascular disease made up a higher proportion of overall mortality in individuals with NAFLD than those with other chronic liver diseases. | Age |

| NAFLD-related cardiovascular mortality steadily decreased over the period. | ||||||

| Kim et al. [11] (2019) | USA | 27,903,198 (NAFLD: 33,945) | NAFLD: ICD-10 codes | 11 | The cause of death in NAFLD was more likely to be cardiovascular disease (approximately 20%), which increased at a gradual rate (APC, 2.0%; 95% CI, 0.6ŌĆō3.4), whereas liver-related mortality increased rapidly (APC, 12.6%; 95% CI, 11.7ŌĆō13.5). | Age |

| Mantovani et al. [23] (2021) | Multinational | 5,802,226 | NAFLD: liver biopsy, imaging techniques, or ICD-10 codes in the absence of significant alcohol consumption | 6.5 | Incidence of fatal or non-fatal cardiovascular events was higher in individuals with NALFD (HR: 1.45; 95% CI, 1.31ŌĆō1.61). | Age, sex, adiposity measures, diabetes, and other common cardiometabolic risk factors |

| Incidence increased with increasing severity of fibrosis (pooled randomeffects HR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.68ŌĆō3.72). |

Table┬Ā3.

Essential studies evaluating liver-related mortality in individuals with NAFLD

| Study | Country | Total population (number of NAFLD) | Diagnostic method | Average follow-up (years) | Outcomes | Confounder adjustment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Younossi et al. [37] (2015) | USA | 19,916 (NAFLD: 1,944) | NAFLD: ICD-9 codes | 10 | 14.1% of HCC cases were related to NAFLD. | Age, gender, cancer stage, residence region, education, median household income, modified Charlson comorbidity index, and date of diagnosis |

| The proportion of HCC related to NAFLD had a 9% average annual increase between 2004ŌĆō2009. | ||||||

| NAFLD-related HCC was associated with increased risk of 1-year overall mortality (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.01ŌĆō1.45) | ||||||

| Dulai et al. [32] (2017) | Multinational | 1,395 NAFLD | NAFLD: liver biopsy | 11.7 | Individuals with NAFLD and stage 2 fibrosis or higher had increased risk for liver-related mor tality when compared to individuals with NAFLD and stage 0 fibrosis (MRR, 9.57; 95% CI, 0.17-11.95) | None |

| Liver-related mortality rates increased exponentially with increasing stage of fibrosis. Liver-related deaths made up 59% of all-cause mortality in individuals with stage 4 fibrosis. | ||||||

| Kim et al. [33] (2019) | USA | 25,379,768 (NAFLD: 12,099) | NAFLD: ICD-10 codes | 10 | Age-standardized cirrhosis-related mortality rates in individuals with NAFLD increased linearly from 2007 and 2016 with an average annual percent change of 15.4% (95% CI, 14.1ŌĆō16.7). | Age |

| Age-standardized HCC-related mortality rates in individuals with NAFLD increased linearly from 2007 and 2016 with an average annual percent change of 19.1% (95% CI, 14.0ŌĆō24.5). | ||||||

| Taylor et al. [21] (2020) | Multinational | 4,428 NAFLD | NAFLD: liver biopsy | 6.2 | Biopsy-confirmed fibrosis was associated with increased liver-related mortality in NAFLD. This increased incrementally with increasing fibrosis stage, reaching significance at stage 3 fibrosis. | Variable |

| Fibrosis: liver biopsy | Stage 1: HR 1.05 (95% CI, 0.35ŌĆō3.16) | |||||

| Stage 2: HR 2.53 (95% CI, 0.88ŌĆō7.27) | ||||||

| Stage 3: HR 6.65 (95% CI, 1.99ŌĆō22.25) | ||||||

| Stage 4: HR 11.13 (95% CI, 4.15ŌĆō29.84) | ||||||

| Kim et al. [41] (2020) | USA | 25,907,886 (NAFLD: 15,812) | NAFLD: ICD-10 codes | 10 | Age-standardized cirrhosis-related mortality rate in individuals with NAFLD increased linearly with an average annual percent change of 16.2% (95% CI, 15.4ŌĆō17.0) between 2009ŌĆō2018. | Age |

| Age-standardized HCC-related mortality rate in individuals with NAFLD increased linearly with an average annual percent change of 21.1% (95% CI, 16.9ŌĆō25.4) between 2009ŌĆō2018. |

Abbreviations

ALD

alcohol-related liver disease

CI

confidence interval

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

HCV

hepatitis C virus

HR

hazard ratio

NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

RR

relative risk

PA

physical activity

PNPLA3

patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3

TSH

thyroid-stimulating hormone

REFERENCES

1. Murag S, Ahmed A, Kim D. Recent epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut Liver 2021;15:206-216.

2. Kang SH, Lee HW, Yoo JJ, Cho Y, Kim SU, Lee TH, et al. KASL clinical practice guidelines: management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol 2021;27:363-401.

3. Yoo ER, Kim D, Vazquez-Montesino LM, Escober JA, Li AA, Tighe SP, et al. Diet quality and its association with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Liver Int 2020;40:815-824.

4. Li AA, Ahmed A, Kim D. Extrahepatic manifestations of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut Liver 2020;14:168-178.

5. Konyn P, Alshuwaykh O, Dennis BB, Cholankeril G, Ahmed A, Kim D. Gallstone disease and its association with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022 May 26;doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.04.043.

6. Kim D, Cholankeril G, Loomba R, Ahmed A. Prevalence of fatty liver disease and fibrosis detected by transient elastography in adults in the United States, 2017-2018. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:1499-1501 e2.

7. Kim D, Kim W, Adejumo AC, Cholankeril G, Tighe SP, Wong RJ, et al. Race/ethnicity-based temporal changes in prevalence of NAFLD-related advanced fibrosis in the United States, 2005-2016. Hepatol Int 2019;13:205-213.

8. Park SH, Plank LD, Suk KT, Park YE, Lee J, Choi JH, et al. Trends in the prevalence of chronic liver disease in the Korean adult population, 1998-2017. Clin Mol Hepatol 2020;26:209-215.

9. Kim D, Li AA, Gadiparthi C, Khan MA, Cholankeril G, Glenn JS, et al. Changing trends in etiology-based annual mortality from chronic liver disease, from 2007 through 2016. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1154-1163 e3.

10. Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology 2018;67:123-133.

11. Kim D, Adejumo AC, Yoo ER, Iqbal U, Li AA, Pham EA, et al. Trends in mortality from extrahepatic complications in patients with chronic liver disease, from 2007 through 2017. Gastroenterology 2019;157:1055-1066 e11.

12. Kim D, Kim WR, Kim HJ, Therneau TM. Association between noninvasive fibrosis markers and mortality among adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States. Hepatology 2013;57:1357-1365.

13. Kim D, Konyn P, Sandhu KK, Dennis BB, Cheung AC, Ahmed A. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is associated with increased all-cause mortality in the United States. J Hepatol 2021;75:1284-1291.

14. Ng CH, Huang DQ, Nguyen MH. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease versus metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: prevalence, outcomes and implications of a change in name. Clin Mol Hepatol 2022;28:790-801.

15. Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 2005;129:113-121.

16. Kwak MS, Kim D. Long-term outcomes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr hepat0 rep 2015;14:69-76.

17. Kim D, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in early life and all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2022;11:317-319.

18. Ruhl CE, Everhart JE. Elevated serum alanine aminotransferase and gamma-glutamyltransferase and mortality in the United States population. Gastroenterology 2009;136:477-485 e11.

19. Dam-Larsen S, Franzmann M, Andersen IB, Christoffersen P, Jensen LB, S├Ėrensen TI, et al. Long term prognosis of fatty liver: risk of chronic liver disease and death. Gut 2004;53:750-755.

20. Simon TG, Roelstraete B, Khalili H, Hagstr├Čm H, Ludvigsson JF. Mortality in biopsy-confirmed nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: results from a nationwide cohort. Gut 2021;70:1375-1382.

21. Taylor RS, Taylor RJ, Bayliss S, Hagstr├Čm H, Nasr P, Schattenberg JM, et al. Association between fibrosis stage and outcomes of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2020;158:1611-1625 e12.

22. Alvarez CS, Graubard BI, Thistle JE, Petrick JL, McGlynn KA. Attributable fractions of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease for mortality in the United States: results from the third national health and nutrition examination survey with 27 years of follow-up. Hepatology 2020;72:430-440.

23. Mantovani A, Csermely A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Corey KE, Simon TG, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:903-913.

24. Vilar-Gomez E, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Wai-Sun Wong V, Castellanos M, Aller-de la Fuente R, Metwally M, et al. Fibrosis severity as a determinant of cause-specific mortality in patients with advanced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a multi-national cohort study. Gastroenterology 2018;155:443-457 e17.

25. Kim GA, Lee HC, Choe J, Kim MJ, Lee MJ, Chang HS, et al. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and cancer incidence rate. J Hepatol 2018;68:140-146.

26. Allen AM, Hicks SB, Mara KC, Larson JJ, Therneau TM. The risk of incident extrahepatic cancers is higher in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease than obesity - a longitudinal cohort study. J Hepatol 2019;71:1229-1236.

27. Huber Y, Labenz C, Michel M, W├Črns MA, Galle PR, Kostev K, et al. Tumor incidence in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2020;117:719-724.

28. Mantovani A, Petracca G, Beatrice G, Csermely A, Tilg H, Byrne CD, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and increased risk of incident extrahepatic cancers: a meta-analysis of observational cohort studies. Gut 2022;71:778-788.

29. Gehrke N, Schattenberg JM. Metabolic inflammation-a role for hepatic inflammatory pathways as drivers of comorbidities in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease? Gastroenterology 2020;158:1929-1947 e6.

30. Sheka AC, Adeyi O, Thompson J, Hameed B, Crawford PA, Ikramuddin S. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a review. JAMA 2020;323:1175-1183.

31. Kasper P, Martin A, Lang S, K├╝tting F, Goeser T, Demir M, et al. NAFLD and cardiovascular diseases: a clinical review. Clin Res Cardiol 2021;110:921-937.

32. Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J, Soni M, Prokop LJ, Younossi Z, et al. Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 2017;65:1557-1565.

33. Kim D, Li AA, Perumpail BJ, Gadiparthi C, Kim W, Cholankeril G, et al. Changing trends in etiology-based and ethnicity-based annual mortality rates of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Hepatology 2019;69:1064-1074.

34. Ioannou GN. Epidemiology and risk-stratification of NAFLDassociated HCC. J Hepatol 2021;75:1476-1484.

35. Shin HS, Jun BG, Yi SW. Impact of diabetes, obesity, and dyslipidemia on the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver diseases. Clin Mol Hepatol 2022;28:773-789.

36. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-metaanalytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73-84.

37. Younossi ZM, Otgonsuren M, Henry L, Venkatesan C, Mishra A, Erario M, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the United States from 2004 to 2009. Hepatology 2015;62:1723-1730.

38. Konyn P, Ahmed A, Kim D. Current epidemiology in hepatocellular carcinoma. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;15:1295-1307.

39. Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration, Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:524-548.

40. GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;385:117-171.

41. Kim D, Konyn P, Cholankeril G, Wong RJ, Younossi ZM, Ahmed A, et al. Decline in annual mortality of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States, from 2009 to 2018. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1558-1560 e2.

42. Wang L, Li X, Wang Z, Bancks MP, Carnethon MR, Greenland P, et al. Trends in prevalence of diabetes and control of risk factors in diabetes among US adults, 1999-2018. JAMA 2021;326:1-13.

43. Kim D, Touros A, Kim WR. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome. Clin Liver Dis 2018;22:133-140.

44. Younossi ZM, Golabi P, de Avila L, Paik JM, Srishord M, Fukui N, et al. The global epidemiology of NAFLD and NASH in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol 2019;71:793-801.

45. Kim D, Cholankeril G, Loomba R, Ahmed A. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatic fibrosis among US Adults with prediabetes and diabetes, NHANES 2017-2018. J Gen Intern Med 2022;37:261-263.

46. Kim D, Li AA, Cholankeril G, Kim SH, Ingelsson E, Knowles JW, et al. Trends in overall, cardiovascular and cancer-related mortality among individuals with diabetes reported on death certificates in the United States between 2007 and 2017. Diabetologia 2019;62:1185-1194.

47. Kim D, Cholankeril G, Kim SH, Abbasi F, Knowles JW, Ahmed A. Increasing mortality among patients with diabetes and chronic liver disease from 2007 to 2017. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:992-994.

48. Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Meta-analysis of the influence of I148M variant of patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 gene (PNPLA3) on the susceptibility and histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2011;53:1883-1894.

49. Yoo ER, Ahmed A, Kim D. Genetic factors and continental ancestry account for some disparities in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among hispanic subgroups. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:2176-2178.

50. Walker RW, Belbin GM, Sorokin EP, Van Vleck T, Wojcik GL, Moscati A, et al. A common variant in PNPLA3 is associated with age at diagnosis of NAFLD in patients from a multi-ethnic biobank. J Hepatol 2020;72:1070-1081.

51. Meffert PJ, Repp KD, V├Člzke H, Weiss FU, Homuth G, K├╝hn JP, et al. The PNPLA3 SNP rs738409:G allele is associated with increased liver disease-associated mortality but reduced overall mortality in a population-based cohort. J Hepatol 2018;68:858-860.

52. Simons N, Isaacs A, Koek GH, Ku─Ź S, Schaper NC, Brouwers MCGJ. PNPLA3, TM6SF2, and MBOAT7 genotypes and coronary artery disease. Gastroenterology 2017;152:912-913.

53. Wijarnpreecha K, Scribani M, Raymond P, Harnois DM, Keaveny AP, Ahmed A, et al. PNPLA3 gene polymorphism and overall and cardiovascular mortality in the United States. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;35:1789-1794.

54. Wijarnpreecha K, Scribani M, Raymond P, Harnois DM, Keaveny AP, Ahmed A, et al. PNPLA3 gene polymorphism and liver- and extrahepatic cancer-related mortality in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:1064-1066.

55. Xia M, Ma S, Huang Q, Zeng H, Ge J, Xu W, et al. NAFLD-related gene polymorphisms and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in an Asian population: the Shanghai Changfeng Study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022;55:705-721.

56. Chung GE, Kim D, Kim W, Yim JY, Park MJ, Kim YJ, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease across the spectrum of hypothyroidism. J Hepatol 2012;57:150-156.

57. Kim D, Kim W, Joo SK, Bae JM, Kim JH, Ahmed A. Subclinical hypothyroidism and low-normal thyroid function are associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;16:123-131 e1.

58. Kim D, Yoo ER, Li AA, Fernandes CT, Tighe SP, Cholankeril G, et al. Low-normal thyroid function is associated with advanced fibrosis among adults in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:2379-2381.

59. Chung GE, Kim D, Kwak MS, Yim JY, Ahmed A, Kim JS. Longitudinal change in thyroid-stimulating hormone and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:848-849 e1.

60. Kim D, Vazquez-Montesino LM, Escober JA, Fernandes CT, Cholankeril G, Loomba R, et al. Low thyroid function in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:1496-1504.

61. Kuchay MS, Mart├Łnez-Montoro JI, Kaur P, Fern├Īndez-Garc├Ła JC, Ramos-Molina B. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related fibrosis and sarcopenia: an altered liver-muscle crosstalk leading to increased mortality risk. Ageing Res Rev 2022;80:101696.

62. Hong HC, Hwang SY, Choi HY, Yoo HJ, Seo JA, Kim SG, et al. Relationship between sarcopenia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the Korean Sarcopenic Obesity Study. Hepatology 2014;59:1772-1778.

63. Lee YH, Jung KS, Kim SU, Yoon HJ, Yun YJ, Lee BW, et al. Sarcopaenia is associated with NAFLD independently of obesity and insulin resistance: nationwide surveys (KNHANES 2008-2011). J Hepatol 2015;63:486-493.

64. Koo BK, Kim D, Joo SK, Kim JH, Chang MS, Kim BG, et al. Sarcopenia is an independent risk factor for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and significant fibrosis. J Hepatol 2017;66:123-131.

65. Wijarnpreecha K, Kim D, Raymond P, Scribani M, Ahmed A. Associations between sarcopenia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and advanced fibrosis in the USA. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;31:1121-1128.

66. Kim D, Wijarnpreecha K, Sandhu KK, Cholankeril G, Ahmed A. Sarcopenia in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the United States. Liver Int 2021;41:1832-1840.

67. Moon JH, Koo BK, Kim W. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and sarcopenia additively increase mortality: a Korean nationwide survey. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021;12:964-972.

68. Golabi P, Gerber L, Paik JM, Deshpande R, de Avila L, Younossi ZM. Contribution of sarcopenia and physical inactivity to mortality in people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. JHEP Rep 2020;2:100171.

69. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Charlton M, Cusi K, Rinella M, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 2018;67:328-357.

70. Younossi ZM, Corey KE, Lim JK. AGA clinical practice update on lifestyle modification using diet and exercise to achieve weight loss in the management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: expert review. Gastroenterology 2021;160:912-918.

71. Kistler KD, Brunt EM, Clark JM, Diehl AM, Sallis JF, Schwimmer JB, et al. Physical activity recommendations, exercise intensity, and histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:460-468 quiz 469.

72. Haufe S, Engeli S, Kast P, B├Čhnke J, Utz W, Haas V, et al. Randomized comparison of reduced fat and reduced carbohydrate hypocaloric diets on intrahepatic fat in overweight and obese human subjects. Hepatology 2011;53:1504-1514.

73. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Galuska DA, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018;320:2020-2028.

74. Kim D, Vazquez-Montesino LM, Li AA, Cholankeril G, Ahmed A. Inadequate physical activity and sedentary behavior are independent predictors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2020;72:1556-1568.

-

METRICS

- ORCID iDs

-

Donghee Kim

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1919-6800 - Related articles

-

Recent updates on pharmacologic therapy in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease2024 January;30(1)

Letter regarding ŌĆ£Risk factors in nonalcoholic fatty liver diseaseŌĆØ2023 October;29(4)

The effect of moderate alcohol consumption on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease2023 April;29(2)

Implications of comorbidities in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease2023 April;29(2)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print