| Korean J Hepatol > Volume 17(2); 2011 > Article |

ABSTRACT

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is performed as an alternative to surgical resection for primary or secondary liver malignancies. Although RFA can be performed safely in most patients, early and late complications related to mechanical or thermal damage occur in 8-9.5% cases. Hemocholecyst, which refers to hemorrhage of the gallbladder, has been reported with primary gallbladder disease or as a secondary event associated with hemobilia. Hemobilia, defined as hemorrhage in the biliary tract and most commonly associated with accidental or iatrogenic trauma, is a rare complication of RFA. Here we report a case of hemocholecyst associated with hemobilia after RFA for hepatocellular carcinoma that was successfully managed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary malignant liver tumor. Although surgical resection is the best curative treatment option,1,2 there are several obstacles that limit surgical resection such as tumor number, location, hepatic reserve, and patient performance status.3 Therefore, alternative techniques such as percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), microwave therapy, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) have been practiced for the treatment of HCC.4-6

RFA is an effective loco-regional treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma that was first introduced in 1996.7 As a minimally invasive procedure, RFA is considered as a relatively simple and safe modality for treatment of HCC. However RFA may cause early and late complications related to mechanical and thermal damage. Post-RFA complications such as liver abscess, tumor seeding, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, gastrointestinal perforation, intraperitoneal bleeding, and skin burn have been reported from 5.2% to 9.5% in literature.8-10

Hemobilia is defined as hemorrhage from the biliary tree. Melena and upper abdominal pain are common symptoms of hemobilia. The causes of hemobilia are known as trauma, infection, tumor, inflammation, and gallstones. Hemobilia has been reported as a rare biliary complication after percutaneous hepatic intervention.11 Hemocholecyst secondary to hemobilia is also a rare sequelae of hemobilia.

As we experienced hemobilia accompanied with hemocholecyst after RFA for treatment of HCC, we report clinical course and management of the present case.

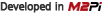

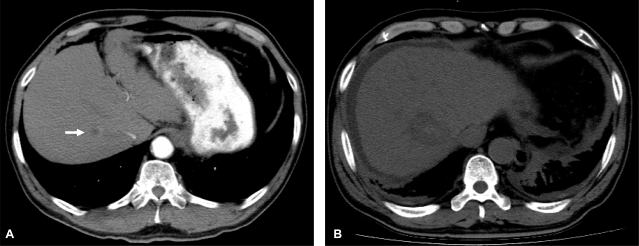

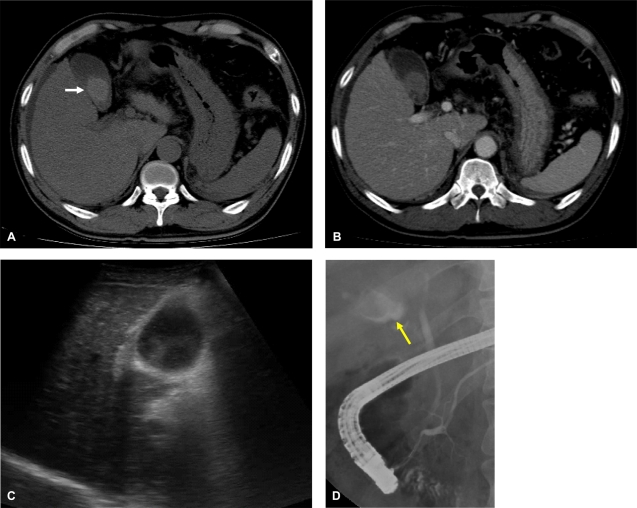

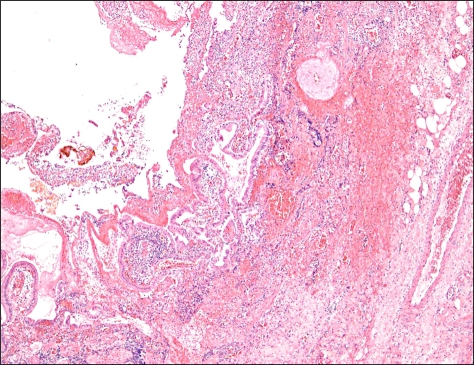

A 69-year-old man visited the emergency room due to right upper quadrant abdominal pain for two days. He had a medical history of hypertension, cerebral infarction, and liver cirrhosis secondary to chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Two weeks ago, the patient was treated with RFA for 14 mm sized HCC in segment 8 (Fig. 1A, B). Physical examination and laboratory findings were within normal range when RFA was performed. Percutaneous RFA was performed under local anesthesia using cool-tip electrode with a 3-cm exposed tip (ACT2030, Valleylab, Boulder, Colorado, U.S.A) according to manufacture's manual. Multiple overlapping ablations were applied for 2 cycles with 12 minutes each cycle. Patient was discharged from hospital 24 hours after RFA without any immediate complication. The patient was doing well after discharge. Ten days after discharge, patient had nausea and right upper abdominal discomfort. The patient felt severe progressive right upper abdominal pain associated with fever. Physical examination showed tenderness at right upper abdomen with positive Murphy's sign. Laboratory finding showed increased serum levels of alanine transaminase (242 IU/L from 24 IU/L), total bilirubin (3.6 mg/dL from 0.4 mg/dL), and decreased hemoglobin level (12.1 g/dL from 15.1 g/dL). Acute infection was suggested by leukocyte count (20,180/mm3), C-reactive protein (14.2 mg/dL). Abdominal computed tomogram (CT) showed gallbladder (GB) filled with high density material, considered as hematoma (Fig. 2A, B). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed heterogenous echogenic mass in GB (Fig. 2C). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed an irregular shaped filling defect in GB with normal cholangiogram (Fig. 2D). Abdominal pain gradually decreased with antibiotic therapy after endoscopic sphincterectomy to decompress the bile duct. The follow up CT scan three days after ERCP showed a decreased but remnant mass-like lesion within GB (Fig. 3). Due to persistent pain, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed. There were blood clots in GB wall and shows no source of bleeding. The pathologic examination showed hemorrhage and diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells at GB wall without primary GB pathology (Fig. 4). After cholecystectomy, Patient's symptom subsided and laboratory finding improved. The patient was discharged five days after cholecystectomy without any complication.

Hemobilia involving the GB can present with signs and symptoms of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and eventually lead to GB rupture and hemoperitoneum, when cystic duct is obstructed by blood clots.12,13 The mechanism of hemobilia after RFA is mainly due to direct traumatic injury to biliary and vascular structures during electrode advancement and thermal injury may also contribute to bile duct and vascular damage.14 Hemobilia related to RFA has been reported ranging from 0.02% to 0.25%.12-14

The term "hemocholecyst", introduced in 1961, refers to describe hemorrhage of GB. Originally, this term applies only to atraumatic bleeding confined to the GB.15,16 However, it might be very difficult to differentiate hemocholecyst from hemobilia in clinical practice. Hemocholecyst can cause hemobilia, or vice versa, hemobilia may result in hemocholecyst.17,18 Causes of primary hemocholecyst are limited including GB cancer, cholelithiasis, vascular disorders, and the presence of heterotopic gastrointestinal mucosa within the GB. Secondary hemocholecyst can be resulted from iatrogenic trauma, such as liver biopsy and RFA.12,13,16 The diagnosis of hemocholecyst is difficult. The sonographic appearance of blood clots within the GB appears as clumps of echogenic material. CT scan can show high density mass-like lesion in distended GB and high density mass.19 ERCP can identify evidence of bleeding at duodenal ampullar in only 30% of patients. In the present case, we identified high attenuating mass like lesion in GB through sonography and abdominal CT scan, which showed hematoma density about 60 Hounsfield number in CT scan. ERCP failed to show evidence of bleeding in biliary system in present case, which is mainly due to time delay of 2 weeks between ERCP and RFA. Direct GB injury from RFA might be an another etiology of hemocholecyst, but, considering the fact that the ablation site is not close from the GB, We presumed that hemocholecyst is associated with hemobilia after RFA. Although definite hemobilia could not be identified, no histologic evidence of primary GB disease causing hemorrhage made it diagnosed as hemocholecyst associated with hemobilia

It is difficult to provide an algorithm for management of hemocholecyst associated with hemobilia. There are various treatment options proposed. Once the clot in the GB begins to organize, it is very unlikely to dissolve. Therefore in most cases, open or laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be performed.20 Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed in present case due to persistent pain and the patient successfully recovered.

We assume the thermal injury during RFA caused hemobilia subacutely which eventually resulted in hemocholecyst. We diagnosed the hemocholecyst by abdominal ultrasound and CT scan. We performed ERCP to decompress biliary tract by endoscopic sphincterotomy. Eventually the patient was successfully managed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

In conclusion, although hemocholecyst associated with hemobilia is a very rare complication of RFA, we should suspect possibility of this complication in patients presenting with continued abdominal pain and decrease in hemoglobin level without obvious cause. Early recognition and management is crucial not to miss the chance for the opportune treatment. Prompt surgical management should be considered when medical therapy fails to improve clinical course.

Abbreviations

AFP

alpha fetoprotein

CT

computed tomography

ERCP

endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography

GB

gallbladder

HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

PEI

percutaneous ethanol injection

PIVKA-II

protein induced by vitamin K antagonist-II

RFA

radiofrequency ablation

TACE

transcatheter arterial chemoembolization

REFERENCES

1. Shimozawa N, Hanazaki K. Longterm prognosis after hepatic resection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 2004;198:356-365. 14992736.

2. Zhou L, Rui JA, Wang SB, Chen SG, Qu Q, Chi TY, et al. Outcomes and prognostic factors of cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after radical major hepatectomy. World J Surg 2007;31:1782-1787. 17610113.

3. McGhana JP, Dodd GD 3rd. Radiofrequency ablation of the liver: current status. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:3-16. 11133529.

4. Crocetti L, Lencioni R. Thermal ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Imaging 2008;8:19-26. 18331969.

5. Mazzanti R, Arena U, Pantaleo P, Antonuzzo L, Cipriani G, Neri B, et al. Survival and prognostic factors in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma treated by percutaneous ethanol injection: a 10-year experience. Can J Gastroenterol 2004;18:611-618. 15497001.

6. Vogl TJ, Zangos S, Balzer JO, Nabil M, Rao P, Eichler K, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in hepatocellular carcinoma: technique, indication and results. Rofo 2007;179:1113-1126. 17948190.

7. McGahan JP, Gu WZ, Brock JM, Tesluk H, Jones CD. Hepatic ablation using bipolar radiofrequency electrocautery. Acad Radiol 1996;3:418-422. 8796695.

8. Curley SA, Marra P, Beaty K, Ellis LM, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, et al. Early and late complications after radiofrequency ablation of malignant liver tumors in 608 patients. Ann Surg 2004;239:450-458. 15024305.

9. Chen TM, Huang PT, Lin LF, Tung JN. Major complications of ultrasound-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablations for liver malignancies: single center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:e445-e450. 17683478.

10. Zavaglia C, Corso R, Rampoldi A, Vinci M, Belli LS, Vangeli M, et al. Is percutaneous radiofrequency thermal ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma a safe procedure? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;20:196-201. 18301300.

11. Bloechle C, Izbicki JR, Rashed MY, el-Sefi T, Hosch SB, Knoefel WT, et al. Hemobilia: presentation, diagnosis, and management. Am J Gastroenterol 1994;89:1537-1540. 8079933.

12. Heise CP, Giswold M, Eckhoff D, Reichelderfer M. Cholecystitis caused by hemocholecyst from underlying malignancy. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:805-808. 10710081.

13. Yamamoto T, Kubo S, Hirohashi K, Tanaka S, Uenishi T, Ogawa M, et al. Secondary hemocholecyst after radiofrequency ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol 2003;38:399-403. 12743783.

14. Rhim H, Lim HK, Kim YS, Choi D, Lee KT. Hemobilia after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Imaging 2006 12 15;[Epub ahead of print].

16. Fitzpatrick TJ. Hemocholecyst: a neglected cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Ann Intern Med 1961;55:1008-1013. 13893372.

17. Counihan TC, Islam S, Swanson RS. Acute cholecystitis resulting from hemobilia after tru-cut biopsy: a case report and brief review of the literature. Am Surg 1996;62:757-758. 8751769.

18. Lee SL, Caruso DM. Acute cholecystitis secondary to hemobilia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 1999;9:347-349. 10488830.

Figure 1

(A) Computed tomography (CT) scan showing a small enhanced nodule (arrow) in segment 8. (B) The same lesion after radiofrequency ablation (RFA) therapy.

Figure 2

A nonenhanced mass-like lesion (arrow), considered as hematoma, was seen in gallbladder after RFA. The hematoma was measured as 65.8 HU (Hounsfield units) in precontrast scan (A) and as 66.0 HU in portal-phase scan (B). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a heterogeneous echogenic mass in the gallbladder (C). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography showed a gallbladder with a localized filling defect (arrow) (D).

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

- Related articles

-

The management of post-transplantation recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma2022 January;28(1)

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Full text via PMC

Full text via PMC Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print